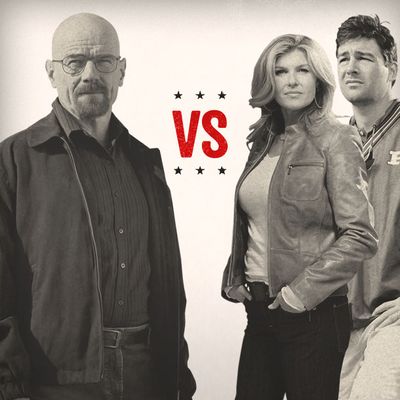

┬áFor the next three weeks, Vulture is holding the ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. TodayÔÇÖs battle: Author Steve Almond judges Breaking Bad vs. Friday Night Lights. You can place your own vote on Facebook or tweet your opinion with the #dramaderby hashtag.

If you want to know why people get so evangelical about Friday Night Lights, consider for a moment the strange case of Tyra Collette (Adrianne Palicki). SheÔÇÖs tall and blond and beautiful. Her role, in the world of your standard high school football drama, should be simple. SheÔÇÖs there to serve as a designated groping dummy for the first team.

The problem is Tyra refuses to play to type. We know this because we see her at her job as a waitress. ItÔÇÖs the eve of yet another big game for the Dillon High Panthers, and a car full of hooting players drives by. Her customer, a handsome young executive from Los Angeles, asks what the hubbub is all about. ÔÇ£Just a bunch of overheated jocks too dumb to know they have no future, fighting over a game that has no meaning, in a town from which there is no escape,ÔÇØ Tyra mutters.

A bit later, Tyra, making her play for the exec, brings him dinner out at an oil well hes surveying. You know what else I hate, she tells him. Oil. I hate what it did to my father, this whole town really  I mean, its worse than crack. These dealers come in promising good times that last forever, and just as fast, its gone. And all the moneys gone with it.

ItÔÇÖs moments like this that make FNL such a subversively brilliant show. ItÔÇÖs not just that Tara is exploding our various small-town pieties, or exposing the human cost of our crude addiction. ItÔÇÖs that Tyra herself sees things that leggy young thangs on network television arenÔÇÖt supposed to see. SheÔÇÖs too smart for her circumstances, and desperate to find a larger fate.

Which is true of FNL itself. The show refuses to live within its given parameters, as a post-pubescent Peyton Place in shoulder pads. Instead, it stubbornly exposes the underside of our national obsession with winning. What does it mean that an entire community comes to depend on the athletic combat of its young men for validation?

This question haunted the show from the start. Which is why the pilot introduced not just the players, but the coterie of adults whose interests in them is both tender and pathological. We see unctuous boosters verbally molesting head coach Eric Taylor (Kyle Chandler) and shifty recruiters working over parents during a practice. The show makes no bones about the ways in which high school football has become a de facto plantation for fresh talent. It hardly comes as a surprise when, early in the first season, DillonÔÇÖs star running back, Smash Williams, injects himself with steroids.

The dark truth of FNL is that itÔÇÖs tragedy posing as melodrama. The cinematography presents Dillon as a hard-bitten town of mostly exhausted hopes. We see an empty main drag on game night, the wide Texas dusk falling behind a bank of sodium lights ÔÇö images that have about them a sorrowful majesty.

In fact, itÔÇÖs this persistent sense of Dillon as an underdog that makes its inhabitantsÔÇÖ hard-won victories feel momentous: coach TaylorÔÇÖs ability to lead his players to unlikely championships; Smash finally making it to college; Tyra finally finding her larger destiny. Nothing comes easy.

I can still remember watching the pilot, six years ago, which culminates with the PanthersÔÇÖ season opener. By all rights, DillonÔÇÖs all-state quarterback Jason Street (Scott Porter) should lead his teammates to a thrilling comeback win. Instead, toward the end of the game, he throws an interception and is paralyzed trying to make a tackle. The sequence immediately made me think of James WrightÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio,ÔÇØ a poem about young men who grow suicidally beautiful/At the beginning of October/And gallop terribly against each otherÔÇÖs bodies. (Ask yourself this: whenÔÇÖs the last time a television show made you think about a poem?)

In a nation blithely obsessed with sports, Friday Night Lights represents an unprecedented achievement: a fearless investigation of our fandom, and the prices paid when we turn a childrenÔÇÖs game into a form of hero worship.

There are no heroes, as such, in Breaking Bad. The show is about a mild-mannered high school science teacher named Walter White (Bryan Cranston) who is diagnosed with cancer and turns to cooking meth to pay his astronomical medical bills, and to provide an inheritance for his family.

Breaking Bad is about a lot of things: illness, mortality, family loyalty, the economic anxieties of the post-Bush hangover, AmericaÔÇÖs perverse drug policy, the tolls of greed. Mostly, though, itÔÇÖs a show about the narcotic effects of pure fucking evil.

