I hate art auctions. Not just because theyÔÇÖre freak-show legal casinos, spectacles where the ├£ber-ultrarich can act out as profligately in public as possible, trying to buy immortality, become a part of art history, make headlines, and create profit. I donÔÇÖt only hate them because they may be the whitest sector in the entire world. I hate them for what they do to art, for the bad magic of making mysterious powerful things turn into numbers.

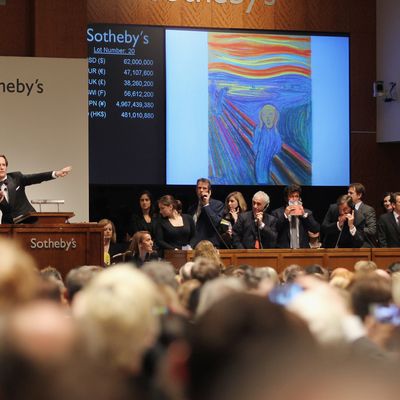

Last night, after being touted in the lamestream media as potentially the ÔÇ£most expensive painting ever,ÔÇØ Edward MunchÔÇÖs 1895 pastel The Scream came up on the auction block. The whole event amounted to about ten minutes of back-and-forth banter, during which the theatrical SothebyÔÇÖs auctioneer Tobias Meyer tempted the fates by cooing, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve got all the time in the world.ÔÇØ (I had such a vision of Wotan sweeping him up and whisking him off to the underworld right there!) With dapper white men and tall, thin white women making little finger signals while holding phones, speaking to strangers in Dubai or Russia or Beijing or Mitt RomneyÔÇÖs garage, the painting was sold ÔÇ£to an unknown telephone bidderÔÇØ for $119.5 million. Thus, a great work of art that had been all but lost to us, hanging in a private Norwegian home for more than a century, made a brief public appearance and then was sold off to another private owner, probably to disappear for another 100 years. We will likely never see this work of art again in our lifetimes. The Scream is a part of art history and should hang in a public collection, probably in Norway, and not just decorate a California den or a dacha in the Ukraine, waiting to be fodder for the next auction. (Needless to say, no museum was in a position to spend that kind of money.)

Many asked why The Scream would go for this much money. Who the hell knows how these things happen? IÔÇÖd say the image is utterly iconic, as recognizable as the Mona Lisa or WhistlerÔÇÖs mother (or Damien HirstÔÇÖs shark). It looks and sounds and smells like the cusp of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It says, ÔÇ£I am a new psychologyÔÇöyour psychology.ÔÇØ The Scream has attained fridge-magnet status, and anyone who looks at it can at least say, ÔÇ£This is art-historical art.ÔÇØ I love The Scream because it shows Munch being modern without being Cubist, inventing Expressionism, exploring new ideas about color, composition, culture, society, cities, nature, drawing, and touch. We see a figure between worlds, suspended between earth and the unknown, wide-eyed, unable to hear us because his hands block his ears, even as he opens his mouth in a scream he canÔÇÖt hear himself. This is being inside and outside at the same time. The sky lights up; alienation blazes. ItÔÇÖs fabulous and prophetic. And, now, gone again.

Auction houses run a rigged game. They know exactly how many people will be bidding on a work and exactly who they are. In a gallery, works of art need only one person who wants to pay for them. Auctions jigger the rules in one tiny way: They have two people who want something, and they know how high each is willing to go. The setup is simple and perfect. The auctioneer simply waits until he gets around the ceiling he knows these two clients are willing to go to; then he pits the two bidders against one another. Voil├á! Money. Last night, Meyer knew that two people were ready to surpass $100 million. He got them there, said he had ÔÇ£all the time in the world,ÔÇØ kept them going up, waited for one to blink, and banged his gavel. Doing this publicly instead of in private just means that more people see what happened and want to try playing the game (not knowing or not caring that itÔÇÖs rigged). ItÔÇÖs advertising for the next auction: Whole new client markets open, and entirely new material now lures these players in. Now other Expressionist works at lesser prices will be put into play. And IÔÇÖll end up on the Charlie Rose morning show again, this time grousing about how much a Max Beckman is going to go for.

The bad magic here is that people can no longer see this work as a painting. Now people look at The Scream or Van GoghÔÇÖs Irises or a Picasso and see its new content: money. Auction houses inherently equate capital with value. The price of a work of art has nothing to do with what the work of art is, can do, or is worth on an existential, alchemical level. The closest I come to wanting out of contemporary art is when I look at the auction trade. A pox on their houses.