Thus far, the three most important moments in the four-plus-season run of Breaking Bad involve cancer. They are:

1. The moment in the pilot when Walt learned he had cancer and began cooking crystal meth, ostensibly to pay for his treatment and take care of his family, but really to kill his inner schmuck and replace him with Heisenberg, a.k.a. the Danger, a.k.a. the One Who Knocks.

2. The sequence near the end of season two wherein experimental medical treatment sends Walt’s cancer into remission at the same time that his criminal actions set off a chain reaction that makes jets collide over Albuquerque.

3. Walt and Skyler’s face-off in last night’s episode, the climax of which found Skyler, in rebellion against Walt at last, admitting she was “a coward” who lacked Walt’s dark “magic” and that her only option was to wait “for the cancer to come back.” Every cigarette Skyler smokes is another wish for her husband’s destruction. If the series were religious, you could call them burnt offerings. Slang for cigarettes: “Death sticks.” “Coffin nails.”

Walter White doesn’t just have cancer. He is cancer.

His cancer diagnosis doesn’t just describe a physical illness. It’s a metaphor for the evil inside Walt: the mix of arrogance, greed, intellectual vanity, and male insecurity that drove him to kill the old Walt and replace him with Heisenberg. It was always there, even if others, including Walt, couldn’t see it. (Some, like Hank and Marie, still can’t, because Walt used to be harmless and still remembers how to fake it.)

As long as the vileness stayed inside of him, Walt was a danger mainly to himself. His decision to cook crystal meth released the darkness into his household, his school, his city, the American Southwest, and parts of Mexico — a metamorphosis made official in that astounding cancer treatment/midair collision sequence — and it has been metastasizing ever since. He’s public enemy No. 1 right now: a meth kingpin and mad bomber on the loose in New Mexico. When Skyler wishes for Walt’s cancer to return, she’s wishing for her husband’s death, but she’s also wishing for the moral cancer to be driven out of the world and contained within Walt, like a genie stuffed back in its bottle.

That’s bound to happen eventually, because Breaking Bad is not a study in moral relativity or ambiguity. It’s a science-minded show that examines good and evil actions in context of Newton’s laws of physics: action and reaction, impact and collateral damage. That leads to this, bing, bang, boom, everything is different, and watch out, duck, it’s coming back to hit you in the face.

If Walt were to suddenly address the viewer and ask, “How did this happen?” you could reply, “Well, it all started here,” and show him the scene in the pilot where he presses Jesse into helping him cook. On Mad Men, as on The Sopranos and Six Feet Under and other precursor dramas, people change over time but can’t figure out exactly how or when they changed. Breaking Bad characters don’t have that problem unless they’re insane or (like Walt, and to a lesser degree, Gus Fring) deluded by vanity. They can look back over the timeline of their lives and identify the pivotal moments that set them down whatever path they’re currently on. The show’s writers map their moral progress like Hank laying out the Los Pollos Hermanos/Madrigal case in a cork board mosaic of photos, captions, and connecting lines. (The show it most resembles is The Shield, another pulpy melodrama about people committing moral suicide in increments.)

- Skyler used to be a law-abiding citizen, a loving spouse, and an example to her son. Now she’s an accessory to murder, assault, drug dealing, tax fraud, and money laundering. And she’s a prisoner in her own home, plotting to destroy her husband and free their kids from his influence.

- Poor, dumb Ted Benake is paralyzed because of Skyler, and because he flouted basic business ethics and failed to appreciate the incredibly risky financial gift that Skyler gave him via Walt’s crawlspace nest egg.

- Jesse used to be a small-time dealer, flaky but not dangerous. Now he’s a meth mogul and murderer whose soul is being polluted by Walt. Jesse might not have fallen so far if Walt hadn’t permitted Jesse’s overdosing girlfriend Jane to die choking on her own vomit. Jane’s death destroyed her air traffic controller dad, causing a midair collision that rained debris on Albuquerque homes and cars (including the Whites’) and plunging Jesse into a deep depression that enables Walt to “save” him, then manipulate him further.

- Walt’s evil has even upended the life of the show’s toughest, smartest criminal, Mike. He used to have a secure job with Gus. Now he’s scrambling to pay off Gus’s former inner circle, people whose silence would have been assured if Walt hadn’t murdered Gus, destroyed his business, and attacked a police evidence locker with a gigantic electromagnet, inadvertently revealing financial secrets that Gus had hidden in a photo frame. And on top of all that, Mike has no choice but to go into business with the man who ruined his life. I’d be surly, too.