And when I say evil, IÔÇÖm not talking about the suave violence plied by cableÔÇÖs slick sociopaths, your Tony Sopranos and Dexters and Marlos and Al Swearengens. Those guys are categorically evil. TheyÔÇÖre fascinating to watch because they enact our fantasies of power and violent release. What makes Breaking Bad revolutionary is that Walter White is one of us ÔÇö a civilian, a model citizen, a patsy.

And what has all this servility gotten him? As the series opens, we find Walt working at a car wash to supplement his teaching income. HeÔÇÖs got a pregnant wife and a teenage son with cerebral palsy to support. Then he gets handed what amounts to a death sentence, a diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer. In short, heÔÇÖs been shit upon by fate.

By the end of the first episode, heÔÇÖs teamed up with a burnout former student named Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul), constructed a mobile meth lab, been kidnapped by two murderous dealers, and poisoned them. It looks far-fetched on paper. But the miracle of Breaking Bad is that every plot twist feels not just astonishing, but inevitable.

Season Four, for instance, opens with Walt and Jesse being held hostage for having murdered a co-worker from the high-tech lab of drug lord Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito). When Gus arrives, he calmly slits the throat of his most loyal lieutenant, rather than Walt or Jesse. The execution is essentially a warning, one that guarantees Walt and Jesse will continue to cook for Gus.

ThereÔÇÖs a lot of mayhem in Breaking Bad. But it isnÔÇÖt the airbrushed variety served up elsewhere. The violence feels real: itÔÇÖs abrupt and chaotic and often senseless. When Jesse suffers a beating, the bruises last for weeks.

And the physical violence isnÔÇÖt even the scariest thing on display. ItÔÇÖs the emotional violence that Walt does to himself and to his family that proves most wrenching. What weÔÇÖre watching in Breaking Bad is a man driven to crime not just by misfortune, but his own suppressed rage. Walter White isnÔÇÖt a natural born killer. He evolves into one before our eyes.

Consider the showÔÇÖs best episode, ÔÇ£4 Days Out,ÔÇØ which comes toward the end of season two. As it opens, WaltÔÇÖs first round of treatment has ended. HeÔÇÖs now spitting up blood and convinced he will die in a matter of weeks, so he and Jesse head out to the desert to cook up one last epic batch of meth, nearly starving to death in the process due to the usual Jesse carelessness. WaltÔÇÖs genius as a chemist eventually winds up rescuing them, and at the end of the episode, back in civilization, WaltÔÇÖs doctor reveals that heÔÇÖs in remission. The rest of his family is overcome with gratitude and relief. Walt himself heads to the bathroom in a state of shock. He should be ecstatic. But the ugly truth that WaltÔÇÖs been hiding from himself is that he doesnÔÇÖt want to be cured, that the specter of death is whatÔÇÖs liberated him to act on his forbidden impulses ÔÇö and to feel truly alive. Without warning, he begins punching a metal paper towel dispenser with a viciousness that leaves his knuckles ribboned in blood. As a television viewer, I have never been as frightened, or enthralled.

As for the acting, itÔÇÖs basically invisible. Which is to say, the characters come off as more human ÔÇö more tortured and tender ÔÇö than most of the actual humans I know. The cinematography is breathtaking. Breaking Bad has a bona fide visual vocabulary, from the dreamy montages used to convey the liquid horrors of chemotherapy to the quick-cut sequences that capture the rush of meth use and criminal adrenalin. The show even manages to make a kind of grim poetry of WaltÔÇÖs hometown, Albuquerque, which we see as an island of artificial suburban order in an ocean of untamed desert.

It is, of course, ridiculously American to pit television shows against one another, as if they were politicians or beauty queens. But given that proviso, there are fundamental differences between FNL and Breaking Bad. The former is terrifically entertaining, and often moving. I enjoy watching it more than Breaking Bad. But this enjoyment arises, in some measure, from the fact that IÔÇÖm always aware the characters are going to be okay. In a deeper sense, IÔÇÖm always aware the characters are characters.

I never feel that way watching Breaking Bad. What I feel is a kind of simmering panic on behalf of its people, a feeling in my gut that IÔÇÖm somehow implicated by their sins. Which is what tips the scale in favor of Breaking Bad. ItÔÇÖs not just great television. ItÔÇÖs great art. The harrowing hook of the show is that we are all, in the private kingdom of our desires, Walter White: obedient creatures quietly, desperately, awaiting the chance to unchain our vicious animal selves.

Winner: Breaking Bad

Reader Winner as determined on VultureÔÇÖs Facebook page: Breaking Bad

Steve Almond is the author of seven books, most recently the story collection God Bless America.