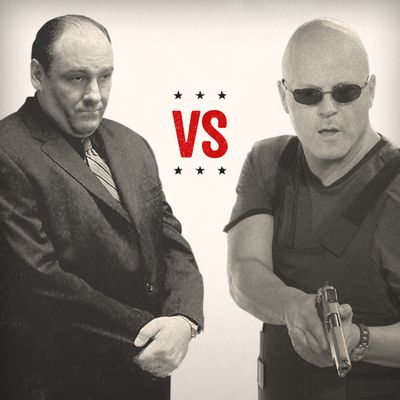

Welcome to the second round of Vulture’s ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. Today’s battle: Writer Heather Havrilesky judges The Sopranos versus The Shield. Make sure to head over to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, where Vulture fans’ votes have already diverged from our judges’. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #dramaderby hashtag.

Michael Chiklis is American cheese to James Gandolfini’s aged Parmigiano, lunchmeat to Gandolfini’s veal cutlet, malt liquor to Gandolfini’s Glenlivet 12. That’s what plenty of viewers were thinking when Chiklis won the Emmy for Best Actor in a Drama Series in 2002. Most of us hadn’t even seen The Shield at that point, and had barely heard of FX, the upstart, non-premium cable channel it rode in on. To add insult to injury, Chiklis didn’t mention his character Vic Mackey’s obvious debt to Tony Soprano in his acceptance speech. Since 1999, when The Sopranos premiered on HBO, the drama had single-handedly made the small screen safe for well-intentioned thugs like Vic. Thanks to Gandolfini (and David Chase, of course), Tony Soprano quickly became the gold standard for the conflicted man-child, the haunted ogre, the vulnerable but punishing patriarch. Gandolfini was rewarded for his efforts by winning the Emmy in 2000 and 2001, and again in 2003, the year after Chiklis did, in true Tony Soprano grind-your-face-into-the-pavement style. So in 2002, as Chiklis got choked up and sang the praises of “his cast,” many of us wondered how this strange little bald man could’ve snagged a golden statuette just by serving up his sweaty, conflicted, corrupt-cop copycat sauce.

Then we caught up. Or rather, we were tossed into the churning sea of suspense and awkward camaraderie and uncertainty and temptation and guilt that is The Shield. The notion that Vic Mackey was a cheap imitation of Tony Soprano soon felt as quaint as the décor in Artie Bucco’s restaurant. In fact, Vic represented a completely different sort of beast from Tony. Instead of blithely bashing in kneecaps with a baseball bat in order to keep the McMansion humming and the Scotch flowing, Vic was a working-class guy with serious marital and money problems, not to mention a kid with autism. And Vic initially strayed from protocol to sidestep the pointless bureaucracy of the police department, thereby sending as many “bad guys” to jail as possible.

Yes, much like your average 6-year-old, Vic Mackey loved calling criminals “bad guys.” There was something almost intoxicating about that: The cop who veers off the book over and over, but does so for the sake of “sending bad guys to jail.” This was how Vic saw it, anyway, conveniently overlooking the part where he skimmed from the bad guys’ stash to line his own pockets. In fact, Vic’s absurd knack for casting himself as one of the good guys became part of the spectacle. It was transfixing to watch a cop taking bribes, seizing cash and drug evidence, roughing up gang members on the sly, turning off surveillance cameras, kicking in doors without a warrant, all the while clinging to this very crude notion of the world as split neatly into two sides, the good and the bad, and somehow still casting himself as a hero. As he slipped farther down this ethically questionable path, Mackey reminded his boys (with indoctrination techniques that would’ve made Jim Jones blush), “Hey, we’re the good guys, here” and “We’re just doing this for our families.” Every time they wanted out, he pulled them back in. Vic, their mean daddy, the Great Santini of all dirty cops, was the kind of guy who could plant evidence, blackmail a city official, and beat someone with a tire iron, and consider it all an honest day’s work.

