In Brice MardenÔÇÖs two-gallery show at Matthew Marks, we see him reflecting, slowly circling back to the beginnings of his long career. HeÔÇÖs reconsidering ideas, techniques, materials, and surfaces, channeling his inner Mondrian, revisiting his neglected marble paintings of decades ago. HeÔÇÖs created grids and latticeworks of line interspersed with fields of pollenlike secondary colors that play off veins and blotches in the stone. The coolness of the marble surface crackles with the areas of fiery color. ItÔÇÖs great to see this artist who sometimes seems on automatic pilot experimenting, rethinking, taking chances, and flying by the seat of his painterly pants. I love that almost everything about these works is left unresolved. You could almost call the show ÔÇ£In Praise of Slowness.ÔÇØ

That wouldnÔÇÖt be a bad alternate title for its centerpiece, the ravishingly somnolent painting called Polke Letter. Although the great late German artist Sigmar Polke, alchemical lord of painterly phantasmagoria, has often given me the feeling I was visually licking a hallucinogenic toad, MardenÔÇÖs Letter exudes a kind of hypnotic retinal chloroform, making one hypersensitive to some slowed-down state of seeing and being.

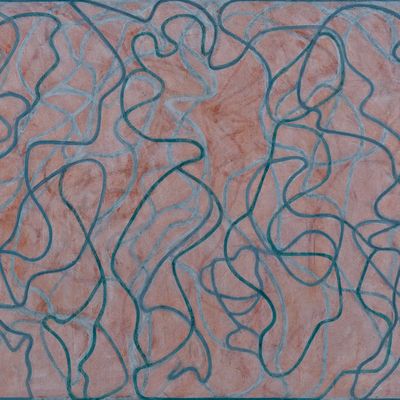

Looking at Polke Letter hanging alone in a small white room with a skylight is like visiting a Greek island. An abstracted stage-set with curtains open and blue pillars on either side, containing what look like snakes in a box, the painting gives off an aura of milky Mediterranean blue, a pale sapphire that mingles with hues of terra-cotta, matte ashy sienna, slip-colored gray, and something like soil. At points you can see all the way through to raw canvas. YouÔÇÖre pulled into and carried along an internal mesh of gliding lines shaped like runes and glyphs. These ribbon-things curve and arc in a faded field of reddish sedimentation. The formations echo late de Kooning, early Matisse, and Paleolithic wall painting. Snaking lines spiral gyroscopically inward, then navigate back to the borders, gracing or running along the top and bottom of the canvas like prehensile sightless organisms feeling their way to the borders of their worlds. Then they fall away, head elsewhere, and coil toward the left- and right-hand pillars of cerulean to do the same thing.

Marden has a thing about edges. HeÔÇÖs written that theyÔÇÖre ÔÇ£the infinitesimal hinge between.ÔÇØ Whatever they are, all this makes the painting an abstract aquarium, or a map of aromatic vapors. I see birds, bagpipes, convection currents, thermal forces, and dried-up riverbeds. I revel in the slow disorder of this new order.

MardenÔÇÖs show is slow in other ways. This work shows him inching forward, picking up from where we last saw him in 2010, in his series of similar paintings also called ÔÇ£Letters.ÔÇØ Here, however, he eliminates structured use of colors, no longer arranging them in the order of the spectrum. The space of Polke Letter is more atmospheric, unclear, less deft. (Real Marden-watchers will notice heÔÇÖs even let a couple of lines dangle in space ÔÇö a huge move for this ultra-circumspect artist, one that creates local concavities, triggering a sense that the whole surface is undulant.) All this adds life and spice to his work, making it more resilient, resistant, pleasurable.

At the end, we see him head all the way back. In a long, narrow nine-panel painting in which each canvas is one color, Marden, 73, retraces his way to the very beginning of his career and the monochromatic fields of encaustic paint that brought him to prominence. Here, however, instead of rendering the fleshy, full-bodied shapes of the past, Marden explores chalky boniness and skinlike thinness, patinas and tinctures of color that may have been evaporated or built up in stains or washes, caked with minerals, or otherwise burnished. These simple fields function as elemental forces like sea, sky, and earth. The row of canvases seems to form and reform in varying patterns, like stanzas of poetry. We see pairs and couplets become triplets that turn into irregular rhythms of celadon, azure aqua, robinÔÇÖs-egg blue. The paintingÔÇÖs title, Ru Ware Project, alludes to the last and smallest thing in the show, a shard of a Ruyao-glazed pottery bowl. Some will see the act of displaying this relic (and of Polke LetterÔÇÖs being hung alone) as precious and pretentious. Who cares? Remember that Matisse once saw a small piece of fabric in a shop window, bought it, and then turned its patterns into new visionary universes. Much of MardenÔÇÖs current work grows from this one tiny pottery chip, its otherworldly color, surface, sheen, textures, and presence. You come to see how artists ┬¡create whole worlds from tiny pieces.

Brice Marden. Matthew Marks Gallery,  502 and 526 W. 22nd St. Through June 23.