Writer writes about writing: Now, there’s a headline that generally trips my every mental spam filter. Few subjects register higher on my Tediumeter than the struggle of scribes, the agony of creation, the precarious balance of discipline and insanity, the rare thrill of — hey, look at me, trying to make it sound interesting! See, that’s what we do. We self-justify, we self-mythologize. (We have to. We spend a lot of time by ourselves.) All writers want to write about writing, for the same reason the media wants so desperately to cover itself. At least when Stephen King spins this sort of endoscopic yarn, he has courtesy to spill a little blood, as a sop.

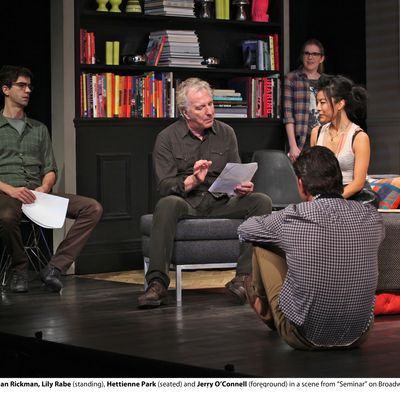

Nobody dies in Theresa Rebeck’s Seminar, and for approximately two thirds of this delightfully, effervescently empty play, we don’t even want anyone to. That’s a significant achievement, considering how intrinsically irritating all of these characters are and how vastly Rebeck’s interest in them outstrips our own, often by several orders of magnitude. We open in a one-panel New Yorker cartoon: a palatial rent-controlled apartment on the Upper West Side, packed with no-longer-young dilettantes. Poor little rich girl Kate (Lily Rabe), whose family owns the joint, is hosting a writing seminar for a klatch of friends, associates, and connected types, including her platonic longtime pal Martin (Hamish Linklater), a penniless, overeducated do-nothing with a cramped outer-borough apartment as badge and bona fide of his “authenticity.” Also aboard is Douglas (Jerry O’Connell), a poseur with a famous surname and connections aplenty, who mostly surfs between designer-label writers’ colonies, accruing cachet and pseudo-academic buzz phrases. Rounding out the quartet is the hot-to-trot climber Izzy (Hettienne Park), who’s post-feminizing her way to the top of a still mostly male publishing establishment. Into these wobbly pins crashes the instructor, Leonard (Alan Rickman), a once-celebrated, now-embittered novelist who makes a living brutalizing aspiring authors with something he calls “the truth.”

For Leonard, who’s from the Hugh Laurie and Simon Cowell school of Merry Olde Contempt, humiliation is performance art and teaching tool. He scans the first page of a short story Kate’s been working on for the better part of a decade and then stops, pronouncing it, in deliciously bituminous tones, “relentlessly talent-free” and not worth another minute of his time. When Kate accuses Leonard of failing to read far enough to identify her narrator, he snaps, “Don’t defend yourself. If you’re defending yourself, you’re not listening. I do know who your narrator is. She’s an overeducated, completely inexperienced, sexually inadequate girl who has rich parents who give her everything and who has nothing to say, so she sits around and thinks about Jane Austen all the time. I don’t give a shit about that person.” The other students leap to Kate’s defense, but Leonard’s got their number: “You’re all going to be nice to her now because her story tanked. But you’re not in this together. And trust me, you wouldn’t think the story was so great if it really were any good. If it were really good? You’d fucking hate it. Writers in their natural state are about as civilized as feral cats.”

If only! We’re here to watch these people fight and fuck, right? Yet Rebeck insists on analyzing and, too often, redeeming, their actual writing. We’re treated to long, drippy moments of false suspense, where actors stare furiously at pieces of paper, take in tense sucks of breath, and then pronounce the work incompetent or ingenious. More of the latter than the former, unfortunately. Blood! We want blood! Alan Rickman’s on the marquee, for Sade’s sake. Let him put the hurt on!

And he does, for a good while, even though most of his punches are telegraphed. Leonard leaves some big, purple bruises, too, which, showy as they are, comprise the best moments of Seminar. Director Sam Gold (the master sculptor of social awkwardness behind Circle Mirror Transformation) ensures that the haymakers land with satisfactory smacks and has assembled an astonishingly talented cast who give as good as they get. O’Connell, a screen star who’s new to the stage, pulls down broad laughs as Douglas, a very specific genus of cocktail-party opportunist who’s kept just this side of caricature. Park has fearless fun with Izzy, a pretty thin part, and Rabe, as always, is brilliant: Whether we’re watching her eat herself alive under the withering criticism of Leonard or drown her sorrows in a bowl of cookie dough, she brings supreme sympathy and depth to a character who might well be worthy of neither. We assume, for a while, that this is her story, but it isn’t. It’s Martin’s. And this, I think, is a shame.

Expertly handled by Hamish Linklater but ultimately overtaken by the poverty of his character’s creative DNA — congenital errors in the inkwell — Martin is a kind of writer’s fantasy himself, a sort of X-chromosome equivalent of that most heinous male creation, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. There’s a pile of guilty nostalgia for the nineteenth-century novel in Seminar, and Martin sits atop it, on the Darcy-Heathcliff throne. He’s the prickly genius dream-dick with dammed up emotions, surprisingly tender naïveté beneath his external thorns, and (SPOILER ALERT) enormous repositories of secret talent. Yes! There are whole Finding Forresters of petrified potential just waiting to be hydrofracked out of Martin by the right gal, the right mentor, the right whatever. He lacks only that catalyzing elixir we’ve collectively decided all men under 40 lack, Gumption. Undone by his own irony, cynicism, and fear, he awaits the great restoration of his confidence. For a while, we assume he’s simply the prize topiary in Kate’s Jane Austen fantasy garden and will find himself deconstructed along with the rest of it. Nope: He sticks around and jacks the whole play.

This is awfully sentimental stuff and utterly at odds with the poppin’ Hobbesian death match Rebeck promises at the play’s outset and sporadically delivers, with highly gratifying results. Alas, the playwright doesn’t seem particularly at home in a state of nature. For feral cats, these folks are fairly kittenish. Rebeck has taken a promisingly heartless situation and crowded it with heart and hurt and strange, unbidden consoling that ultimately verges on self-help. She’s far too gentle with these people. Who, by the way, aren’t. As Kate exclaims in a key moment of betrayal: “Writers are not people.” Seminar seems to be debating this point seriously. It should’ve just embraced it and let the fur fly.