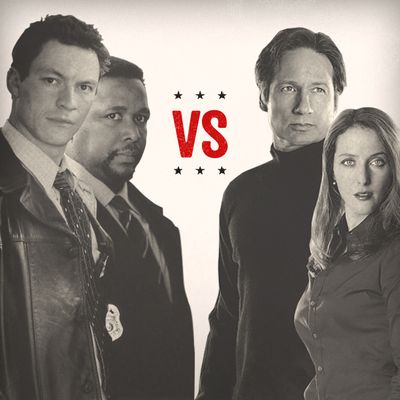

Welcome to the second round of VultureÔÇÖs┬áultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until┬áNew York┬áMagazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. TodayÔÇÖs battle: TV and comic book writer Marc Bernardin judges┬áThe X-Files┬áversus┬áThe Wire.┬áMake sure to head┬áover to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, where Vulture fansÔÇÖ votes have already diverged from our judgesÔÇÖ. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #dramaderby hashtag.

Chris CarterÔÇÖs The X-Files was the show we didnÔÇÖt know we wanted. When it debuted in 1993, science fiction wasnÔÇÖt completely alien to TV: Star Trek: The Next Generation was in its fourth season, and its spinoff, Deep Space Nine, would premiere the same year. But, for the most part, televised sci-fi had been tucked away in the geek fiefdom, and it would be years before being a geek was cool. With The X- Files, Carter brought science fiction out of the basement, and into the light.

The brilliance of The X-FilesÔÇÖ conceit wasnÔÇÖt apparent at first. Sure, it was always a show about two FBI agents who investigated cases that defied conventional explanation. One of them was Fox Mulder, the Believer, who wanted ÔÇö no, needed ÔÇöto know that the truth really was out there. The other was Dana Scully, the Skeptic, for whom the rule of science was the rule of law. And so they fought, in ever-so-hushed tones:

ÔÇ£Mulder, can you really believe that man is a telekinetic?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Scully, give me another explanation and IÔÇÖll take it.ÔÇØ

And so it went. But a mass audience that didnÔÇÖt want to go to outer space for their entertainment found a show they could recognize: It was a detective show, starring people who pointed their guns at things.

It helped having stars so damned pretty. Not 90210 pretty, but the kind of pretty you saw staring back at you over the office copier. The kind of pretty that was cloaked in boxy suits and painfully bobbed hair. You always knew that David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson had something else going on under the hood and you hoped that, maybe, weÔÇÖd eventually get to see what.

It took a while, though. The first season was rather hit or miss: For every episode that introduced a memorable character like The Smoking Man or Tooms, there were hours that just steadfastly refused to engage the audience. Not only did it take a while for Carter and his writing staff to find their groove ÔÇö that seductive mix between monster-of-the-week and alien-conspiracy mythology ÔÇö it took both Duchovny and Anderson some time to find the nuances within their characters, the dogged yearning of Fox Mulder and the spurned child buried inside Dana Scully. But that mythology was in place by the second season and by the third, Carter was able to take chances, to push the boundaries of the format that he himself put in place. As a result, seasons three through six of The X-Files are as strong a stretch of genre TV as weÔÇÖre ever likely to see, with harrowing stand-alone episodes that merrily messed with what we thought the show should be (like ÔÇ£Pusher,ÔÇØ which showed the crippling downside of getting everything you want) and wild explorations of that dense mythology (as in ÔÇ£Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man,ÔÇØ which laid bare The X- FilesÔÇÖ most consistently mysterious character) that raised the bar of what the show could be.

And then the wheels came off a bit. Duchovny would eventually leave the show and without him ÔÇö and his seemingly never-ending quest to find his abducted sister ÔÇö The X-Files lost some steam. (As fine an actor as Robert Patrick may be, he wasnÔÇÖt enough to hold the center.)

But when it was good ÔÇö no, when it was great ÔÇö The X-Files took the best of shows that came before it, like The Twilight Zone and Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and synthesized something thoroughly modern. It was the first of a new breed of television show that would allow a mass audience to feel what it was like to be a geek. To faithfully set their VCRs (remember those?) to ensure they didnÔÇÖt miss a single episode. To look for clues in each episodeÔÇÖs margins as if scouring the Dead Sea Scrolls. To download saucy desktop wallpapers of its ginger starlet. And it turns out, we loved being geeks.

