By all rights, Joe Berlinger and Bruce SinofskyÔÇÖs Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory (HBO, 9 p.m. Eastern) should feel more triumphant than it does. It is, after all, about the release of the West Memphis Three, men who were imprisoned┬áÔÇö wrongly, it now seems┬áÔÇö for murdering and mutilating three young boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, nearly two decades ago. When convicted killers Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley Jr. were sentenced back in 1993, they were mere boys themselves, high school kids with pimply skin and uncertain voices.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Free the West Memphis Three, a legal defense fund, the once seemingly impregnable case against them fell apart, exposed as circumstantial and shoddy and tainted by ineptitude and bureaucratic self-protection. When Berlinger and Sinofsky visited West Memphis in 1996ÔÇÖs Paradise Lost, it was the story of a court case, pure and simple, and the filmmakers viewed it with an ominous and slightly clinical detachment. By the time they made their follow-up, 2000ÔÇÖs Paradise Lost 2: Revelations, the trio were already starting to seem like victims of a witch hunt. When theyÔÇÖre finally let go at the end of Paradise Lost 3┬áÔÇö the result of a bizarre plea-bargain arrangement that IÔÇÖll get into shortly┬áÔÇö there is a sense of relief and a surge of sentiment, but itÔÇÖs fleeting, and in the end itÔÇÖs eclipsed by a sense of emotional, physical, and spiritual exhaustion. Berlinger and Sinofsky titled this movie before the trio found out they were finally going free, but the word ÔÇ£PurgatoryÔÇØ still fits, because it encapsulates their predicament over the last eighteen years. The trio was condemned not just to rot in prison, but to wait for a resolution, an exoneration, that most people figured would never come.

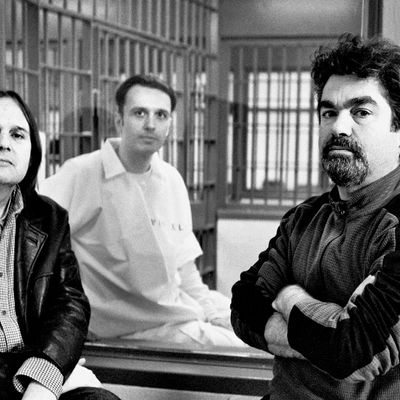

Like a lot of people, IÔÇÖve been following this series, and this case, for nearly twenty years, watching life unfold around me in all its splendor, terror, and tedium, seeing the seasons change, watching my kids grow up. Echols, Misskelley, and Baldwin were denied all of that except for the aging. When they got out of prison last fall, they had to teach themselves how to eat with utensils again. Time is as much the subject of this documentary as legal machinations. Part of what makes it so haunting is the spectacle of changing faces and bodies┬áÔÇö and a changing medium, represented by battered and scratchy early film footage gradually giving way to videotape, then digital video. The judges, lawyers, and activists age onscreen along with the West Memphis Three, thickening and going grey, but weÔÇÖre constantly aware that whatever other indignities they suffered, at least they were allowed privileges denied to these imprisoned ÔǪ oops, I almost typed ÔÇ£boysÔÇØ because I was looking at a black-and-white photo of Echols with his long, stringy, nineties goth-teen hair and his baby face; men, I meant to say.┬á

When I first saw Paradise Lost 3 at an HBO screening last fall┬áÔÇö with the trio in attendance┬áÔÇö the news of their release was so fresh that the filmmakers had to rush to affix a coda to a movie that had been made with the presumption that theyÔÇÖd be stuck in prison forever, that nothing was ever going to change. Yet the filmÔÇÖs overall effect was still infuriating, because it showed three men being scapegoated and imprisoned by a corrupt criminal justice system, one that was, and remains, less interested in determining guilt or innocence than in constructing the illusion of justice, and with protecting lawyers, judges, and politicians against taking responsibility for their actions. You canÔÇÖt really cheer anybody in circumstances like these. You can only marvel at the extent of human duplicity and self-interest.

You neednÔÇÖt have seen Paradise Lost parts one and two to be able to appreciate this documentary. Berlinger and Sinofsky have woven so much backstory into their narrative here that the third film suffices as a distilled summary of the whole weird, sad saga. You hear about how Christopher Byers, Michael Moore, and Stevie BranchÔÇÖs bodies were found hacked up in a ditch in West Memphis, and how Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley were deemed likely suspects at least in part because Echols, the leader of the group, was a black-clad and emotionally disturbed metal-head weirdo, and how the entire state seemed to succumb to hysteria over Satanism during the run-up to the first trial, and how the burgeoning movement to free the West Memphis Three was dampened by the justice systemÔÇÖs built-in self-protective mechanism, which seems built around maintaining the fiction that the state can never be wrong.┬á ItÔÇÖs all still sickeningly Kafkaesque. Berlinger and Sinofsky make a running (very dark) joke out of a narrative refrain: Over the decades, motions to review old evidence, introduce new evidence, or otherwise challenge the stateÔÇÖs case were repeatedly denied and overruled by the very judge who sent the trio to the slammer in the first place.┬á Richard Nixon had less ability to cover his own ass.

It was only after a team of experts hired by Free the West Memphis Three demolished the case against the trio that the state got nervous and allowed them to enter whatÔÇÖs known as an Alford Plea, which allows convicts to go free while proclaiming their innocence, while also admitting that sufficient evidence exists for the state to prove their guilt; in essence, it allows the state to continue to insist that they didnÔÇÖt make any mistakes, that they got the right guys. (The trio was sentenced to time served and is theoretically still guilty.)┬áParadise Lost 3 never loses sight of the sickening black humor of it all┬áÔÇö how Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley became, in effect, mere extras in a shadowplay about the omnipotence of the state. In the shadow of such sickness, all the personal dramas canÔÇÖt help but pale, but there are still surprising and powerful moments, not the least of which is the scene in which John Mark Byers, the murdered Chris ByersÔÇÖ adoptive father and a suspect himself, reads a letter from Echols forgiving him for his public statements proclaiming the trioÔÇÖs guilt and wishing for their deaths.

ThereÔÇÖs a secondary narrative in this trilogy, one that will admittedly be of interest mainly to journalists, historians, and film students: Berlinger and SinofskyÔÇÖs gradual evolution from ÔÇ£objectiveÔÇØor at least detached observers to doubting and trouble-making skeptics to openly partisan activists┬á advancing a particular interpretation of events. If you watch the three movies in a row you can see it happening onscreen, this shift.┬á The first movie, like the duoÔÇÖs debut┬áBrotherÔÇÖs Keeper, is a work in the Maysles Brothers/D.A. Pennebaker school, a fly-on-the-wall movie; its only auteur flourishes are the Metallica score and the swooping helicopter shots that suggest the point-of-view of winged demons swooping low in search of fresh souls to steal. The second film is the least perfect, most wrenching, and in some ways the most fascinating entry in the trilogy, because it shows the West Memphis Three, the murder victimsÔÇÖ families, the state, and the filmmakers all buckling beneath the weight of crippling doubt and anger that they canÔÇÖt really direct anywhere. The second movie is about that mix of paralysis and rage that afflicts people who arenÔÇÖt satisfied with the outcome of a story; itÔÇÖs about feeling in your gut that things arenÔÇÖt right but lacking the tools or the power to alter the narrative, and the agony that comes with realizing your own powerlessness.┬á The third movie was made by directors who had cast off received wisdom about what proper documentary filmmaking is supposed to be. TheyÔÇÖve probably wrestled with doubt over this since 1993, and maybe they still do, but I suspect those feelings subside when they watch Damien Echols eating pie with a fork for the first time in eighteen years.