- Walt’s actions in season two sparked a rampage by the Cousins that ultimately landed Walt’s brother-in-law Hank in a wheelchair and turned Hank’s wife Marie into his stressed-out nursemaid. And yet, perverse as it may sound, Hank’s journey is ultimately an example of positive change coming from trauma. Look at how he’s behaved since he returned to work, then compare it to Hank’s scenes before the shooting. He’s lost most of his bluster. He’s more observant, a better listener, and seems to have lost most of his arrogance. He’s smoother. He has gravitas.

This, more than anything else, makes me think it’ll ultimately be Hank who catches or trips up Walt: There’s an odd but pleasing symmetry to their stories. Walt, perhaps more than anyone else, created the new Hank by drawing the Cousins to Albequerque. Hank’s transformation-by-trauma from a pretty good cop into a great detective and leader of men is a light-magic mirror of Walt’s mutation into Heisenberg.

And as I typed that, I suddenly remembered that Hank is the one who originally planted the idea of financial-salvation-through-meth in Walt’s head, way back in the pilot. Throw a rock in a pond, watch the ripples spread.

Almost everyone Walt knows is demonstrably worse for having known him — even Saul, a once comfortably corrupt lawyer who’s constantly on the verge of having to go into hiding, and Walt Jr., who’ll learn the truth about his pop eventually. The nebbish turned gangster has spread so much chaos and misery over the last four-plus seasons that his rampage simply can’t continue. This is not a moralistic statement, even though I hate Walter and would love to see him die, just as I wanted to see Iago punished. It’s a prediction based on what I think is the show’s worldview and M.O. I don’t think it’s headed for sixties European-art-cinema–style obfuscation — i.e., a Sopranos ending — because that would be out of character for a show so obsessed with narrative and moral accounting. According to laws of probability as well as rules of drama, order will be restored eventually — if not by Hank or Skyler or Walt Jr. or Jesse or some other supporting character, then by Walt’s preening arrogance, his mistaken belief that he’s a god among men.

The show foreshadows Walt’s downfall in the scene following Skyler’s cancer threat. Walt is pictured from behind, a faceless brain looming over his hunched shoulders. Then he accidentally nicks himself while shaving. The soundtrack music suggests a tolling bell.

The episode ends with a close-up of Jesse’s belated birthday present to Walt: a wristwatch. I don’t think Jesse’s watch gift is secretly a bomb — we’ve seen no evidence that Jesse knows how to do that, and though he might be in cahoots with Mike, explosives aren’t Mike’s style (he’s a hands-on guy). But there might be a tracking device in there. At the very least, the watch seems a harbinger of End Times for Walt. Tick, tick, tick.

Odds and Ends

- “Fifty-One” is brilliantly written by Sam Caitin, with the sorts of symbolically apt but not-too-obvious bits of blocking that I used to admire on Deadwood and The Sopranos. Consider the shot of Walt and Walt Jr.’s new muscle cars parked in the driveway’s only two available spots, forcing Skyler to park her station wagon on the street. Walt’s near-parodic machismo has awakened his son’s inner pig, and now they’re shutting out the woman of the house instinctively, without trying or even meaning to. Their casual piggishness is reinforced in the breakfast table scene, where Skyler tears the bacon into a traditional age number for Walt, and Walt complains that the “1” is too stubby. He has a big one now, so he demands a Big 1, and Skyler delivers it by robbing her son’s plate. The whole time this is going on, Walt and Walt Jr. barely acknowledge Skyler’s presence. She might as well be a servant. She sort of is, actually. Walt Jr.’s uncharacteristic callousness is what sparks her cockamamie plan to send the teenager to boarding school before his senior year. Whatever it takes to get him out of Walt’s clutches.

- “Fifty-One” is expertly directed, too, by Rian Johnson. He helmed one of the show’s most inventive episodes, season three’s “Fly,” as well as the high school noir film Brick and the forthcoming sci-fi movie Looper. There are too many great shots to list here, so I’ll just mention a few:

1. The shot of Walt entering the house to claim his birthday feast (plus chocolate cake with chocolate icing) from Skyler. Walt is already small when he enters the show, but grows smaller as he moves into the deep background. Walt Jr., meanwhile, is engrossed by the TV, oblivious to whatever’s happening behind him.

2. The shot of Skyler getting up from the patio table during Walt’s birthday dinner, turning her back to Walt, and very slowly moving into the pool, at once an instinctive, sincere enacting of suicidal impulses and a show staged for Hank and Marie’s benefit. Most of this scene is done in one long take as Walt spins out his nausea-inducing monologue about all the support he’s gotten since his cancer diagnosis and all the times he miraculously escaped death. (“But then someone, or something, would come through for me.”) Here, as above, a character in the foreground has no idea what’s happening in the background. The concluding shot of this sequence is a knockout, too: Skyler in the deep end of the pool, floating like a corpse until Walt finally drifts in to “rescue” her. (The kelp-haired female corpse is a workhorse shot in horror cinema: The Night of the Hunter, Carnival of Souls, and What Lies Beneath boasted similar images.)

