Danny Boyle is modern cinema’s most virtuosic whore. I do not mean that to sound quite as unflattering as it does. Cinema is a swell medium for whores, and there’s a touch of whorishness in some (but not all) of our greatest directors. Knowing when to deliver pleasure and when to flash, tease, and strategically withhold is an art. The only problem with directors who are primarily whores is that they give us nothing to take home apart from the dwindling memory of sensations: say, jump cuts of a handsome young man running from a sociopathic drug dealer, a low-angle view of a drop of infected zombie blood falling into a father’s eye, and a music video of young people dancing joyously on a train platform.

Now, in 127 Hours, Boyle gives us a music-video-style exercise in boundless freedom, cruel confinement, and crippling/liberating self-mutilation that makes for just about the ultimate trick.

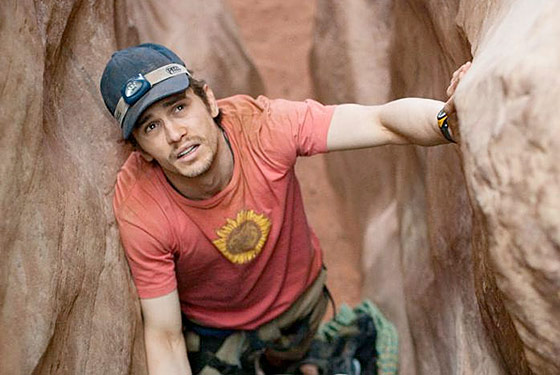

The film is based on Aron Ralston’s memoir Between a Rock and a Hard Place, which tells the story of how he was pinned under a boulder while hiking in an isolated “slot” canyon (i.e., one that is narrower than it is wide) in Utah — and how, after 127 grueling hours with no hope of rescue, he was forced to cut off his own arm with a crude blade. That’s not a spoiler: The come-on for the picture is, in essence, “See James Franco cut off his arm!” Here’s how I got off a prescreening cell-phone call with a friend: “Okay, time to watch James Franco cut off his arm.” “Oh, that movie.” “Yeah … here goes.” “Have fun.” “I won’t.” [Pause.] “I’m going to close my eyes.” “I hear there’s sound, too.” “Oh, hell … ”

The act turns out to be presented as a garish spectacle, a test of our endurance akin to the character’s. And it’s preceded by multiple teases: I counted three false starts, moments when Franco’s Aron gazes at his arm (turning black from lack of circulation and clearly doomed anyway), and I thought, “Here we go.” When the scene finally comes, I opted to watch it in Finger Vision, through a web of digits that opened and closed. It’s a long four minutes or so, and sometimes I looked at the faces of colleagues instead of the screen. The guy next to me had his head under the seat at the ten-second mark, but critic Thelma Adams did admirably, only violently recoil in the last fifteen seconds. You’ll be pleased to know that the sound of muscle being cut is quite different from the sound of flesh and tendon. Do I hear a Sound Oscar?

Anticipating that he’ll be stuck in a crevice with his leading man, Boyle opens with a barrage of random people in motion, with multiple split screens and pictures-in-pictures (PIP), and Franco bounces around more than Donald O’Connor in Singin’ in the Rain. He’s practically climbing the walls until he hits the Utah canyons, with Boyle’s camera swooping over the mighty cliffs. Boyle used two primary cinematographers, Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak, and the look is akin to turning the “vividness” setting on one’s high-def TV up to “11.” The deep-focus imagery is ravishing, and when Aron hooks up with two female hikers (Amber Tamblyn and Kate Mara) and plunges with them into a swimming hole in a giant cave, the girls’ explosion of feeling is contagious. Aron is so hyped-up that he tests the boulder that will ultimately fall on his arm before he steps on it — you could come away thinking it gave way under the pressure of his and Boyle’s hammy verve.

I should have predicted that, once his protagonist is wedged in, Boyle would opt to evoke Aron’s mental landscape — anything to change lenses, go back and forth between color and black and white, get the hell out of that slot. Aron had a video camera with him (he actually taped good-byes to his parents), which gives Boyle an honest way to add more PIP (and Franco a way to talk to someone other than himself). But Boyle also serves up showy visions and dreams, as well as flashbacks of Aron’s ex-girlfriend. Pop music, some of it ironic (“Lovely Day”), floods out from the screen. The only sustained stretch of real time is, you guessed it, the arm-severing — although there might be some abstract imagery in there. You’ll have to ask Thelma.

127 Hours is a “wow movie” — it leaves you jittery, a little crazed. But I kept flashing back to a much older film, Roy Ward Baker’s 1953 Inferno, which recently screened at the Film Forum in glorious 3-D. Robert Ryan plays a rich jerk set up by his wife and her lover, who leave him on a ledge in the desert with a broken leg. Although there are cutaways to the lovers, much of the film consists of Ryan trying to slide down a hill and cope with sundry physical (3-D) obstacles. The film’s self-containment is enthralling, and the pleasure it gave me will linger far longer than anything in 127 Hours. Well, the sound of muscle being cut — ;that will probably linger. Like tinnitus.