People keep talking about Red Hook Summer as a return to your roots. Do you feel that way?

I am glad you asked that, because I am going to try to shake the narrative as much as I can. This is not Spike going back to his roots. Red Hook Summer is another chapter in my chronicles of Brooklyn. I am a professor at NYU—I’ve been one the last fifteen years—and one of the courses they are teaching in cinema studies this summer is “Scorsese’s New York.” The postcard has a map of Manhattan and a dot where each Scorsese film took place. For me, it’s Brooklyn. She’s Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing, He Got Game, Clockers, Crooklyn, and Red Hook Summer.

The movie has a lot of Carmelo Anthony.

We actually painted the shrine to him on the courts for the movie. It’s still there.

There’s a perception that Carmelo isn’t really from New York, that he’s really from Baltimore. But the people of Red Hook don’t feel that way.

They claim him. They claimed him when he was at Syracuse. We claimed Michael Jordan—he was born in this neighborhood, Fort Greene.

But here is the genesis to the whole thing: When the Knicks traded for Carmelo, he got a deal with Boost Mobile, and they came to me to do a digital piece on Carmelo. So I said, “Let’s go to Red Hook.” Then, one Saturday morning, [co-screenwriter] James McBride and I were eating breakfast at Viand. Do you know where Viand is?

I do not.

It is the best coffee shop in New York. It is on 61st and Madison. One Saturday morning, James McBride and I were eating breakfast there. We both have kids, and we were talking about what kind of film our kids would see. One thing led to another. I talked about Red Hook, he grew up in Red Hook, his father and mother were preachers, you have the Carmelo thing, and that is how it all came together.

Besides writing and directing, I am producing this thing, too, so I know that time is money. The film was shot within a ten-block radius. We shot it in eighteen days, three six-day weeks. She’s Gotta Have It was shot in twelve days and two six-day weeks.

Is that as quick as you had shot a film before this?

I do not know if you can shoot it faster.

Is it more fun to do it quick and dirty?

No. Fun is not for me determined by whether it is an independent film or Hollywood. From the very beginning I have done both. I am a hybrid. I do independent films and also do Hollywood films—I love them both. But I knew the Hollywood studios were not going to make this film. And that is not an indictment of them, it is just a fact.

Red Hook Summer had a somewhat difficult reception at Sundance. Did you edit it at all since then?

We changed it. I forget what we did—whatever we had to do to make it a better film we did. It was nothing unusual, just the same processes as an editor on a book or a musician doing an album—twenty songs and you have to get it down to twelve.

You brought Mookie back from Do the Right Thing. He’s still delivering.

And his pizza is never cold.

But this isn’t Mookie’s Brooklyn anymore.

It’s so different. But it’s all different. There’s gentrification of Cobble Hill. Fort Greene’s gentrified, Harlem was gentrified, Bed-Stuy’s gentrified, and Williamsburg is gentrified.

People lived on the Lower East Side and got priced out of there. Then you moved to Williamsburg—oh, it became too hip. Now they are going to Bushwick. What is going to happen to Bushwick? Next thing, after Coney Island, there is the Atlantic Ocean.

Only Staten Island will be left.

I’m sure that will be the last resort.

I live in Cobble Hill, where you grew up, and it’s so gentrified now that it’s almost entirely white people with strollers like me.

Where are you from?

Well, I’ve lived in New York for twelve years, but I am originally from Central Illinois.

I am trying to detect your accent.

It took me a long time to get rid of it, to be honest.

You did not get rid of it.

I cannot imagine what it must be like for you to walk around Cobble Hill now and see wheat-germ places and Pilates.

That does not bother me. What bothers me is that these kids do not know the street games we grew up with. Stoop ball, stickball, cocolevio, crack the top, down the sewer, Johnny on the pony, red light green light one-two-three. These are New York City street games.

How long did you live in Cobble Hill?

Eight years, from ’61 to ’69. I was born in Atlanta, Georgia, but we moved here from Atlanta at an early age. First we lived at 1480 Union Street in Crown Heights and then we moved to Cobble Hill, 186 Warren Street, between Henry and Clinton.

