My nominee for Best Picture of the year ÔÇö maybe the best picture ever, because itÔÇÖs essentially made up of and is an ecstatic love letter to all other movies ÔÇö is Christian MarclayÔÇÖs endlessly enticing must-see masterpiece The Clock. This elliptically simple, spectacularly dazzling 24-hour film is made up of thousands of scenes and snippets from films, all marking the passage of time, minute by minute, sometimes second by second, on clocks and sundials and people speaking the time and, in one case, a child drawing a timepiece on his arm. ItÔÇÖs all synchronized so that whatever time it is onscreen is the actual time in New York, and it has played to packed audiences at the Paula Cooper Gallery since January 21. A metaphysical tour de force of untethered meaning and involuting interlocking contrapuntal rhythms, The Clock is more than a movie or even a work of art. It is so strange and other-ish that it becomes a stream-of-consciousness algorithm unto itself ÔÇö something almost inhuman.

The dark gallery is filled with a dozen couches. ItÔÇÖs almost always packed with people sitting, crouched along walls, or standing in the back. Slow-moving lines often snaked outside. I never saw anyone cut ahead ÔÇö something about the integrity of the Paula Cooper Gallery or the film itself brought manners to the hierarchical and impatient art world. I stood next to bigwig curators, famous artists, a Russian super-collector, a movie star, and one well-known movie director who later told me that she was thrilled to see a bit of her film included in The Clock. The only misbehavior I heard about was an unconfirmed rumor that a major megadealer was demanding privileged access for his clients.

I got in six times and failed on another three tries (the line too long, the weather too cold). In all, I saw nineteen hours of The Clock ÔÇö every minute from 6:50 a.m. to 1:23 a.m. It makes sense that IÔÇÖve never seen the sequences from 1:24 to 6:49 a.m., since that stretch is pretty much a blank in my life anyway. On my first viewings, I was simply flabbergasted at the fact that someone had had the squirrely perspicacity to do this ÔÇö the endless hours of preparatory research that went into this gigantic thing constitute the ever-present invisible content of The Clock. Then it gradually dawned on me: There are so many film scenes about time that there are probably many possible versions of The Clock ÔÇö all different, just as some scientists say there are simultaneously parallel realities.

By the last time I left The Clock, at 10:05 a.m. on a Sunday morning ÔÇö having just seen the jarring sight of one of my employers, Sarah Jessica Parker, marrying ÔÇ£Mr. BigÔÇØ in Sex in the City ÔÇö the film no longer seemed to mirror the world. Instead, I had the uncanny sense that life was mirroring the movie. Everything going on around me on my way home seemed suddenly inseparable from the rhythms of time. Every action I saw that Sunday morning ÔÇö every dog walker, jogger, person hurrying to breakfast, coming out a subway, or going to church ÔÇö seemed less individualistic and more entangled in a built-in, beyond-our-control, deeply cosmic structure.

I thought of Walt Whitman, who wrote of being ÔÇ£a phantom curiously floating.ÔÇØ That was me ÔÇö nomadic, drifting in this atmospheric flow, part of something but hovering above it, disembodied, witnessing. In the spirit of Whitman, then, hereÔÇÖs a piecemeal fragmentary diary of what I saw over six hours ÔÇö roughly one-quarter ÔÇö of The Clock.

At 6:50 a.m., my wife and I walk into the half-full Paula Cooper Gallery. I see couples canoodling on couches, a few people asleep, and scattered junk on the floor: beer cans, popcorn, candy wrappers, a few bourbon bottles. Someone nearby is snoring. It reminds me of Chelsea in the days when sex mattered more than the art business. The room smells musty. The first scene I see is a yummy, randy moment of Charles Aznavour waking up and spanking a lover in bed. Soon more lovers begin waking up. Michael Caine puts his wedding ring back on. Men and women are sleeping alone, creeping secretly back home, carrying clothes, ducking into doorways, their clothing strewn on floors. Shelley Winters snores in Lolita, and I feel Humbert HumbertÔÇÖs revulsion. Darkness begins turning to light, both onscreen and outside. I hear birds chirping, see scenes of empty office buildings and quiet cafeterias. Joggers start appearing; people fetch papers and milk bottles from stoops.

At 7 a.m., Marty McFlyÔÇÖs Rube Goldbergian alarm clock goes off. Suddenly people in scene after scene are awakening to alarms, hearing radios, throwing clocks across rooms, rolling over back to sleep. Marlon Brando puts on cold cream; Willem Dafoe already looks haunted. The young Paul Newman curls up. I hear bells and watched people peeping into their new loversÔÇÖ medicine cabinets. At 7:09 a.m., Brando again, staggeringly bloodied and battered, victoriously goes to work at the end of On the Waterfront. Just then, James Bond looks over Pussy Galore; Johnny Cash stakes out a suburban home; a woman and man have morning sex. People soon start catching trains and buses. Coffee rituals begin ÔÇö scooping beans, boiling water, adding sugar ÔÇö all over dozens of movies, every single one with a clock in the background. A woman turns from a lover and puts on her bra.