One of the great pleasures of The Shield, of course, was watching Vic Mackey realize (in slow motion, as the world around him spun faster and faster), that he wasn’t one of the good guys, not even remotely. He might’ve recognized this long ago, having shot and killed a fellow cop who was snitching on the strike team in the show’s pilot episode. Instead, after being stalked by the vicious head of the Armenian mob and having his strike team disbanded, Vic began to see that he’d moved so far past operating within ethical boundaries that he couldn’t quite wake up in the morning unless he first sliced off someone’s ear or stuck a loaded gun in someone’s mouth or hung someone up by a chain in the middle of an abandoned warehouse.

Sure, Mackey was hounded by guilt, and he was stumped, over and over again, by how to wriggle out of tight situations without mowing down everyone in sight with a semi-automatic. But there was something else in play: Mackey was unbelievably good at what he did for a living, particularly the dirty stuff. The joy of The Shield lies not just in the show’s breakneck pace, not just in the naturalistic, stuttery chatter between real good cops (who were never rewarded for it) Claudette and Dutch, not just in the unforgettable performances by CCH Pounder and Glenn Close and Forest Whitaker, not just in that catchy, super-aggro theme song (Dat-datta-datta-daaah!) that could keep you up all night, watching one episode after another. The real joy of The Shield lies in the fact that Vic Mackey loved his job.

While Tony Soprano sulked and second-guessed himself, Vic Mackey was all squinty focus, running through his flanking maneuvers, anticipating various twists and turns in the battle, soothing this guy while making that guy disappear, collecting aces in the hole, studying his enemies’ weaknesses. Vic Mackey was a strategic mastermind who was always in the zone. Watching The Shield, with its smart plotting and quick pace and surprise twists, was at once addictive and satisfying. Although, at first glance, Vic could look like a simpler, less complicated bad guy, over the course of seven seasons he proved himself to be a twitchy, obsessive-compulsive, savior-complex narcissist with a hell of a work ethic.

In other words, he was just like you and me.

You watch The Shield not to savor creator Shawn Ryan’s use of music or parallel imagery or masterful dialogue, then. You watch it because you can’t stop watching it. And you can’t stop watching it because you want to see Vic Mackey land on his feet, one more time. You hate the guy. You really do. But you love him, too, and you want him to win. You want that creepy, controlling, murderous, sexist bald man to win, win, win, and win again, God help you. And he does win again and again.

Until the series finale, when Vic finally loses. (For the uninitiated, spoilers follow.) Sure, he lands on his feet again, but only by selling everyone he cares about up the river in the process. Vic secures an immunity deal for himself by implicating his only remaining friend (and partner) Ronnie, and by confessing every last one of his countless sins over the years, as his colleagues look on, slack-jawed in disbelief. Meanwhile, Vic has driven his best friend Shane to kill his wife, his kid, and himself, and Vic’s ex-wife and kids have joined witness protection, ensuring that Vic will never see them again. In the final scene of the show, we find Vic stuck behind a desk in a gray cubicle where he’ll spend the rest of his career. Vic does pull a gun out of his desk, demonstrating that he’s not going to take his fate lying down. But it’s clear that his days of gaming the system are over.

We witness the end to Vic Mackey’s story, in other words. And there’s a moral there: Bad guys eventually pay the price for their misdeeds.

The same cannot be said for Tony Soprano’s story. But then, the feeling you get from watching The Shield is very different than the one you get from watching The Sopranos. Unlike the satisfaction and fist-pumping high that accompanies Vic Mackey in all of his inglorious glory, a great episode of The Sopranos leaves you feeling stunned, like you’ve just witnessed something precious and fleeting, a true work of art. To merely consider Tony Soprano, sitting by his pool, waiting for the ducks to come home, is to be sent into a state of moody contemplation. To recall the ugliness and loneliness of Tony’s divorce from Carmela, the way he loomed around his old house like a clumsy stranger, the way he struggled to connect with his alienated kids, is to be sent into paroxysms of fear over the uncertainty of marriage and family, those two pillars of American life.

But so many scenes from The Sopranos packed an enormous emotional punch: Tony mooning over his racehorse, Pie-O-My; Tony dreaming of former buddy Big Pussy as a talking fish on ice; Tony spotting the child’s seat in the back of Michael’s totaled SUV and realizing that the world would be better off without his screwed-up nephew in it.