3. The prelude to Skyler and Walt’s confrontation: a shot of Skyler in bed facing the audience while Walt looms in the background, out of focus, his head lopped out of the frame. He’s not a mate anymore, he’s a menacing body. There have been a number of similar shots this season. The bedroom scene that ended “Madrigal” was the most disturbing: the end hinted at a post-credits spousal rape.

- Speaking of Skyler: Ever since he blew up Gus Fring and his drug empire, Walt has strutted around as if he’s the Al Capone of 21st century Albuquerque, demanding fealty and blind faith. And he’s been treating Skyler as a nonperson. Once an equal partner in their marriage — the one holding things together, honestly — she’s now been reduced to providing what Chris Rock said men secretly want from women: food, sex, and silence. Skyler is responding in kind by demonizing Walt and trying to separate him from his kids, as well she should. The ominous framing of Walt externalizes what’s happening in Skyler’s head.

- Skyler’s arc thus far feels like a rebuttal to sexist complaints about her character. It’s as if the show is saying: Hey, boys, do you think Skyler is a “bitch” or “whiny,” or that she should die so that you can concentrate on the “cool parts” of Breaking Bad? Well, here you go! This is what you really want, even if you know better than to admit it. A zombie concubine. Or maybe a show with no women at all.

- This episode contains the strongest material Anna Gunn has ever been given to play, and she gives her most powerful performance to date. She’s haunting in the first half of the episode (particularly the pool scene) and briefly inspiring when she stands up to Walt. The scene reminded me of that great scene in The Sopranos episode “Second Opinion” in which Carmela goes to therapy. The therapist calls her out as an enabler and hypocrite and recommends that Tony turn himself in and read Crime and Punishment in his jail cell. He concludes, “I’m not charging you because I won’t take blood money, and you can’t, either. One thing you can never say is that you haven’t been told.” For two seasons, Hank was the show’s only consistent moral compass. Maybe now Skyler will join him.

- Walt’s cheap-as-dirt sale of his newly repaired and repainted car — the one he intentionally crashed last season while driving around doing surveillance with Hank — is so reckless and suspicious that it makes me wonder if, deep down, Walt wants to get caught. I’ve advanced this theory elsewhere on the Internet: What’s the fun in being Heisenberg if nobody ever knows you’re Heisenberg? Walt wants to be validated even if it lands him in prison or on death row.

- I love Hank’s shocked, slightly bewildered reaction to Marie telling him that Skyler cheated on Walt. He thought it was the other way around. Why? Because Walt is a man, and that’s what men do. Hank has a bad habit of assuming that first impressions are correct, a severe Achilles’ heel for a cop. He’s starting to get over this, though, as we saw in the “right under my nose” scene in “Madrigal.”

- I wasn’t sure what to make of Mike’s conclusion that Lydia was responsible for that tracking device under the barrel. He thinks it’s her convoluted way of wriggling out of her promise to give the Walt-Mike-Jess consortium meth chemicals in exchange for Mike sparing her life. I don’t buy it. Lydia is ill at ease in the warehouse. Right before Jesse comes over to replace the crooked foreman that Hank arrested, we see her fumbling with fuses (which leads to another wonderful bit of foreground action, the surveillance camera nodding off like a groggy security guard). Lydia is a desk jockey, a woman so easily flustered by the DEA’s investigation that she comes to work in mismatched shoes. She’s not capable of planting a tracking device, even one that was meant to be found. So who planted the tracker, and why? Could this be another Walter White double-reverse-mind-eff?

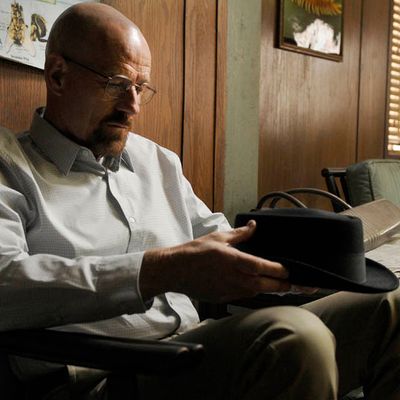

- Related: I love Walt finding his Heisenberg hat in the back of the car and putting it on. He used to only wear that hat when he was off conducting drug deals. Now he’s wearing it all the time. Dr. Jekyll is gone. Hyde is running things.

- Anton Chekov once wrote that any Ricin capsule planted in a wall outlet in the first act must be swallowed by the third. So who’s the lucky character?