Note: Scott Brown, New York’s theater critic, was unavailable to review this show.

Walk into the Jacobs Theater, and Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson envelops you long before you sit down. Red Christmas lights and twinkly chandeliers are strung every which way over the orchestra seats, the columns are wrapped in pelts and rawhide laces, and there’s scraggly-looking taxidermy hanging from every available surface. You can barely see the stage, which is low; the blood-red seats almost blend right into the footlights. It’s a spectacular first impression. Donyale Werle, the scenic designer, has a lot to be proud of, and ought to have a Tony on the mantel next year.

And then the show starts. “You ready?” Benjamin Walker, as Andrew Jackson, bellows to the audience, indie-rock-show-style. “Are you ready?!” And with that, the sense that you’re going to be brought in, drawn in, made emotionally one with the material — all of it evaporates. The set may be wide open, but dialogue is so laden with ironic distance that the proscenium practically looms back into view, pushing back the audience.

Every character onstage, from power-hungry Jackson to flighty Martin Van Buren to dopey John Quincy Adams, delivers deliberately dumb lines in deliberately clueless tones, like a bunch of 25-year-old Williamsburghers, arching their eyebrows so we know that they know they’re idiots. (Lucas Near-Verbrugghe, in particular, plays Van Buren uncannily like Absolutely Fabulous’s Edina Monsoon.) There’s even a Cher moment, complete with disco ball, inserted strictly for an easy pop-culture laugh. The tone is set by the show’s present-day narrator, a frump in a teddy-bear sweater and dorky glasses who arrives on one of those motorized wheelchairs with a flag strapped to the back. She is meant to stand for the stodgy correctness of schoolroom history, and might have been a convenient way to provide the timeline to the audience. But she ends up simply becoming fodder for easy, superior titters.

The story, by Alex Timbers (of the troupe Les Freres Corbusier) and Michael Friedman (who wrote the music and lyrics for Saved!), begins with Andrew Jackson’s tough Tennessee upbringing, and, as directed by Timbers, Walker plays him like a minor character in a Kevin Smith movie — an anomic suburbanite, driven to power because he was tired of hanging around the frontier ‘s 7-Eleven. “Life sucks,” Walker sings, “and my life sucks in particular.” Before long, though, he’s bellowing: “Who am I? I’m Andrew fucking Jackson!” (The word “fuck” should be listed as an additional character here. Remember when your parents used to say that cursing was the refuge of people with limited vocabularies? They were onto something.)

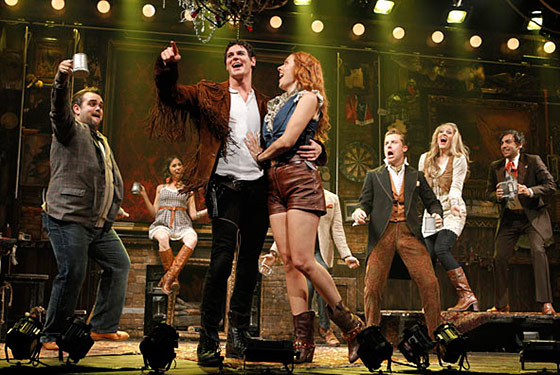

Timbers and Friedman have, admittedly, set themselves a tough goal. They aim to write about populism and the monstrosity of all-American genocide, and make their point not just with humor but with the highly colloquial, we-know-all-about-theatrical-conventions-and-therefore-violate-them manner of the Upright Citizens Brigade Theater. The first half-hour, in fact, might’ve been the best UCB show you ever saw, run amok — a fast-moving Harold improv scene that just keeps going. The creators are aided by a lot of superior (and good-looking) talent onstage, especially the super-tight band (which participates in the action) and the super-tight-panted Walker. As Jackson, he has a serious voice and a big, athletic stage presence. But he’s directed to take his character all over the place: now powerful, now whiny and ineffectual, here clownish, there vicious. We never quite get what he is.

As the story develops, the allusions to contemporary politics get more and more explicit. “Take a stand / Against the elite,” a cowgirl character sings, and Jackson’s sympathies with the frontier and irritation at the government and banks back East escalate. Timbers and Friedman grasp that populism cuts both ways, and that getting elected takes a very different skill set from actually governing. Wisely, they are just as willing to take pokes at Obama as at Palin and Bush — even if they’re fairly obvious. (As is one “dabble in witchcraft” gag, but at least it’s fun and fresh.)

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson is 90 minutes long, and around minute 70, I began to despair of it. I started to wonder: Surely the whole play couldn’t be about just that — facile, glib language mirroring a facile, racist political movement. Or maybe it was simply suffering from the move to Broadway, another show that originated in a small space dying in a big house. (A friend who saw Bloody, Bloody at the Public told me the next day that the humor had become broader and shtickier, and the music less powerful.) But then, finally, mercifully, something grabbed hold. The moment comes when the playwrights finally address what they care about in this tale: the Trail of Tears, the genocidal murder of tens of thousands of Native Americans. Suddenly they cannot fail to be genuine, and while they don’t snap into full solemnity, much of the aw-screw-it dialogue drops by the wayside. Finally, the show escaped across the footlights, out into the real world. It was an intense fifteen minutes that hinted at how powerful the show could be. If only it had come an hour earlier.