We were the first black family to move into Cobble Hill. And we got called “nigger.” At that time, Cobble Hill was strong—I mean, strong—Italian-American, because of the docks. But as soon as the neighbors understood that there weren’t any other black families, it was not like a mass of black families moving in behind me, I was just like everybody else. It was a great time to grow up in Cobble Hill.

Do you make it back at all? It’s not so Italian anymore.

I know. It is Brooklyn Heights now. But when I was growing up, the demarcation line was Atlantic Avenue. Brooklyn Heights was rich, Jewish. Atlantic Avenue was like the train tracks, and on the other side of Atlantic Avenue was Cobble Hill. It was mobbed up. When you crossed Atlantic Avenue, that was like going to another world.

They say that [Brooklyn Heights private school] Saint Ann’s was formed because parents did not want us black kids in their schools in Brooklyn Heights.

Do you feel like your education was adequate?

I had a great education. From kindergarten to John Dewey High School in Coney Island, I am public-school educated. When I went to school, you had to take art, you had to play an instrument. You had to play an instrument. But it’s all degraded since then. I do not know what kind of nation we are that is cutting art, music, and gym out of the public-school curriculum. We are going to be a nation of young students who are obese, know nothing about art, know nothing about music.

I am very fortunate I can send my kids to private school, but everybody does not have the money. If you cannot get your kid in a good school today, your kids are going to be behind the eight ball.

Education seems really important to you.

I feel like I should talk about public education all the time, but maybe you can’t do enough. I just think that it goes across the board—housing, education, health care. You got to have affordable housing. They got to make the public schools better. This goes across all races—this is not a black and white thing. New York City cannot just be rich. It will lose its entire flavor if it is.

Back in the day, if you were broke, you could still get by in New York. There are always going to be rich people, but you used to have more diversity. And this is something that is happening in this country: the haves and the have-nots. That is not a good situation, when the have-nots see what the haves have and the haves are not giving it up.

Wasn’t that divide always here?

It is more pronounced now than ever. Because people are making more now than they have before. You had a million dollars back in the day—that was some money. Not today, man. You got a million dollars, that’s just the down payment.

Do you think part of it is because New York is seen as a more desirable, safer place?

We will not go into stop-and-frisk with my man Raymond Kelly.

I would love for you to get into that.

Look, there are pros and cons. Is it safer than it was back when Scorsese made Taxi Driver? Yes. But a lot of people liked 42nd Street better the way it was. New York City, I feel, is the greatest city in the world, but it will not be that anymore if it is only rich people here. And people want to stay here, but they cannot afford it. People have to be able to feel that they can afford to live here and their children get a good public-school education.

And be safe.

How safe you are in New York depends what neighborhood you live in. Now I would tell you, sir, the Upper East Side is more safe than Brownsville, Brooklyn. The Upper East Side is more safe than East New York.

Is that why you moved up there?

It had nothing to do with safety; it had to do with my wife wanting us to get out of Brooklyn.

Why?

Because everybody in Brooklyn knew where I lived, and they were ringing my bell—a lot of times at three and four in the morning when I was out of town, and she couldn’t take it no more.

How long ago did you make that move?

Fifteen years ago. First we lived at the corner of West Broadway and Spring, and that was insane. On the weekends, you couldn’t even walk the sidewalks.

So you live on the Upper East Side, but you commute down here to Fort Greene every day?

Every day.

Your offices are three blocks from the Barclays Center. Do you think the Nets will change Brooklyn?

I am happy for Brooklyn, but I’m not leaving my beloved orange and blue. And I just cannot wait. One of the biggest nights in New York City sports history is going to be the first Knicks-Nets game in Brooklyn. That is going to be huge. That is going to be war.

What do you think of the stadium?

I do not know the specifics about how people got moved out and all that stuff. I’m not going to get into the politics of the Barclays Center; the thing is, it’s up, it’s a reality, and that’s just that. It’s here; you have to deal with it. Negative and positive; I can deal with it. Jay-Z is going to christen it in September with his concert: you’ve got Barbra Streisand coming. The Nets will be playing there in the next NBA season, and Brooklyn has their first major-league team since the Dodgers fled after the 1957 season, the year I was born.

