Sometimes, there’s nothing more dangerous than a little old-fashioned entertainment—and entertainment doesn’t come much more old-fashioned than the minstrel show, American theater’s most peculiar institution. In their final collaboration, The Scottsboro Boys, John Kander and the late Fred Ebb make a risky wager: using minstrelsy to tell a foundational parable of the civil-rights movement. The titular Boys were nine black youths falsely accused of rape in Depression-era Alabama—then falsely convicted, over and over again.

It’s a story of brazen injustice, and the show’s theatrical provocations are proportionately broad and basic. “Everyone’s a minstrel tonight!” the boys belt in the opening number, setting the subtlety thermostat somewhere between Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret and Glee. And yet the point-blank theatrical force of the show cannot be denied: The talent onstage is so lavish it overwhelms our comfortable pieties with pure showmanship, conjuring your applause in waves, then quietly placing an asterisk after each bravura number: Did I just clap for … a shuck-and-jive?

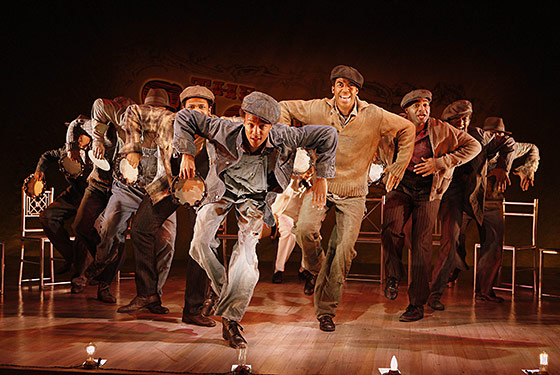

Director and choreographer Susan Stroman puts nothing between you and her ensemble, a peerless collection of triple threats who execute her airborne hoofery with grace and violence. The set is just chairs and a plank or two, and minstrel convention is respected in minute detail, from the cakewalk to the “end men” (the unambiguously crazed duo of Colman Domingo and Forrest McClendon)—and, of course, the Interlocutor (John Cullum), the (white) straight-man emcee. (The mandatory star applause that Cullum receives, as he promenades onstage resplendent in Colonel Sanders white, is marvelously uncomfortable in this context—Stroman’s tart little joke on an irritating trend among starstruck, self-congratulatory Broadway audiences: Yes! By all means! Clap for Massah! Because you recognize him!)

The boys themselves tap into the demonic power of pure performance, milking each minstrel tradition (the Jim Crow shuffle, the emasculating drag number) for its essential performative energy, constantly daring us to separate the zazz on offer from the moral matter at hand. As Haywood Patterson, the most fiercely principled of the nine, Joshua Henry (American Idiot) does the near impossible: He takes that unluckiest of suicide missions, the earnest angry-young-man role, and brands it onto the back wall of your brain. In “Nothin,” a searing shuck-and-jive number that approaches the tuneful discomfort zone of classic Cabaret-era Kander and Ebb, Patterson focuses rage into meter, choreographed by Stroman at a perfectly, excruciatingly slow tempo. Among other standouts: Christian Dante White takes a drag role to the razor’s edge of misogyny, then walks it back at an accusing amble; and young Jeremy Gumbs’ startlingly pellucid voice recalls a pubescent Michael Jackson.

Still, Assassins this ain’t. (The loss of Ebb is felt keenly in some of the lyrics: Yes, society rhymes with notoriety, but surely that shouldn’t be the high point of a show’s prosody?) The nine remain an amalgam, and attempts to distinguish individual characters inevitably founder on the rocks of minstrelsy: Kitsch subverts content somewhat, not (as the creators

clearly believe) the other way around. But then, maybe that’s the most subversive message of all. The Scottsboro Boys isn’t a precision-guided social endoscopy: It’s a single, stunning blow to the temple. And on its own discomfiting, blunt-force terms, it’s utterly successful.