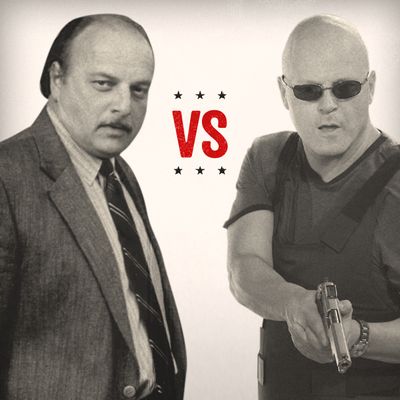

For the next three weeks, Vulture is holding the ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. Today’s battle: Vulture’s Editorial Director Josh Wolk judges The Shield vs. NYPD Blue. You can place your own vote on Facebookor tweet your opinion with the #dramaderby hashtag.

When The Shield first premiered in 2002 on FX — a network up until then known for reruns and NASCAR (and before that, a morning program co-hosted by a puppet) — the show seemed to be a crass attempt to Xerox HBO’s antihero model. Based on its logline, The Shield appeared to have just shifted The Sopranos to the other side of the law: Instead of focusing on a violent, amoral mob boss who proved disconcertingly likable because he loved his kids, the series centered around a violent, amoral cop who proved disconcertingly likable because he loved his kids. But The Shield’s pounding and perversely gripping pilot invited instant apologies by preemptive doubters: It revealed Vic Mackey to be a gleefully sociopathic and bullying Dirtier Harry, and his uniquely wicked charms demonstrated that creator Shawn Ryan could take two big-boy steps out from under David Chase’s shadow. Yet with all the focus on The Sopranos, few critics seemed to acknowledge that Mackey’s true debt was to another earlier TV character: NYPD Blue’s surly, misanthropic, and impulse-control-deficient Andy Sipowicz. Which makes deciding which one of their shows is superior a tricky balance: Does one go with the pioneer, or the one who built on his forefather’s groundbreaking work?

If someone were to draw a Darwinian sketch of the evolution of the antihero cop, Vic Mackey would be the next step forward out of the water. The less evolved Sipowicz (Dennisum Franzlicicus) is hunched with a slightly Neanderthal brow, under which his eyes constantly and nervously shift, and he responds animalistically to danger or distrust. The Mackey (Michlus Chiklisunum) is bullet-headed, stands fully upright (and has lost all of his body hair), and though he is a violent creature, he has also mastered complicated psychological manipulation. Even the wardrobe has evolved: The Sipowicz wears unfashionable short-sleeved polyester dress shirts with ties that looked like they could be yanked off with one flick of a clip. The Mackey has learned vanity, strutting with tight T-shirts that show off his tanklike physique. (He resembles a buff, more nipply Baby Herman from Who Framed Roger Rabbit?)

However, both are, at heart, law enforcers whom a viewer should not in good conscience be rooting for. When NYPD Blue premiered in 1993, the reigning detectives on TV were the methodical, efficient Law & Order partners. While NYPD Blue co-creator Steven Bochco had previously debunked the idea of the flawless lawman in the eighties’ Hill Street Blues, most TV cops were historically brilliant and either quirky savants (Columbo) or slick renegades (Sonny Crockett). Even when the most unconventional small-screen cops played fast and loose with protocol (usually inspiring their long-suffering, by-the-book superiors to pound their desks and emptily threaten to take their badge), they were an inherently likable bunch, the kind that you would be happy to see show up at your door when you needed the law. But Sipowicz? Yikes. Cranky, racist, defensive, and perpetually aggrieved, he was a dark cloud in a ratty trench coat. He was angry when witnesses didn’t step forward, and when they did he was angry that they didn’t remember enough. Still, even as he threw recalcitrant suspect after suspect against the interrogation-room wall, slapped wife-beaters, and occasionally toyed with procedural niceties to make sure a case got closed, it was never in the pursuit of anything but putting a bad guy in jail. One look at his polyester wardrobe made it clear that this was not a man interested in using the law to profit himself. What would he spend it on: Glower lessons?

Mackey, on the other hand, was deft at nailing criminals, but always with an eye toward how a bust could be manipulated to profit him and his Strike Team (vulpine Shane; loyal but increasingly pained Lem; and — uh — mustached Ronnie). The vivid, cruel creation of Shawn Ryan (a veteran of Angel and Nash Bridges, two shows that didn’t hint at the writer’s massive, dark, and complex ambitions), Mackey loved the idea of family, but that was pliable. He doted on his three kids but cheated on his wife, who finally threw him out. Robbing drug dealers and the Armenian mob were ostensibly done to support his family, but unlike Breaking Bad’s Walter White, you never got the sense that that idea was ever anything more than a bumper sticker to Mackey. He wasn’t a complete sociopath: He was capable of empathy, showing stern concern for a prostitute informer and inquiring about her daughter, but was this his own paternal values, or the knowledge that he couldn’t afford to lose a good snitch? Both Sipowicz and Mackey were genius cops, but watching them it would never occur to you to want them assigned to your case: Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if your crime went unsolved after all.

So which flawed lawman had the better show? First, respects must be paid to the original squad. NYPD Blue was groundbreaking, challenging television: It instantly proved to be far more than the “adult language” and occasional flash of skin that sparked the apoplectic pre-premiere controversy but quickly became secondary. It introduced a language both verbal (skels, humps, “the boss is squeezing my shoes”) and visual (its skittery camera observed like a nervous witness), and deglamorized the cop show. Its dialogue, polished by Bochco’s partner, the profanity poet laureate David Milch (and inspired by adviser Bill Clark, a former NYPD detective), felt as authentic as the detectives’ cheap suits, with its grumbles, pain, and threats; the bursts of interrogation-room violence was electric.