But I do know this: I just hope people take mass transit. I hope they take it when they are coming from Long Island, because you know you have the Manhattan Bridge and you have the Brooklyn Bridge. The Manhattan Bridge comes [begins drawing on a napkin] … If you come up the bridge right on Flatbush Avenue, you come off the Brooklyn Bridge, you make a left on Tillary, and you are on Flatbush Avenue. Flatbush and Atlantic is the Barclays Center. I predict traffic is going to be so jammed that you are going to be on Canal Street in Manhattan trying to get over the Manhattan Bridge. It is going to be crazy. People have to use public transportation.

Here is the thing, though: Here goes the Barclays Center [begins drawing on another napkin], so people can walk. All right, where we are, when you go out of here and you go straight down here, you see the Barclays Center, so people can walk from Fort Greene without taking public transportation. You can walk from Park Slope, you could walk from Cobble Hill, and you could walk from … what is after Cobble Hill?

Carroll Gardens. Boerum Hill?

The Heights, too. So there are like seven neighborhoods that people can walk from. That’s a lot to draw from. The Barclays Center is going to be crazy.

I do not have nearly the Garden history that you do, but Linsanity was as crazy as I have seen the Garden.

That was as loud as I have ever seen the Garden. D’Antoni as an act of desperation said, “You go in.” The Lakers game, that was bananas. What I love was that Sports Illustrated cover where Jeremy Lin is going down the lane and he is surrounded by five Lakers and he is the only Knick on the cover. There are five Lakers converging on him, and he made the layup, too.

I never thought that his being Asian was the primary reason for the love for him, just one of them.

That was a factor. To say that is a factor does not make you a racist. What is the guy on the Rockets?

Yao Ming.

When you are seven-seven, I do not care who you are, you are a basketball player. But Lin, he went to Harvard and got cut twice. He got cut from the Houston Rockets on Christmas Eve.

Were you sad to see D’Antoni go?

Yeah, it was sad. Most of the time I am not happy when someone gets fired. I will probably find out, now that the season is over, what actually happened.

It seems to be somewhat Carmelo-related. There is an argument that, as great as Carmelo is, he has too much power now.

Too much power? Any star on any team in the NBA has some weight. That is just the way it is.

But can you see the Knicks winning a championship with Carmelo?

Yeah, if we get the right pieces.

I interviewed Tyson Chandler right when he got here, and he said, Every single time that I have ever played here, Spike Lee would bother me—bother me in a good way. So can you get Ray Allen here?

Ray Allen—he is going to be a free agent?

Yeah.

I got to get a list of free agents.

Then will you get to work?

Look, I know there are people who think I work for the Garden. I do not. I do not work for the Garden. I just want to see another banner from the roof. I am tired of looking at the ’69–’70, ’72–’73 banners. That is a long fucking time.

How much are your tickets? Can you say?

It is public knowledge. I try not to remember the price, but it is a fortune.

Was there ever a time when you thought maybe it is not worth it this year?

I momentarily had those fleeting thoughts, but I am happy now.

What do you think of Bloomberg?

Fellow New York Knicks season-ticket holder.

And politically?

I think that his legacy took a blow his third term. In America, whether it be sports, politics, or whatever, people do not want to go out when they are on top.

What do you think of the soda ban?

I’m in favor of it. Look, when I was growing up in Brooklyn, we had gym, and you had to run. You had some physical activity. Children today in public schools across the country are not being taught art, are not being taught music, and they have no physical ed. Obesity is a major, major problem in this country. Americans—we’re just obese. It’s crazy. Ask African-Americans. We are way over index on obesity, which means we are over index on diabetes, heart disease, and it goes down the line.

How do you think President Obama is doing?

I support him; my wife and I gave a benefit for him at our house. But I think this election is going to be close. Bottom line, there are many people in America who look at themselves and say, “Am I better now than I was before?” It is going to be tooth and nail, and I think it is going to get nasty. But, in my opinion, if they are trying to bring up Reverend Jeremiah Wright again, they are really reaching. I hope and pray that people are not going to go for the Willie Horton okeydoke.

Do you think people will?

