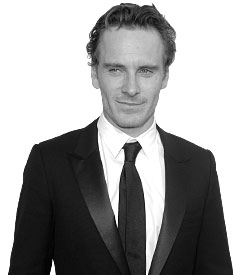

It’s safe to say that Michael Fassbender has had a pretty good couple of years. In 2008, the Irish-German actor commanded the screen in Steve McQueen’s controversial prison drama Hunger, for which he lost some unspeakable amount of weight to play an IRA prisoner on a hunger strike. Then, he showed up in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds as a British agent/film buff posing as a Nazi officer, a part that required him to play a dry, stiff-upper-lip Brit and speak fluent German. And now he can be seen in Andrea Arnold’s touching working-class drama, Fish Tank (a cause célèbre at the same Cannes Film Festival that Basterds premiered at last year), as the charming and seemingly kind boyfriend of the troubled heroine’s mom. All three roles are remarkably different, but Fassbender brings his unforgettable, palpable presence to all of them. He met with us in Soho during a recent trip to New York.

Your character in Fish Tank does some pretty awful things, and yet the film depicts him very even-handedly. He’s a charming guy, and he remains likable even after we learn all these bad things about him.

Connor is charming. He does a lot of positive things. He’s the only one who tells Mia that she has a talent, that she is special and should follow her dreams. She’s not getting that at home. She needs someone to teach her to have some self-esteem, and he does that. He does care for her, outside of a sexual nature. He finds her an interesting person. She’s a fighter. That’s what attracts him to her at first. The fact that the film doesn’t judge Connor was what made me want to work with Andrea. Having seen [her first feature] Red Road — that’s what I like about her characters, they’re ambiguous, she doesn’t make it easy for an audience by saying: “This is your hero, and this is your villain.” She brings these characters to life onscreen in a really non-judgmental way.

Was that balance something you had to work on a lot?

I just kind of knew, from talking to Andrea, what she wanted. After a while, you get a sense of the director. I didn’t have a script. None of the actors had a full script: Every Friday, we would get the following week’s work, and we did it in chronological order. I thought, she must be doing that because she doesn’t want me to preload this character, knowing what’s going to come later. So I decided to keep him fairly charming, fairly light. The character is a lot like me in some ways. Andrea casts pretty close to the personality she thinks she’s portraying. And the character’s actions will decipher the kind of person that they are. So I just tried to respond to what was going on and to allow things to take place.

Like Bobby Sands, your character in Hunger, this is also a very physical role. Are you drawn to those kinds of parts?

Every role requires physicality in a way. Even with Inglourious Basterds — I studied George Sanders and how he carried himself, the elegance and preciseness of his demeanor. I tried to embody that whole time period in the bearing of that character. But yes, physicality is very important to me. In theater, you’re used to working from the feet up, but in a lot of TV and film you become just head and shoulders. I like to start from the ground up. And I knew Andrea wanted Connor to have a very sexual presence. He comes into this female-dominated world, and I knew that his presence had to be sexually potent.

So, after what you had to go through in Hunger, losing a ton of weight and playing a character who is constantly beaten and humiliated, does every subsequent role seem like a piece of cake?

No. I get nervous and I worry before every film. I thoroughly enjoyed making Hunger. The subject matter was intense, so people always ask me about how difficult it must have been. But we had a lot of fun, actually. The scary part about Hunger that we all worried about was the long conversation with the priest, when they’re just sitting there talking: We felt if we got that right, then the rest of the film was in good stead.

The scene with the priest in Hunger is an incredibly long scene of people sitting at a table talking — much like the tavern scene in Inglourious Basterds. And both scenes are riveting. How do you make something like that work?

A good director. [Laughs] I think the secret is very simple, and we talked about this a lot on Hunger: It’s to not perform. To actually just listen to what the other person is saying. Once you do that, then the whole thing sort of falls into place. But if you’re just sitting there worrying, “Holy shit, what do I say next, when do I say it?” and so on, that’s a problem. When you’re doing really heavy dialogue-based stuff, you have to find a way to relax and to just listen and respond.

Quentin was very precise, and he knew what he wanted from that scene, and we spent two-and-a-half weeks doing it. He comes from a film background, but he does long takes, and he likes you to breathe in the scene. There’s a theater element to it. You’re not just doing one page of dialogue and then cutting. You’re prepared to do four, five, six pages at a time. And it doesn’t even need to have any dialogue. I always think of Stanley Tucci’s Big Night. I love that closing scene in the film, that long take of them in the kitchen making the omelette. No one says a word. What a beautiful scene.

Speaking of Tarantino, is it true you once directed and performed Reservoir Dogs onstage?

We used Quentin’s script. I was 18. I played Mr. Pink. We started off filming it in the locker room of our gym at school, and then I thought, Wait, this is perfect for stage. It mostly takes place in a warehouse. It was quite tricky, because at the time it was still a fairly controversial film. We gave the money to charity. I told Quentin about it when I went in for the audition, and I said, “Don’t worry, we didn’t make a profit off it!” But that was actually something I’m very proud of. It taught me an important lesson early on: As long as you have enthusiasm and passion, naïveté will get you very far. I didn’t know what I was doing, and we just sort of learned as we went along.

Your character in Inglourious Basterds is thoroughly fluent in German and English, much like you are. It seems almost like it was written with you in mind.

I don’t know who Quentin originally thought of for the part, or if he did. Obviously it was a massive help that I could speak German. But I did have to do a lot of work on it. I had a fantastic voice coach, Lena Lessing. She would work it through with me. The most important thing was that I didn’t stand out to a German speaker as an English or Irishman speaking German.

At the same time, your accent becomes a whole plot point in the film — more the fact that you don’t have any kind of accent, really. It’s almost like a BBC English version of German that you’re speaking.

Yes. I’m speaking something called Hochdeutsch [High German]. I knew that if I could get it as close as I could to neutral, it would work. I thought maybe I could make the timing or phrasing a bit different, which kind of jars. But then I did throw in some other things, I rolled my R’s a bit, that sort of thing.

So you’ve now appeared back-to-back in three films by three very distinct auteurs: Tarantino, Andrea Arnold, and Steve McQueen. How would you briefly compare their approaches?

I can tell you what’s similar about them. They’re wildly different personalities, but they all have a very good understanding of rhythm. The sound of the lines delivered is just as important to them as the visuals. And also the music and soundtrack are very important to them. They’re all very passionate about their work — “perfectionists” would be a good word to describe them. They all love working with actors, and they all create a special environment where you can take risks. I found with all of them that after you get to know them a while, you just get into a rhythm. It’s almost like telepathy. They don’t give you a lot of notes.