A bunker mentality pervades director David Cromer’s muffled new production of The House of Blue Leaves, and it’s not just because scenic artist Scott Pask’s grim vision of Vietnam-era Jackson Heights looks disturbingly like a duplex in Terror Era Kabul. This latest remount of John Guare’s satiric late-sixties philippic against the twin forces of fame and power — and the squalidly “aspirational” peasantry that both sustains and is sustained by those forces — feels strangely hunkered down in itself, even as geysers of absurdity (a trio of ravenous nuns, a gift-wrapped bomb intended for the visiting Pope) erupt willy-nilly in the dingy Queens living room of aspiring songwriter/discontented zookeeper Artie Shaughnessy (Ben Stiller). Like its principal characters, House feels, for all its determination, caged in its own dreamworld.

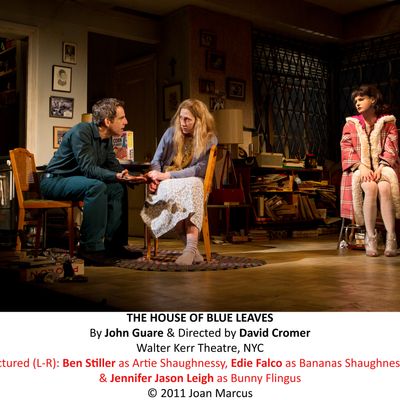

And yet, I can still feel House’s trio of boldfaced topliners — Stiller, Edie Falco, and Jennifer Jason Leigh — adjusting to each other’s unique dynamics. Stiller, with his angry hangdog sputter, is almost too perfect for Artie, a never-was who’s counting on his successful movie director pal Billy (Thomas Sadoski) to pluck him from obscurity and set him up in Tinsel Town as a hit songwriter and all-around showbiz potentate. Not that he’s waiting: After a long day at the zoo, Artie plummets from amateur night to amateur night, plinking out plaintive little Tin Pan Alley–style originals with titles like “Where’s the Devil in Evelyn?” (There’s no better shorthand for Pathetic than talentless, ingratiating ivory-tickler dying for you to hear his “originals.”) Nothing small will do for this smallest of men. “For my dreams,” he brags, “I need a passport and shots.” Stiller’s fiercely funny, but never more so than when he’s alone in a scene, at the piano, on the phone; he’s got incredible chemistry with himself. With others, there’s distance, daylight, and sometimes a little dead space.

Artie hopes to escape both his life and his wife, the mentally ill Bananas, played by a shambolic Falco: haunted, hollowed-out, and tragically funny as she spins heavily medicated monologues about her many humiliations at the hands of the powerful. (Her speech about a disastrous, spurned, and probably imaginary attempt to give Jackie Kennedy, LBJ, Bob Hope, and Cardinal Spellman a ride in her Buick still resonates with our indignant but no less starstruck era — especially her pathetic final question: “I know everything about them. Why can’t they love me?”) Bananas is bedridden — she recently “tried to slash my wrists with spoons” — and institutionalization (at the azure-foliaged facility of the play’s title) is in her future. Hovering in the wings is Artie’s ten-clawed climber of a mistress, the fierce Bunny Lingus (Leigh). (Guare, whatever your overall opinion of him, is one of the great moniker-makers of the postmodern stage.) The pair met when Artie “kind of raped her” in a health-club steam room, and since then, she’s been convinced of his indomitable drive, even as his lingering attachment to his invalid wife has her wondering. Leigh’s attack is strong, her timing hair-trigger, but she hurtles through her speeches with such force, her sustained energy sometimes feels like a drone note: Nuances get lost. (Everybody’s operating at slightly different tempos, and dialogue seems to pile up in some places while feeling scant in others.)

Into this already-bonkers world wanders a pushy klatch of starstruck nuns (Mary Beth Hurt, trailing novitiates Halley Feiffer and Susan Bennett) who are looking for tickets to see the visiting Pope. Also fixated on the papal visit is Artie’s and Bananas’ equally bananas son, Ronnie (Christopher Abbott, stepping into a role Stiller played on Broadway in 1986), who’s AWOL and hatching an assassination plot and fantasies of infamy. Also dropping in, to steal a scene or two: the superb Alison Pill, fox-furred and peroxided, to play Billy’s deaf starlet girlfriend; her bits are sheer vaudeville, and her startling exit befits a bombshell.

Cromer, true to form, wants to put us closer to the action. He knows Guare’s text intentionally maroons every character on his own island of entitlement and wish fulfillment, and you can feel him pulling people back into the room. (And what a room it is: Pask’s created a kind of lower-middle-class mud-dauber’s nest, plastered with drab paper waste and clutter — even the sky above is a mass of dirty plastic sheets.) But in restoring some room-temperature naturalism to Guare’s cavern of antic despair, he may have inadvertently cramped and muted his performers: Unless they’re addressing the audience, the actors feel a bit remote, shooting their lines upstage and offstage, occasionally struggling to push the mad energy past the proscenium arch. This is a furious play, a vicious and ungenerous play, and we should be made to feel that. I got it in gentle waves, but never in hurricane-force slaps. Perhaps it’s just the passage of time: House was written back when the grand promises of the Great Society and Vatican II were decaying even faster than the Star System of Old Hollywood, and no purposeful revolution could cohere or find secure footing. “When famous people go to sleep at night, it’s us they dream of, Artie,” chants Bunny, without rue or irony, in a kind of lullaby. “The famous ones, they’re the real people. We’re the creatures of their dreams.” A line like that ought to galvanize us, the passive patsies out in the gallery. Instead, I felt a gentle perplexity. Sometimes, sitting out there in the dark, watching these famous people mount a case for the violent, oppressive absurdity of fame, I felt like a creature of their dreams. And I wondered, Inception-like: Who needs to wake up? Me or them?