I got faith that they won’t. Honestly, though, the big question is, I think there will be a block of people saying, “I cannot vote for a Mormon.”

Are those people voting for Obama instead? That seems unlikely.

They got a tough decision: Obama or a Mormon. Their beliefs got them between a rock and a hard place.

What do you think of Romney?

You know what’s funny? I met him in an airport, Reagan National Airport, and we said hello. It was, like, two, three years ago. I was just in D.C. and he was there and he said, “What’s up, Spike?” and I said, “What’s happening, Mitt?” We were in line getting something to eat. So I said what’s up and shook hands. I think it is going to be very, very, very close.

One of the things that helped Obama win last time was the enthusiasm and turn-out-the-vote efforts among African-Americans.

Wait a minute, wait a minute. It wasn’t just African-Americans.

Of course.

I think really people forgot about this; it was a coalition of many different groups of people that got President Barack Hussein Obama elected. It was not just—that’s the whole thing, it didn’t just go on the black vote; it was a coalition.

But many people, black and white, went for the okeydoke and believed that racism was eradicated from America the moment he got elected. Like it was presto-chango, abracadabra, whiz-bam, or whatever you want to say. Poof, and it is gone. And I think that was naïve.

On Election Night, I was at a party in which this group of cynical New Yorkers literally started singing the national anthem unironically.

I am not going to hate on that—it was a great moment. It was one of the greatest moments in American history, and people really felt that moment. I think all those emotions were honest—black, white, and brown. People would cry, and some in disbelief, some in joy, some in euphoria. America had reached a point that many people, black and white, thought would never, ever, ever, ever happen. And this was the epitome of how great we are as a country, and the world saw that.

The world saw that, and the world looked at America like they had not seen America since World War II. Since we kicked the Fascists’ ass with Italy, Japan, and Nazi Germany. That was the last moment that the rest of the world looked at us like that, I think.

Where were you?

I was there. I was not going to miss that. I was right there in Grant Park, my brother and I. We would have walked to Chicago if we had to.

Do you think that sense of historical moment would diminish if Obama lost?

Maybe. Not to me. But to some.

Do you think if he does lose we will see a black president again anytime soon?

I will be dead before it happens.

There is a lot of talk these days about the parallels between gay marriage and civil rights. Do you think that’s valid?

All I can say is, I support gay marriage. They want to marry each other, I support it. That is their choice. And they are going to write a book about the vice-president.

He sort of made that happen.

It is funny, my wife and I, we had an argument. I said, “You know what? I do not think he was supposed to do that.” I said, “I think he came out of pocket on that.” She said, “No, no, they set it up.” I said, “Uhn-uhn. Crazy Joe.”

Is the parallel with the civil-rights movement valid?

It is the same thing—I guess it is the same thing. But here is the thing, though: All these movements and groups of people who have benefited from the civil-rights movement, I think they should have to take a pledge. Okay, you want to get married to each other, but then you cannot go around and act this way against other groups of people, because some of those groups made it possible—laid down the foundation.

I do think that is a generational thing. I was born in 1975, and it is hard for me to imagine some of those horrors ever happening, so for me it is just a forward march of progress. You hear people say this a lot about gay marriage: We do not have to worry about the laws now; people will just go toward freedom and go toward equality.

That same rhetoric was used by the segregationists who were telling Dr. King, “You are moving too fast, this stuff has to take time.” Dr. King was like, “Hell, no. We got to do this now.”

I might not be saying it right, but I just hope that people honor the foundation of the civil-rights movement in everything they do. Know the history. Do not think this just came out of the air. Four girls got blown up at the 6th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Medgar Evers, we can go down the line. Just know the history.

Years ago, you argued that Norman Jewison shouldn’t be directing Malcolm X, that it should be a black man. Now we have Quentin Tarantino making Django Unchained, a film about slavery. Have you read the script?

Someone tried to slip it to me, but I did not read it.

Would you have any concerns? Have you come around to him as a filmmaker?

Have I done what?

Do you like his films?

We are just two different people. We just have two very different views on how we see the world. There is room for both.

Have you seen the trailer yet?

Nope.

Will you watch it?

I’m not commenting on Quentin Tarantino or Django.

