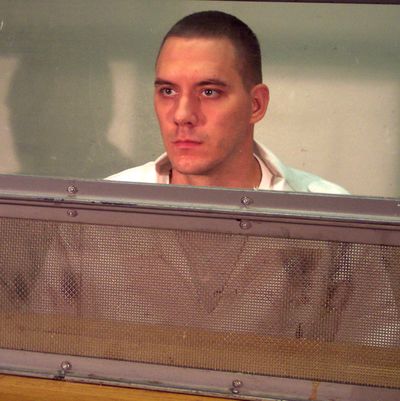

Did Werner Herzog know what he was getting into when he went down to Texas to interview prisoners on death row? In his latest documentary Into the Abyss, he has stumbled on a story more mysterious, absurd, and devastating than the one at the heart of Truman CapoteÔÇÖs In Cold Blood. Three people ÔÇö a mother, her son, and her sonÔÇÖs friend ÔÇö were murdered by teens in 2000, apparently over a red Camaro. The one scheduled for execution, 28-year-old Michael Perry, says heÔÇÖs innocent, and he looks so dopey and ingenuous, a ringer for Jim Carrey in Dumb and Dumber, that you want to believe him ÔÇö especially since the other man, Jason Aaron Burkett, who got only life imprisonment, is a handsome, fluent, and obvious sociopath. But when Herzog interviews BurkettÔÇÖs father, whoÔÇÖll die in prison, who pleaded with the jury not to take the life of a son ÔÇ£who had trash for a father,ÔÇØ itÔÇÖs hard to think about a miscarriage of justice.

So you think about the death penalty and how itÔÇÖs applied, horror layered on horror. A Death House chaplain stands before HerzogÔÇÖs camera and weeps at the sudden cessation of lives he witnesses weekly. A man, Fred Allen, talks of presiding over 125 executions, spending the day with the condemned man and helping strap him onto the gurney in fifteen endless, well-rehearsed seconds, holding down the left leg while someone else held down the right while someone else held the left hand and someone else the right and someone else stood by to hold down the chest if the subject tried to rise. He was finally broken by the execution of a woman, Carla Faye Tucker. ÔÇ£No sir,ÔÇØ says Fred Allen, through tears, ÔÇ£nobody has the right to take another life.ÔÇØ

I donÔÇÖt entirely agree. Unlike many of my liberal friends, I am not philosophically averse to the state killing people who are obviously guilty, although I cannot support the death penalty in practice, given how many innocent people are murdered by prosecutors and police via sham trials. In any case, no anti-death-penalty documentary has spent this much time with the victimsÔÇÖ families. They are front and center in Into the Abyss ÔÇö theyÔÇÖre in the abyss, too ÔÇö grieving for what will never be recovered. Footage from the crime scenes is unspeakably horrible. The mother was in the midst of baking cookies when shot down for a Camaro that now, a decade later, sits rusting in a police lot, a tree having grown up in the middle of it.

In prison, Burkett married a pretty young woman who wrote to him, works on his appeal, and is about to have his baby, a boy, thanks to sperm smuggled out of the prison. He will grow up, like his daddy, with a father behind bars. Herzog portrays not just a single injustice but a whole sick, tragic ecosystem of senseless crime and uncomprehending punishment. This is a remarkable film.