You have to hand it to Damian Chazelle for attempting, fresh out of college, to make something like Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench. It’s an awfully peculiar hybrid, part semi-improvised mumblecore slice-of-life, part lush, MGM-style song-and-dance musical with a touch of the French New Wave. When it works (about half the time), it catches you off guard: You go, in an instant, from exasperation to exhilaration.

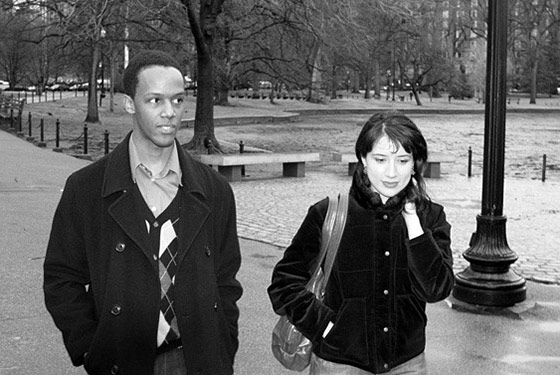

The narrative is glancing, a series of amorphous interludes. Trumpet-player Guy (Jason Palmer) and his girlfriend, Madeline (Desiree Garcia), sit in silence on a park bench, having apparently broken up. In random scenes, we catch the pair with each other (in flashback) as well as a cross-section of musicians, bohemians, and twentyish Bostonians eking out a living as bike messengers, dishwashers, or waitresses. Standing around at a party, they launch, with little preamble, into a finger-snapping jazz piece with an old-fashioned tap dance, then return to their meandering flirtations, their inconclusive quasi-relationships.

The tension between those half-formed dialogues and the stylized musical numbers would work better if the scenes were a tad more shaped, if the actors revealed more, if the hand-held camera didn’t seem as purposeless as the characters. But it’s a good try—a stab at throwing this often-maddening new genre and its terminally indecisive denizens into relief, the way Dennis Potter created a dialectic out of abrasive realism and stylized pipe dreams.

The music does much to fill the holes. The score is by Justin Hurwitz (with one song by Daniel DiMaggio), and the melodies—in both the songs and the lyrical orchestral sections—are so easy and infectious you’d swear they were classics. (The Bratislava Symphony Orchestra plays with brio.) The showstopper comes near the end, a fluid, gorgeously choreographed diner number where busboys dance with their mops and waitresses tap on counters and the camera hurtles along with the exuberantly charming Garcia as she leaps off stools and twirls among the fryers. (Kelly Kaleta staged the dances.) Chazelle ends on a brave note, an attempt to bridge the disparate styles. Guy, on the verge of losing Madeline forever, plays a long, plaintive, increasingly desperate and discordant trumpet solo. Like the movie itself, it’s using raw, limited resources to reach for the stars.