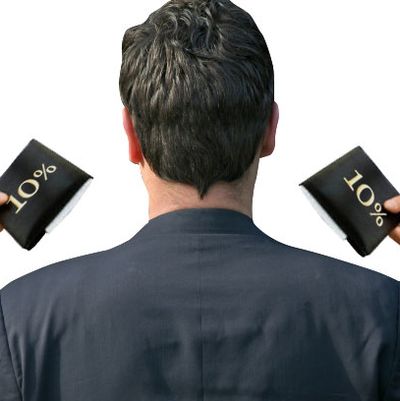

When I started as an agent in 1987, talent managers were most commonly thought of as appendages of musicians and a minority of actors. If someone said “manager” to me back then, I would have thought of Colonel Tom Parker, who guided the career of Elvis Presley for a reported commission of 25 percent (most managers today, like agents, take 10 percent). The majority of actors and practically all writers, directors, and producers only had agents, who not only found jobs and set up projects on behalf of their clients, but also were hand-holders and career strategists. Agents have a franchise, established by state law, which says that they can procure employment and negotiate deals, while talent managers, who are unregulated and solely provide career guidance, are technically prohibited from those actions.

Now it seems that almost all actors and a high percentage of writers, directors, and producers have managers, and those who don’t are thinking about getting one. The reason for this change can be found in the news reports written about talent agencies these days, most of which involve a cycle of mergers between agencies and the subsequent firings of suddenly superfluous agents. And the few remaining agencies are financially restructuring and making high-profile investments in side businesses, as ICM did in buying out a majority of their former owners and changing their name to ICMPartners, and CAA and WME did when they sold part of themselves to, respectively, private equity funds Texas Pacific Group and Silver Lake Partners. Whenever I read one of these stories, my first thought is, Great for the talent managers — because all of this distraction and job cutting only means that agents don’t have the time nor interest to be as attentive as they once were and that gap in the process of representation still needs to be filled by someone.

Though no agents would publicly acknowledge that they and their colleagues are less interested in their clients’ needs, speaking privately they often tell another story. One partner at a major agency explained it this way: “The two and two half-agencies that exist [CAA, WME, and the medium-size UTA and ICMPartners] are desperate to create an exit strategy, which means a salable asset, which means finding other businesses to leverage the core into.” With the agency owners looking to personally cash out, most of their companies are using the cash and clout they get from representing talent by making investments in other businesses: CAA has stakes in the online education company Encore Career Institute and social networking site Whosay, and WME has invested in social video site Chill. “Of course, we’re idiots,” continued the agency partner, “and don’t know anything about it, so it means a lot of distraction and meetings and New York. It is a goose chase. The agency owners are [no longer] interested in the combat sport to go out and get the data [as in, information on the status of studio and network projects] and use it to get jobs for the clients. For these guys on top, it is an incoming phone call and trying to move the offer to the next client if that one isn’t available.”

This situation, of course, creates an opportunity for managers to market their services to underserved potential clients. A former agent and now manager for writers and directors at a well-known management company tells me that she sells herself to potential clients like this: “A great manager turbo-charges representation … I don’t represent agencies, I represent clients … just like when I was an agent. Obviously in features that’s a no-brainer, but in TV the agency mandates the package first.” She’s referring to the long-running controversy in the business about agencies receiving an “agency package fee” for putting together a show or providing its key element. This fee is commonly equal to 3 percent of the license fee that the network pays the studio for the rights to the show, plus 10 percent of the profits, which can add up to a huge amount of money, possibly even more than what any individual client of the agency would make on the show. That the agency can make so much from jamming its clients together into a show creates the possibility of a conflict of interest; there’s a lot of incentive to advise a client to do a show that wasn’t in his or her interest, but that would be very valuable to the agency. “That’s great if an agency can do what’s best for their clients while having the resources to preserve their package … but you know how well that works,” she added sarcastically. Apparently, these ulterior motives are resonating with the talent, who are now left looking for objective advice. As this manager says, “Clients feel they need to have two people do for them what one used to do. It is a great time to be a manager who knows what they are doing.”

A department head at a big agency sees some value in managers but doesn’t always buy that they’re imperative. “Because agencies have consolidated into two or three big agencies, [clients] think they need managers to navigate things,” he says. “In my case, I’m really involved in my clients’ lives and it is the manager who has to play catch-up. Still, for filmmakers who are trying to break into the business, it can be effective [to have a manager]. They can help them practice a pitch and figure out what to say in meetings.”

Though there may seem to be an adversarial position that has developed between agents and managers, the situation is more symbiotic than it appears, and both sets of representatives have benefited from the new order. The agencies, faced with declining revenue from their clients as salaries for creative talent has dropped, have followed the path of other businesses in similar circumstances: cut overhead by cutting personnel. Another agent turned manager with his own company points out that, “when Endeavor merged with William Morris to make WME, they took on around 250 more clients for TV and kept only three WMA agents, letting go over 100 reps and support staff: UTA signed 60 former William Morris clients who didn’t stay after that merger and kept one agent who has since left.” Obviously, the increase in the client-to-agent ratio benefits the bottom line of the agency; but, at the same time, the client is receiving worse service for the same 10 percent he paid before.

And where do many of these jobless agents end up? Ironically, as managers, often representing the same people whom they repped when they were agents. In effect, the agency has off-loaded the cost of extra career guidance for an individual client by getting that client to pay for that service directly with an additional 10 percent fee. And though the managers act like they’re now protecting their clients from agents’ self-interest, they also can be co-opted by their own interests. Says the agency department head, “The dirty little secret is the reciprocity that goes on between agents and managers trading clients, and doing favors for each other.” History shows that managers who deliver clients to an agent usually get other clients delivered in return. “The most corrupt thing is when [a producer] wants a client of a manager and can’t have him unless he makes [the client’s] manager a producer on the project. And the agency supports this.”

As the owner of a restaurant, I would love to save money by firing the dishwasher and dumping all of the equipment necessary to keep plates and utensils clean; then the unemployed dishwashers could stand outside the restaurant and rent clean plates to customers for a separate fee. I could then still charge the same prices and increase my net profit, while the dishwashers would probably make more than the minimum wage they are getting now. Unfortunately, there is too much competition and customers would just go elsewhere for meals where the plates are provided for free. The talent agents are lucky in that they have rolled up so many of the agencies into two giants and two medium-size companies that there isn’t real competition and they can get away with their machinations with little or no blowback. When I asked the manager with his own company why the talent puts up with this state of affairs, he offered, “I think the individual clients are experiencing fear and lack of choice.” This is understandable: It is a small business and for an actor, writer, or director, the idea of standing up to the entire agency business and saying, “Hey, do your job as you are supposed to for the fee that has been standard for a hundred years” seems impossible and potentially damaging to one’s career. And the government has too much on their plate with regulating banks and oil companies to bother with talent agencies.

But here is the good news: When businesses overconglomerate to the detriment of the consumer of their products or services, the result is usually the formation of new small businesses intent on picking up the dissatisfied clientele tied to the companies who swallowed, digested, and excreted parts of their former competitors. This environment looks great for boutiques like the Ilene Feldman Agency, which represent actors like Ryan Gosling and Chris Hemsworth, and Verve, which represents a long list of up-and-coming writers. I predict more small agencies starting up in the near future and offering more and better service for their clients, as well as a good living for the owners of those agencies. Until, of course, their eventual desire to keep growing their profit margins and clout leads them to join together to form larger agencies that can sell parts of themselves to private equity firms and generate big payouts to the owners of those agencies and worse service to their clients. And when that happens, it will be great for talent managers, again.