It does seem like you feud with other filmmakers a lot. You criticized Clint Eastwood for not having more black soldiers in his World War II films.

I was not saying it for myself, though. I had been in dialogue with black Marines who were there. Clint Eastwood was not the first to whitewash war, either. People of color have a constant frustration of not being represented, or being misrepresented, and these images go around the world. There are exceptions with, like, Laurence Fishburne in Apocalypse Now, Forest Whitaker in Platoon. The first person who died for this country in the American Revolution was a black man. Crispus Attucks was the very first one. From the Civil War, you can probably put Glory in there.

Though, of course, that was told through the eyes of a white character.

Yeah, that’s a whole other thing, but we’ll let that go for now. But there has been a total omission of the contribution of African-Americans in the defense of this country for democracy. It’s crazy. George Lucas—George freaking Lucas—had been trying to make Red Tails for twenty years, and no studio would make it, so he goes off and says, “I am going to finance this one myself.” Even George Lucas can’t get the film made. What did they tell him? “We do not know how to market this.” I am not making it up. People would not even show up to the screening. That is where the frustration comes.

What frustrated me about that Clint Eastwood thing is, if you do not say something, is there a more prominent name that is going to? You sort of have to. But when you say it, the public is like, “Oh, there goes Spike Lee. There he goes again.”

You sound like my wife.

The era when you came up seems like a much brighter, more adventurous time for black cinema than today. Back then you had John Singleton nominated for an Oscar, and the Hughes brothers, and you. Now Singleton is directing Taylor Lautner movies. That’s amazing.

I have never spoken with John about that, but I do know that he just wanted to work.

Would you do a Taylor Lautner movie?

It has fortunately not come to that yet. No disrespect to John.

But film actors want to act, and directors want to direct. And that is something we all deal with, unless you’re Spielberg, Lucas, maybe Cameron. Those three are the big three. They get to do what they want.

It still doesn’t change the fact that black cinema is worse than it was twenty years ago.

There was more variety of subject matter back then. I think it showed more depth to the African-American experience. Hollywood can make a certain type of film when it comes to black folks. Like, Think Like a Man. That film made a ton of money, so I know that they are probably writing the sequel at this moment.

Kind of the Tyler Perry syndrome.

I would not call it a syndrome. Thing is, those box-office numbers prove there is an audience for those films. Yet, at the same time, I think there is an audience that would like to see something else. At this moment, those other films have to be made outside the Hollywood studio system. This comes down to the gatekeepers, and I do not think there is going to be any substantial movement until people of color get into those gatekeeper positions of people who have a green-light vote. That is what it comes down to. We do not have a vote, and we are not at that table when it is decided what gets made and what does not get made. Whether it is Hollywood films, network or cable television, we are not there. When I first started making films and I would have Hollywood meetings—and I know this for a fact—they would bring black people out of the mailroom to be in the meeting.

That doesn’t still happen, does it?

I do not know. But I will say the best chance of me meeting somebody of color is the brother man at the gate who is checking to see if I am on the list.

Sports is years more evolved than Hollywood. Decades. The great thing about sports is, you have to produce. Jackie Robinson, Joe Louis, Jesse Owens, they set the gauntlet down, and people said, I may not like black people, I may only like this person, but if they can help me win, I will take it. You have to produce in sports.

But if it is really just a matter of producing, why isn’t there more representation?

Here is the thing, Will: I made a vow to myself, I am going to stop answering on behalf of the studios. Because every time something happens to black people, the L.A. Times is calling me up. And I say, “You have to speak to the studios.” And he says, “They will not go on record.” I say, “Well, I cannot help you. I cannot speak on behalf of the studios about why they make the films they make.”

This is kind of what Bamboozled is about. Black images in film, or the lack thereof. Of all your films, I feel like that’s the most intentionally provocative.

And I understand that. At the end of the film, we have the whole roll call of those images, which were based on the dehumanization of black people, human beings, throughout the history of Hollywood and TV. Even Bugs Bunny. It was an indictment. Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney. You can go down the line. I did not make that stuff up.

Do you still see that sort of minstrelsy in the post-Bamboozled world?

