I never thought about the fabulously successful illustrator LeRoy Neiman, who died yesterday at 91. When I did think about Neiman, it was as a sort of Carnaby Street hippie-dandy who wore colorful clothes and made a lot of money. (His website says heÔÇÖs sold ÔÇ£approximately 150,000 of his silkscreen prints to individuals.ÔÇØ) He had a wide Dal├¡-esque mustache, smoked long cigars, and hung around the Playboy Mansion with Hef. He drew and painted boxers, tennis players, race-car drivers, Sammy Davis Jr., Liza Minnelli, Sylvester Stallone, Kentucky Derby horses, Bobby Fischer, and Boris Spassky playing chess on live TV, and Playboy Bunnies. I mainly saw NeimanÔÇÖs work incidentally, in the pages of my fatherÔÇÖs Playboys, furtively fumbling through for pictures of big American breasts. (Which might mean that LeRoy Neiman is a kind of unnamed fetish to millions of boys who grew up speeding past his illustrations to get to the good stuff.) His style was a mismatched gaudy mash-up of Abstract Expressionism, action painting, School of Paris painting, Raoul Dufy, George Bellows, Oskar Kokoschka, and familiar illustrational sketchiness, all done with a garish semi-psychedelic pop color and quick if sometimes sleazy slapdash splash.

Neiman, in other words, was not of the art world. We looked at him as a moneymaking illustrator. He knew it. And he didnt seem to care. (Which should have endeared him more to the art world.). He said, I can easily ignore my detractors and feel the people who responded favorably. (Which sounds a little like the way Jeff Koons talks.) Neiman was proud that my paintings and prints are in fine museums and galleries all over the world  [and in] films, TV programs, magazines, and books. It wasnt a lack of critical success that irked him: It was that he was too successful. His work, he said, attracts imitators and people looking to make a quick, dishonest buck. Some people try to paint in my style. Some simply sell pirated copies of my work. Some claim to be my publisher or agent or even my exclusive representative, when they are not.

Neiman was a closed ÔÇö even nonexistent ÔÇö book to me. Until 2009 when I met him and really liked him. That spring I gave the commencement address to Columbia UniversityÔÇÖs fine-arts graduates. Neiman was also there getting an honorary doctorate. Internally, I was being a wise guy, thinking ÔÇ£OMG! WhatÔÇÖs LeRoy Neiman doing on a stage? With moi?ÔÇØ Then as the commencement started, I read the program. I learned that heÔÇÖd not only given the school millions of dollars ÔÇö I was sitting not far from the ColumbiaÔÇÖs LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies, and had even taught thereÔÇöbut also that heÔÇÖd donated huge amounts of money to other art schools, organizations, and charities. And heÔÇÖd earned his fortune by making art rather than trading derivatives.

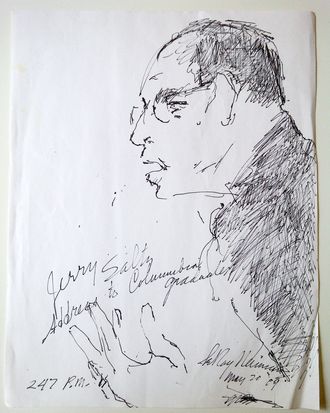

As I sat there and watched him looking up, over, and down, taking it all in, attentively drawing all the while, my ideas of him changed. I suddenly saw Neiman as an example of something IÔÇÖd just told the graduates that they might aspire toward. LeRoy Neiman was his own artist, someone whose style ÔÇö mishmash or not ÔÇö had mysteriously selected him. He then perfected it and took it as far as he possibly could, unashamed, with acceptance, joy, brio, experimentation, and boundless generosity. I knew I didnÔÇÖt like NeimanÔÇÖs art much more, but I no longer felt snide or cynical about it. Or him. As the ceremony ended, I looked for him. But he had grown tired and left early. Then his lovely wife, Janet, approached me. She said hello, handed me a piece of white paper, and said, ÔÇ£LeRoy wanted you to have this.ÔÇØ I looked down and saw a pretty dynamic sketch of me gesturing, leaning forward, speaking. It was titled Jerry Saltz Address to Columbia Graduates, and signed ÔÇ£LeRoy Neiman, May 20, 2009.ÔÇØ I melted.