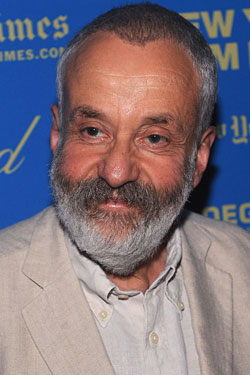

If New York cinema belongs to Martin Scorsese and Woody Allen, no other British filmmaker of the past 30 years has chronicled London quite like Mike Leigh (of Topsy-Turvy and Vera Drake fame), whose renowned, hands-on style entails months of improvisatory sessions to shape the narratives of his films. His irresistible latest work, Happy-Go-Lucky — which hits theaters tonight — is centered around Poppy (Sally Hawkins), a lovable singleton marked by an unsinkable optimism who offers up an endless stream of cheery rejoinders in response to life’s woes, much to the bemusement of those around her. Leigh spoke with Vulture about growing up in Manchester, the glory of Sally Hawkins, and why there’s big money to be made hawking drama in Japan.

Did the siren call of film come early for you?

I grew up in Manchester, and I was going to the pictures, as we called them, throughout the forties, and the 1950s, which were my teenage years, all that time. I couldn’t get enough of it, you know? There were fourteen theaters within walking distance of my house, without going into central Manchester, where the big cinemas were. Local fleapits, we called them. And every movie house would show two films on the program, the A-picture and the B-picture. But of course I never saw a film — until I was 17, and left for London — that wasn’t in English. It was all American Hollywood and British movies. I think the only film I saw that wasn’t in English was that puke-making French short Le Ballon Rouge. Awful! But I went to London to study acting and it was a mind-blowing experience because I discovered world cinema. There it all was.

You’ve worked with Sally Hawkins twice before. Did you have her in mind to play Poppy all along?

The plan was to put her at the center of this. Having worked with her before and seen her work, it seemed to me absolutely obvious that we should construct a film that put her at the center of things and exploit all her positive attributes.

You worked with everyone from old collaborators to acting neophytes on this film. What’s your casting process like?

On the whole, I cast the actors, not the parts, and then create the parts with the actor. There are exceptions to that. When we did Vera Drake, we knew that somebody had to be a judge and somebody had to be a doctor and a number of women were going to have to play characters who had abortions. But that doesn’t cast the character, that merely casts the function of the character. You just create the character with the actor. Indeed, when we did Topsy-Turvy, I started with the premise of Jim Broadbent playing W.S. Gilbert, and we then had to find an actor who could play Arthur Sullivan, who had to look like him, be a good actor, but also be a consummate musician. And in the end we got the only right answer — Allan Corduner fulfills all of those [roles]. With Happy-Go-Lucky, I got Poppy on the go and was then sauced to work with Eddie Marsan. The whole thing is a long investigation — that’s the glory, the discovery.

A lot of young filmmakers today seem driven by a more visceral style — out to make an impression more visually than humanistically, which stands in stark contrast to a lot of your work. How does that mode of filmmaking strike you?

It’s an inevitable result of people growing up in a world which is no longer literary, and which is visceral — the fact that kids have grown up with video games or whatever. Culture doesn’t stand still, and everything has happened organically for a reason. I don’t think — I know, in fact, that it’s simply not the case that no young filmmakers are interested in making films about real things or people. That’s there too. But the existence of the type of cinema you talk about is absolutely legitimate. So I embrace it, even it doesn’t necessarily mean I like it. But there are all kinds of movies about people in relationships that I can’t stand. It all depends on how it’s made.

Have you noticed any differences in the way that your films play internationally?

Obviously there are going to be nuances that don’t come across, even here. But these are details. We were apprehensive as to how Secrets & Lies would play in Japan, because it’s a white woman who has a black child. That’s not a comfortable thing in a Japanese context. So I went to Japan and talked to a journalist who said, “They’re going to love it, this is a very Japanese story because it’s about secrets and lies, and that’s what Japanese families are all about!” And it did big-time business in Japan. So they travel, and I think it’s because while the specific milieu is England, what I deal with — without being pompous or pretentious or presumptuous about it — are universal subjects.