Well, in the post-Bamboozled world, it is not just about African-Americans; everybody is willing to do whatever to be on TV. This reality TV has changed everything.

Do you watch much television?

Not reality TV.

Do you think it is making people dumber?

It sure isn’t making us smarter. It is putting some money in some people’s pockets, but I do not think it is making the world a better place. That would be my statement on that.

It’s striking, looking back on your career, how much you’ve always been in the public eye, even as a small independent filmmaker. As a point of comparison, Jim Jarmusch, a contemporary of yours—he never became a personality outside his films.

Jim is my man.

I am not criticizing him or you.

Jim has not had the output, so that is something that you have to take into account. And when Stranger Than Paradise came out, he was the poster boy.

Yeah, but no one in Illinois knows Jim Jarmusch. They all know Spike Lee.

Here is the thing, though: What made my circumstance different is that, No. 1, I was in my films in the beginning. And then, No. 2, the character I played in She’s Gotta Have It, Mars Blackmon, was paired with Michael Jordan in one of the most successful ad campaigns ever.

You were 31.

At that time, people were watching games and seeing me. They didn’t even know where that character came from or that I was a filmmaker.

What was Michael Jordan like at that age? It was before everything for him.

What do you mean, before everything? He was Jordan. He was Jordan then.

Me and him were friends at the beginning, and we’re still close friends to this day. An important thing that people really don’t know is that Nike came to me, but I still had to go to Michael for approval. At that time, Michael had not heard of me, and he had not seen my movies. In fact, I had never directed a commercial before. He could have put the kibosh on that right away and said, “Look, I can’t chance it; I can’t risk it. Let me go get some big shots on Madison Avenue.” I’m always grateful to Mike, because he didn’t do that, and he gave me a shot.

He seems a lot more risk-averse now. This was the guy with the famous line, “Republicans buy shoes, too.”

I’ve never asked Michael about that comment, but I will say—and this is how to answer this question, y’all—everyone has said something they would want to take back. That’s how I’m going to answer that question.

Talking to you today, I can’t help but think you have mellowed somewhat—you’ve passed on lots of opportunities to comment on things.

Have you seen Red Hook Summer?

I have.

If you’ve seen that film, why would you ask the question, Am I trying to play it safer?

I’m not talking as a filmmaker.

What are you talking about, then?

There is a perception of you that you like being controversial.

The stuff I have done and said has never been for—and this is a word I really detest—controversy. I think the word is misused. I was raised in a household—we were all encouraged by my parents to speak your mind. Now, that does not mean you should speak every time there is an opportunity to. And so it has been a learning experience over the years that, even before this Twitter thing, I said, I cannot talk about everything. I cannot do it. I cannot do it, cannot do it.

Yes, that Twitter thing—when you retweeted the wrong address for George Zimmerman and it turned out to be an elderly couple.

They are great. The McClains. But that was not a good time. A big mistake on my part. Not a good time.

Are you more careful about what you say now than when you were younger?

I think I am smarter—I feel I am confrontational when I have to be, but it is not something that I live, breathe, sleep, and eat. There are just some things since I have been a filmmaker that I have made a comment on, and when you stick your neck out there, you got to let the chips fall where they may, and every time is not going to be perceived the right way. You are going to be misquoted, misjudged, or whatever, but this started early. Joe Klein said Do the Right Thing was going to incite riots.

In New York Magazine, actually.

Your man did me, you know. Like, this is going to hurt David Dinkins’s bid to be the first African-American mayor. I remember this one line: Opening this weekend, “in not too many theaters near you, one hopes.” So it is not new.

And now the president says it’s the film he took his wife to on their first date.

Yeah, I’d say Joe Klein maybe had that wrong.

It must be pretty amazing that Obama took Michelle to Do the Right Thing.

When he was sizing Michelle up, this fine woman, he said, “How am I going to impress her?” I always kid him, good thing he didn’t choose motherfucking Driving Miss Daisy or she would have dumped his ass right there.

Do you think about legacy?

Well, my No. 1 legacy is going to be through my children. My daughter, Satchel, and my son, Jackson, [who] is going to be 15 tomorrow. They both are definitely going to do something in the arts. And they are going to be successful, too. I know they are going to be the best legacy that my wife, Tonya, and I leave behind.

