IÔÇÖm not positive, but IÔÇÖm pretty sure that a naked dangling penis brushed lightly against me Tuesday night. This has never happened to me before, at least not at a Museum of Modern Art opening. Two nude figures, a man and a woman, face inward on either side of the narrow main entrance to the museumÔÇÖs newest exhibit, and unless you choose one of the other entries to the show (provided for the underage, uninterested, or queasy), youÔÇÖre electing to run the gamut of flesh. So I did. Just as I was thinking ÔÇ£Whew! Made it!ÔÇØ I felt something sort of slide and bounce a bit against my thigh.

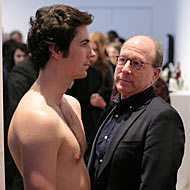

Welcome to ÔÇ£The Artist Is Present,ÔÇØ the first full-on retrospective of the hard-core Yugoslavian-born performance and body artist Marina Abramovic. While IÔÇÖve often found AbramovicÔÇÖs work hokey, melodramatic, and relentlessly narcissistic, thereÔÇÖs no denying that this survey of more than four decades of AbramovicÔÇÖs work is challenging and will generate outrage (most likely), amazement (possibly), and huge crowds (reliably).

For one thing, thereÔÇÖs a lot of live public nudity. I donÔÇÖt remember seeing this many breasts in a museum gallery since the last retrospective of the nineteenth-century French academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and those were on canvas. After passing between the two gatekeepers, youÔÇÖll see two people clad in black who look at and point their fingers at one another, and then two figures with their hair braided together as they sit in a large display case. A naked woman lies on a wall shelf with a skeleton resting on top of her. Then thereÔÇÖs Luminosity. Originally performed in 1997, this optically confrontational work consists of a completely unclothed woman, her arms stretched out, sitting spread-legged on a bicycle seat mounted high on the wall.

Abramovic has always dealt in shock and endurance, punishing the body, pushing viewers out of their comfort zones. In the past, she has posed with an arrow drawn in a bow and pointed directly at her heart, and swapped lives with an Amsterdam prostitute for four hours. This early work can still set your nerves and ideas about art on edge.

At MoMA she is attempting to go the limit, and also to reproduce literally the metaphysical interchange between artists and viewers. For the 700 hours of the exhibition, Abramovic will sit in the middle of MoMAÔÇÖs atrium, at a table. You can sit across from her. There you will stare at her while she silently stares back. After just two hours on opening night, Abramovic looked exhausted, drained, destroyed. Viewers cried, ran away, or looked sick. ItÔÇÖs almost unbelievable that after all the shock and button-pushing going on upstairs, just sitting silently and staring seemed to be the most impossible act of all. Abramovic gets you to understand why many animals hate being looked at by humans. ThereÔÇÖs something powerful and uncanny and pure about an unbroken gaze.

Whether you like this exhibition, laugh at it, or think of it as a freak-show clich├®, thereÔÇÖs little doubt that Abramovic is opening up MoMA, injecting it with life, altering its boring course in ways that the previous dreary Gabriel Orozco show, for example, never did. I may not be an Abramovic convert yet, but IÔÇÖll take this show as a step in a direction away from yet another roundup of the usual male post-minimalist snooze fest. Oh, and when you walk into her show, I wonder if youÔÇÖll go around the two nudes, which one will you face, how fast youÔÇÖll go through, whether youÔÇÖll stop to look at one, or if anything will brush against you.