At 7:23 a.m., Tom Hanks, in The Terminal, shaves in an airport bathroom as another man asks, ÔÇ£Ever feel like youÔÇÖre living in an airport?ÔÇØ. Prisoners start going into prison yards; convicts plan breakouts; someone waits on death row; a woman prepares to go to the gas chamber. At 7:30 a.m. Michael Douglas gets home to a phone message in Fatal Attraction& (itÔÇÖs Glenn Close who tells him sheÔÇÖll ÔÇ£call back soonÔÇØ). Tracy and Hepburn wake up and have breakfast in bed. ThereÔÇÖs tooth-brushing, vitamin-taking, curtain-opening. Single dads pack kids off to school, and when the children ask, ÔÇ£WhereÔÇÖs mommy?ÔÇØ the fathers go silent. At 7:48 a.m. a woman says she wants to have ÔÇ£twelve-second sex.ÔÇØ A few minutes later, Woody Allen wakes up with Diane Keaton and says, ÔÇ£I have not slept that long in ages. What time is it?ÔÇØ She says, ÔÇ£7:58 a.m.ÔÇØ

At 8 a.m., more alarms go off; more scenes of the gas chamber; a man says to a woman, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs 8:05 a.m. IÔÇÖm going to fuck you by 10 a.m.ÔÇØ Then Robert Duvall, a.k.a. Lieutenant Kilgore in Apocalypse Now,looks at the carnage all around him, and says, ÔÇ£I love the smell of napalm in the morning.ÔÇØ YouÔÇÖve heard it a thousand times, but here, when the camera pulls back, you notice that his watch says 8:09 a.m. Alex, the ultraviolent protagonist of A Clockwork Orange, appears as heÔÇÖs awakened by his feckless mum ÔÇö and then we get John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson, covered in blood, having coffee as Quentin Tarantino lectures them about the potential peril of ÔÇ£a Bonnie situation.ÔÇØ At 8:20 a.m. John Candy and Steve Martin wake up in bed together; Candy kisses MartinÔÇÖs ear. Martin asks Candy where his hands are; Candy says, ÔÇ£Between two pillows.ÔÇØ Martin shrieks, ÔÇ£Those arenÔÇÖt pillows!ÔÇØ and they both leap out of bed in homosexual panic.

By 8:35 a.m., weÔÇÖre seeing traffic jams. At 9 a.m. we get a split second of Jack Woltz, The GodfatherÔÇÖs uncooperative Hollywood movie producer, just an instant before he realizes thereÔÇÖs a horseÔÇÖs head in his bed. Minutes later, at 9:11 a.m., Marclay gives us a shot of the first World Trade Center on fire on TV, and time seems to freeze. Soon we see kids in school taking tests, businessmen taking meetings, people punching time clocks. At 10 a.m., lines wait for Willy Wonka to open up the Chocolate Factory. This goes on and on. At 10:22 a.m., Molly Ringwald casts The Breakfast ClubÔÇÖs cute boy a glance. At 10:53 a.m., a funny moment: ItÔÇÖs a scene from an old Bible movie, and Marclay has noticed that the actor is wearing a wristwatch.

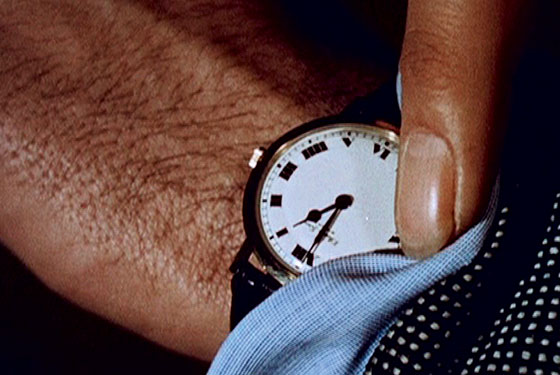

At 11:38 a.m. Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper sit atop their Harleys at the edge of the desert, as Fonda throws his watch away. Next Stan Laurel breaks a grandfather clock. At 11:45 a.m., we return to Pulp Fiction for one of the stranger scenes about time in any film: Christopher Walken, as Captain Koons, holds up a watch and tells a young boy, Five long years, he wore this watch up his ass  I hid this uncomfortable hunk of metal up my ass for two years  And now, little man, I give the watch to you.

Leonardo DiCaprio wins two tickets and scrambles aboard the Titanic. Then comes noon. Gunfighters walk in deserted towns; Gary Cooper waits for something to happen; Henry Fonda pulls his gun; Charles Bronson challenges outlaws. Suddenly we see Laurence Oliver as Hamlet, at noon in the graveyard delivering his ÔÇ£Alas poor YorickÔÇØ speech. A moment later, we see an incredible extended pathos-filled scene of Charles Laughton, wildly clinging to a clanging bell as Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Dustin Hoffman as Rain Man drones about the time: ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs 12:21. ItÔÇÖs definitely 12:31.ÔÇØ At 12:45 p.m. someone asks Harpo Marx what time it is and he pulls a huge clock out of his overcoat. At 1:05 p.m. the boy in The Tin Drum screams at the top of his lungs and breaks the face of a clock.

I could go on forever, but then again so does the film, because it covers the entire 24 hours. I finally left after a scene of two lovers having afternoon sex in which we see the woman looking at her watch as the man grinds away. (Maybe it made me nervous.) The Clock is up through Saturday, and I will be there for as much of the next two days as I can. So should you.