Soapy story lines were interwoven around the cases, as with Jimmy Smits’s bumpy relationship with Kim Delaney’s alcoholic detective Diane Russell (though while Delaney was a great romantic foil, she was never quite believable as a cop), and stammering Medavoy’s improbable and yet charming flirtation with the bodacious receptionist Donna Abandando. As the years went on, the show fell into the trap of pairing off everyone in the 15th Squad (handing Russell off from Smits’s Bobby Simone to his replacement, Rick Schroder’s Danny Sorenson). And ultimately, these relationships were never as moving as the ones between Sipowicz and his partner of the moment. When Simone died, we felt more anguish for Andy than for widow Diane.

These extracurricular scenes followed the model of Hill Street, showing how bleak and violent day-to-day police work affects a person when he clocks out. And it often proved effective. No matter how absurd it might have seemed to have Sipowicz eventually marry A.D.A. Sylvia Costas (Sharon Lawrence), considering how his asshole bona fides were illustrated in the pilot by having him calling her a “pissy little bitch,” the writers deftly used their relationship to slowly humanize and educate Andy. In the standout season three episode, “The Blackboard Jungle,” Sipowicz faces off against the African-American Lieutenant Fancy after an arrested activist relays how Andy used the N-word. Sipowicz remains defiant until he returns home and recounts the trouble to pregnant Sylvia — and she sternly demands he never introduce racism to their child. The episode ends with his eyes uncomfortably shifting back and forth with a mix of stubbornness and guilt as he sits in their bedroom, visibly chastened. (The regularity with which Franz won his four Best Actor Emmys elicited grumbling of its predictability, but holy perp walk, he deserved them.)

The Shield also delved into its characters’ private lives. We saw Vic struggle with his kid’s autism, and his wife ignore all evidence of her husband’s corruption until finally kicking him out. The devoutly religious and rule-obsessed junior officer Julian wrestled to ignore his own homosexuality. Shane married Mara, who clawed the first cracks in Strike Team unity. The stupendously no-bullshit Claudette quietly struggled with health issues while her loyal partner Dutch struggled with what it’s like to be the smartest guy in the squad, but to be painfully unpopular because of his inability to stop reminding everyone of that fact. This was a deeper bench, and their off-duty lives were all the more potent because of the way they all informed the inexorable path to the series’ tragic, perfect finale.

Yes, that finale. Or as I call it here, “the ultimate decision-maker.” When we constructed this bracket, we decided that it was only fair to judge a show by its best years. So many dramas gradually lose the genius of their early seasons, and it’s all relative to their lifespan. Hell, Twin Peaks was legendary even as it was a bitter disappointment for a full half of its short life. And yet, bonus points must be awarded for a show that not only kept up its quality for its entire run, but which emerged an even better work of art at the close of its finale. That show is The Shield.

NYPD Blue stumbled in its old age. Milch famously began losing control of his work to his addictions, to the point that the cast was left waiting for him to spontaneously narrate their increasingly stylized language on set, a practice that finally broke Smits and motivated him to leave. Milch eventually left the show in 2000, and it became more conventional in its remaining years, as Andy became more cuddly. Yes, this was the logical endpoint to his trajectory, but there was still something painful about watching him setting up shop with his little boy and an even more nonsensical love interest, Charlotte Ross’s Detective Connie McDowell.

But how many dramas can sustain greatness for their entire life? Well, The Shield did. The pleasure and angst in watching this show in its early seasons was seeing Vic’s Strike Team take bigger risks and just barely avoid getting caught. And just as you started to think, How long can these “Wait, I’ve got a plan” escapes go on? it became clear that there was a grand and stunning endgame here. All of these big scams — Vic’s premeditated killing of a mole in the pilot, the robbing of the Armenian mob — didn’t exist as one-offs, they accrued to a giant unwieldy stockpile of secrets, lies and crimes that inevitably left the Strike Team paranoid and vulnerable. When Forest Whitaker’s indefatigable and increasingly imbalanced Lieutenant Cavanagh set about building a case against the Strike Team in season five, he picked apart any trust they had, even as Mackey evaded his traps and left Cavanagh one stick of gum short of a pack. The last two seasons of propulsively tragic episodes were all the more painful to watch because they were so inevitable: Of course this wasn’t going to lead to Butch and Sundance yee-hawing into the breach, partners forever. It led to paranoia and death and what I consider the greatest finale in television history. I’m loathe to spoil it, lest it deter any uninitiated viewers from watching, but suffice it to say it is nothing you’ve been trained to expect from TV, and everything TV should be. It is the rare finale that makes everything that led up to it seem even better, and the rare series that works as a single engrossing tale. Revisiting episodes of NYPD Blue made me want to watch a few more, but revisiting The Shield made me want to ignore my family, sequester myself, and rewatch all 88 episodes in a row. It’s true that without Sipowicz there would be no Mackey, and respect must be paid. But as much as I hate to squeeze Sipowicz’s shoes, The Shield is the better show.

Winner: The Shield

Reader Winner as determined on Vulture’s Facebook page: The Shield

Josh Wolk is the Editorial Director of Vulture.