Even the sight of Tony disaffectedly tossing back drinks while naked girls half-heartedly twirl in the background, the way he did in so many episodes, ushers up mixed feelings about the lonely nature of success. David Chase treated us to scenes that were so thoughtfully crafted and beautifully enacted, so rich with melancholy and depravity that they had the power to stir up the deepest wells of longing and regret. If Vic Mackey was the very satisfying anti-hero of a genre page-turner, then Tony Soprano was more like the complex protagonist of a literary classic.

Tony’s fragility, his brooding, his nostalgic fixation on childhood loomed in every scene. He was a character who wriggled free every time you tried to pin him down, who created more messes than he cleaned up, and who left us with more questions than answers. Even though he might casually kill someone and go grab lunch afterwards, the base level of denial he had to maintain took a grueling psychic toll on him that could only be temporarily numbed by women and alcohol. In Tony, we confronted the naïve hopes of a boy, butting up against the crushing weight of adult responsibility and the dizzying temptations of escapism. Chase may have sought, more than anything else, to unearth the blindly ignorant violence of these men, their sickness and selfishness reflected in the thoughtless nature of their crimes. But Tony was the one character who recognized the darkness and cruelty of his world. He bore the weight of that recognition, and it showed in his heavy stride, his clumsy hands, his defeated face.

Ultimately — in so very American a fashion — Tony held off the darkness for one more day with … onion rings and Journey. That was Chase’s not-very-ambiguous-after-all ending: Tony Soprano wasn’t treated to sweet rest, courtesy of a shotgun to the back of the head. No. Instead, he was damned for all time, damned to shove fried stuff in his face while trading pointless small talk, haunted by a song from his glory days.

Plenty criticized Chase for the way he chose to end The Sopranos — not by offing Tony or sending him to jail or wrapping up what some saw as unfinished threads of that saga, but by keeping Tony suspended in sap forever. But Chase’s choice wasn’t a cynical one. It was an artist’s choice (more specifically, the kind of choice an artist makes when he’s not self-consciously wondering what an artist would choose). Chase treated us to a character who embodied so many American weaknesses: Pure selfishness rationalized through misguided notions about “family,” brute force rationalized by illusions about “loyalty,” macho superiority and sexism rationalized by romantic notions about patriarchal birthright, guilt and self-hatred numbed through alcohol, music, drugs, junk food, and sports trivia. And after shoving this lovable, sick, childlike, horrifying mirror in our faces week after week, he refused to kill Tony or even seal his fate, to let us put it all behind us and move on. Like the very best scenes from The Sopranos, which were so full of sadness and humor and beauty that they’re impossible to forget, that last image of Tony’s face, frozen in time forever, made it impossible to forget Tony and what he did to our view of ourselves as Americans, at the end of our glory days.

Although he presented his own twisted mirror on the American dream, embodying the paternalistic arrogance that good intentions always justify dirty deeds, Vic Mackey never quite achieved the same resonance that Tony Soprano did. Even though Vic was just as memorable as Tony, from his dodgy compulsion to hedge rather than come clean to his peculiar mix of self-delusion and grandiosity, we can close the book on Vic Mackey the way we fall out of touch with an old friend from high school. We can’t forget the thrills and suspense of The Shield’s reckless joy ride, but we can move on. Vic was a blast, but those days are gone now.

Tony, though, still loiters in our psyches. Like a dead father or brother, like a lost love, like the better or worse version of ourselves that stood in for us once upon a time, Tony is still in that goddamn diner, shoving onion rings in his mouth. Even at its most surreal or perverse, the mournful palate of The Sopranos always felt dangerously personal. The Shield may be the most dynamic cop drama in TV history, but The Sopranos bestrides the narrow world of cop dramas like a colossus. We’ll take Tony Soprano to the grave with us. Damn you, David Chase!

Winner: The Sopranos

Heather Havrilesky (@hhavrilesky) is a regular contributor to the New York Times Magazine and the author of the memoir Disaster Preparedness.