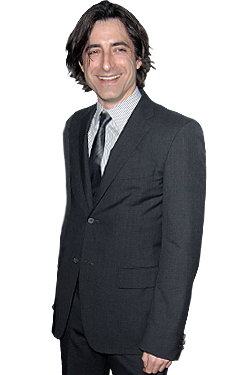

Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg, which opened last weekend, is an in-depth psychological portrait of a New York man (played by Ben Stiller) in disarray in Los Angeles. Baumbach recently took the time to talk to us from his home in L.A. about relating to his protagonist, American fiction, and why he still considers himself a New Yorker.

Have you ever felt like Greenberg?

Definitely! At points in my life, I felt more like him. Everyone I know, myself included, deals with this conflict between who you think you are — how you’d like to be seen, and the kind of person you want to be — and then how you may actually be in the world. I know people who are incredibly successful who still dress the way they did when they were 18, just because they still think that’s how they look good. There’s a great quote by Timothy Leary, that everyone’s favorite music is the music that was playing when they lost their virginity. We all have these notions of cool that come about at different points in our lives, and it’s interesting in how it evolves or doesn’t evolve in different people. It’s a bigger struggle and a more painful struggle and a funnier struggle for Greenberg, because it’s so all-encompassing for him.

But the film is pretty depressing, don’t you think? Did you feel depressed making it? You can tell us.

No, not at all. I had the best time of all on set making this one! I see the movie as hopeful. I understand what you’re saying. I’m interested in a cinematic world where the pain and humor exist simultaneously, though, rather than, I suppose, a comedy that takes a “time out” to have a “serious moment.” You can laugh or cringe or slowly sink into a quiet depression, all at the same moment. I’m always interested, when I see my movies with audiences, at seeing people laughing at times I didn’t anticipate. And then there are times that I think are really funny … where nobody’s laughing.

An older man with deep personal dissatisfaction who hooks up with a girl in her 20s is, one could argue, not the most revolutionary of concepts. What makes this film different from that standard trope?

He’s 40. He turns 41 in the movie, but he’s dealing with old wounds and hurts that came from when he was in his 20s. It made sense to me that he would be both attracted and also repelled by someone who was the age he was when he felt good about himself. I didn’t think so much about the age thing in any kind of genre -specific way. These two specific characters, it made sense to me that they would develop this start-and-stop relationship.

Your filmmaking has always had a very literary edge. Who are your favorite fiction writers?

Well, for this film, I’d have to say distinctly American stories about men at crisis points in their lives. I love Philip Roth, and he’s gone at this in a lot of ways over the years. There’s also John Updike’s Rabbit stories, Saul Bellow’s Herzog. I think what happens is that when you try to adapt those books into movies, they lose something, because they are so specifically written as novels. So I felt it was possible to do my own version of those ideas, but as a movie. I mean, I read all the time. Sometimes I get asked if I’ve thought about writing a novel.

Would you?

Well, it’s possible, but I really don’t think in terms of novels. I think in terms of movies.

Could you talk a little about the vision of L.A. that you present in this film? Would you call yourself an Angeleno now?

[Laughs.] No, I wouldn’t go that far. But I do have a place here and I’m here more than I used to be. I find I like having both, New York and L.A. Jennifer, my wife, grew up here, and I really wanted to document my experience of the city in a fiction. With The Squid and the Whale, I grew up in Brooklyn, had a very long history with that place, and used my personal connection to the city as part of this narrative. That was something I wanted to do again with L.A. in this movie.

And now you can drive?

As of a few weeks ago, yes.

The character is named Greenberg. Is there anything important about him being at least nominally Jewish?

He makes the distinction that he’s ‘only half Jewish’ at one point in the movie. It’s yet another thing he can’t fully own. I think he’s so trapped in this nightmare that his life has become that he has trouble owning everything. That’s why he says he’s doing nothing, it’s a way to beg off owning up to anything. His Judaism is another example of that.