Even though The Wire was borne from and took place in the crack-vial-studded underbelly of Baltimore, Maryland ÔÇö light years away from the FBI Headquarters in Langley, Virginia, despite them being less than a tank of gas from each other ÔÇö The Wire was equally geeky, in its own darkly humorous way. Like The X-Files, it was stocked with minor characters beloved by ardent fans; it told long, reaching story lines that occasionally ÔÇö aw, hell, always ÔÇöwrapped up without the convenience of closure; it had a skeptical view of the government, which protected its own interests above all else; and there were bonds between characters, both platonic and romantic, that made the dreams of ÔÇÿshippers come true.

But if The X-Files is like a great album, filled with killer singles and excellent deep cuts, then The Wire is a phenomenal novel, with a sprawling cast, swirling themes, and tragedy up the yin-yang. Created by former beat reporter David Simon, The Wire answered a simple question in, perhaps, the most complex manner possible: What effect does the drug trade have on inner-city Baltimore? And, like Carter did before him, Simon took the cop show, a framework that viewers could understand, and used it to tell his epic tragedy, to take his audience from the street corners, where the rock meets the road, through the schools and the docks, inside a mayoral campaign, and finally to the media tasked with trying to cover all of it.

The Wire was so different, so ambitious, so new, that it all but taught you how to watch it as you were watching it. No show before it moved with such a deliberate pace ÔÇö you could watch the first few episodes and not know, precisely, where it was all heading. You knew that life on the corner was no joke. You could sense that cops like Detective Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West), Lieutenant Cedric Daniels (Lance Reddick), and Detective Kima Greggs (Sonja Sohn) were a bit out of their depths dealing with criminals like Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris), Stringer Bell (Idris Elba), and Marlo Stansfield (Jamie Hector) ÔÇö much like Scully and Mulder were consistently rocked back on their heels by shape-shifters, backwoods cannibals, and weird-ass pseudo vampires. And you didnÔÇÖt know what the hell to make of the mesmerizing Omar Little (Michael K. Williams), the unflappable stick-up man who loved boys almost as much as he loved money. (William B. DavisÔÇÖs Smoking Man filled that same mercurial role on The X-Files, but with a bit less swagger.)

The story threw people and places and crimes at you, not giving a damn if you were on the same page, or if you were keeping up. Morality was as elusive as quicksilver, constantly shifting on a playing field that refused to remain level, and justice wasnÔÇÖt delivered in a courtroom nearly as often as it was dispensed on the streets. Then, around four episodes in, The Wire just clicked, the same way Shakespeare starts to make sense about twenty minutes in. What felt like disparate story threads began to weave into a tapestry of despair. And by the end of that first season, The Wire emerged as a singular achievement in television; a testament to truth that only fiction could deliver.

And then, Simon and Co. did it again. And did it better. And better. And better.

Where The X-Files had a pair of characters that started as ciphers, only to gain depth and texture as time passed, The Wire had a gallery of rogues on both sides of the law that were fully realized out of the gate and only got more complex as the show went on. Where The X-Files sucked viewers in with horrific monster-of-the-week stories and hooked ÔÇÿem with dense alien conspiracies, The Wire unspooled its tale of the tarnished American Dream with measured patience, tightening like an invisible vise until you couldnÔÇÖt breathe and werenÔÇÖt sure why. Where The X-Files had peaks of incandescence, surrounded by stretches of pendulous quality, The Wire was a sustained siege of brilliance from soup to nuts.

Over five seasons, The Wire made its case as the most rewarding drama on TV. It wasnÔÇÖt an easy show to watch. It required work and fidelity. It demanded that you keep a running tally of crooks and cops, politicians and players, and assorted secrets, lies, and whispers so that when they all got pulled out of the continuity toy box ÔÇö as they all inevitably would be ÔÇö you knew who was who and why they mattered. And if you put in the time, The Wire would deliver unto to you what I consider the best show in the history of television. Period.

Winner: The Wire

Marc Bernardin (@marcbernardin) writes for TV (most recently for SyfyÔÇÖs Alphas) and comic books (DCÔÇÖs Static Shock).