Do you ever feel this Spike Lee–ness, people’s gut reactions to you, has overshadowed your work?

Oh, I know that for sure. I just read the people’s reviews. When I read a particular review and it is talking about the Knicks and me yelling at a ref …

Reggie Miller shouldn’t come up in a movie review.

I was on the cover of Esquire magazine for Malcolm X. You know what the cover title was?

I’m afraid to ask.

“Spike Lee hates your cracker ass.”

Was that a quote?

No, it was not a quote.

Would it have been easier or harder to get as many movies made as you have gotten made without being Spike Lee, rabble-rouser?

Oh, it would not have been easier, it would have been harder. Spike Lee is a brand. Even to this day.

* This conversation has been condensed and edited from two interviews, conducted on May 5 and June 13.

This story appeared in the July 16, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.

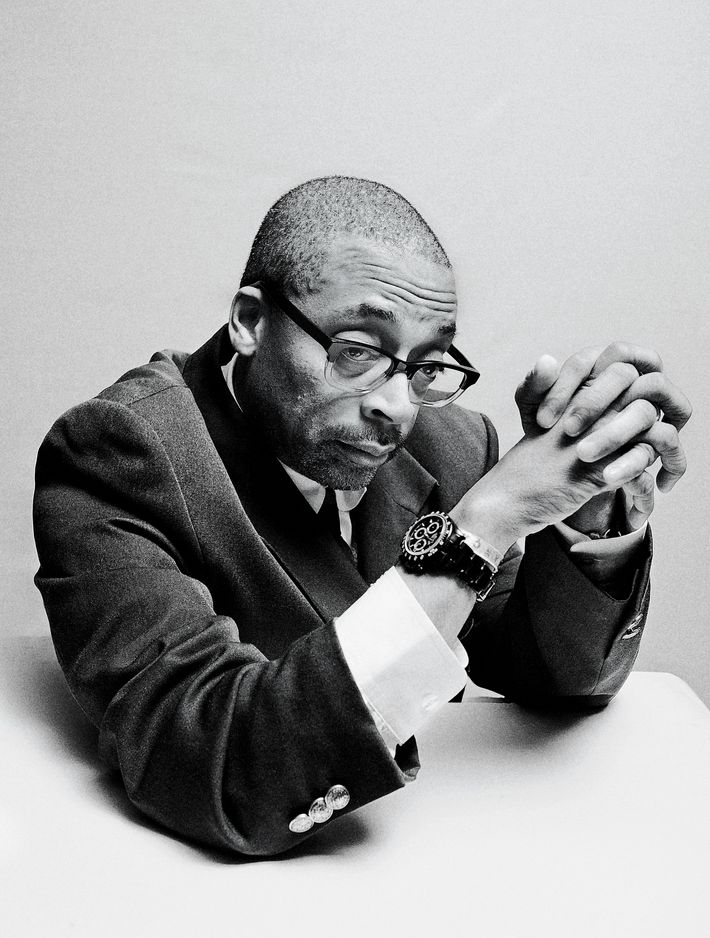

Returning to Brooklyn—a very different Brooklyn—with Red Hook Summer, the outspoken filmmaker talks with Will Leitch about the timidity of Hollywood, reality-TV minstrelsy, and what it’s like to have inspired the president and the First Lady’s very first date.

When I was 13, I had a picture of you and Michael Jordan on my wall.

The poster where he was holding my head up?

That’s the one, from your Nike commercials with him. Five years after that, you were making Malcolm X. No offense, but I’m not sure you could get Malcolm X made today. Did you have more power then?

I do not think the word is power. I think that it is a different climate today. I do not think Oliver Stone gets JFK made today. Unless they can make JFK fly. If they can’t make Malcolm X fly, with tights and a cape, it’s not happening. It is a whole different ball game. There was a mind-set back then where studios were satisfied to get a mild hit and were happy about it; it helped them build their catalogues. But people want films to make a billion dollars now, and they will spend $300 million to make that billion. They are just playing for high stakes, and if it is not for high stakes, they figure it is not worth their while.