Much of modern TV is said to take place in a post-Sopranos universe, but this summer David Milch’s gold-rush western Deadwood seems just as influential. The show’s cancellation in 2006 left a hole in fans’ hearts, and a glance at some of the most prominent current dramas suggests that TV’s showrunners miss it, too. Why wouldn’t they? The HBO western built a hermetically sealed world that felt like Sam Peckinpah’s Our Town. Dickensian thugs, hustlers, dreamers, and reprobates swarmed a mining camp’s muddy thoroughfares in search of sex, inebriates, profit, and vengeance, while Ian McShane’s saloon keeper Al Swearengen proffered foulmouthed color commentary. The show was dark and violent, but with a core of tenderness and optimism. It was singular and stirring. No wonder we keep prospecting in cable’s shallows, panning for Milchian gold.

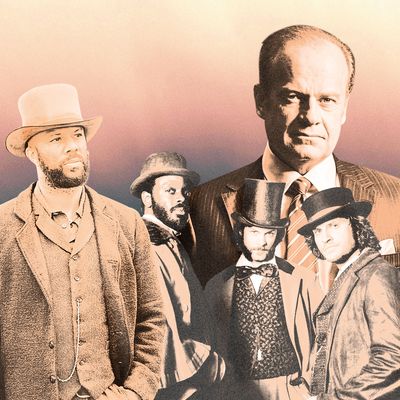

Amid the silt and pyrite, you’ll find FX’s Justified and Sons of Anarchy, 21st-century crime sagas that lean on western tropes and employ ex-Deadwood actors. HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, which returns for a third season in September, echoes Milch’s Western, too; its lavishly re-created twenties-boardwalk set feels like a cleaned-up version of Deadwood’s title encampment. Starz just unveiled a second season of Boss, a big-city potboiler that makes modern Chicago seem as lawless as a nineteenth-century urban cesspool. In it, Kelsey Grammer stars as Tom Kane, a Swearengen-esque mayor with a degenerative brain disorder who reels off anaconda-length speeches bolted together with semicolons. AMC just kicked off the sophomore season of Hell on Wheels, a show about the building of the transcontinental railroad that plays like Deadwood by way of a pot-scented counterculture western: Circa-1865 characters enact robber-baron capitalism’s bloody rise, and debate racial and sexual politics in dime-novel vernacular to a blaring modern soundtrack. Even BBC America is getting into the act with its first original series, Copper, a Civil War–era drama set in New York’s Five Points neighborhood. Equally indebted to Gangs of New York and McCabe and Mrs. Miller — both obvious influences on Milch — the show boasts muddy streets, bloody murders, and Peeping Tom camerawork that evokes Deadwood’s documentary jitters. And that’s fine. “I wouldn’t trust a man that wouldn’t try to steal a little,” quoth Swearengen. Alas, any show that steals from Deadwood is bound to look second rate.

Hell on Wheels was damned by Deadwood comparisons the instant it premiered, which wasn’t entirely fair. Westerns have had a disillusioned feel since 1969’s The Wild Bunch, and they often spotlight variations on familiar types, such as the widowed and fearful society woman who evolves into a gender-trailblazing power broker (Molly Parker’s Alma Garret in Deadwood, Dominique McElligott’s Lily Bell on Wheels) and the gun-slinging brooder with an explosive temper (Timothy Olyphant’s Mexican War veteran turned sheriff on Deadwood, Anson Mount’s vengeance-obsessed ex-Confederate on Wheels). As co-creator Joe Gayton said in an interview last year, “We’re inevitably going to be compared to Deadwood, because that was the last Western on television.”

Unfortunately, he and his brother and creative partner Tony Gayton didn’t do themselves any favors. The show feels too much like Deadwood on rails. Its ethnic and sexual power plays lack Milch’s theological and philosophical depth, and its pompous railroad baron character, Colm Meaney’s “Doc” Durant, who lectures on amalgamation and capital, isn’t fit to polish Swearengen’s boots. The first few episodes of Wheels’ second season, which pick up with Bohannon robbing Durant’s money trains and Lily making pre-feminist common cause with the camp’s prostitutes, push Deadwood away and embrace the show’s visionary strengths, drawing subtler performances (the stand-outs are Tom Noonan’s preacher and Common’s ex-slave Elam Ferguson, a bounty hunter and budding revolutionary). But there are still too many echoes, including Bohannon’s Bullock-style beatdown of smart-mouthed Yankee farm boys and the moment where Durant advises the town’s disgraced ex-sheriff turned janitor, Swede (Christopher Heyerdahl), to buck up because he “provide[s] an invaluable service to the community.” “Community … community,” Swede mutters, sounding like a Deadwood day player who misplaced his script and had to ad-lib.

Hell on Wheels is a masterwork compared to Copper, a drama about Irish cops (Kevin Ryan and Tom Weston-Jones) patrolling 1865 Manhattan. Created by screenwriter Will Rokos (Monster’s Ball) and Homicide: Life on the Street bosses Barry Levinson and Tom Fontana, it’s visually daring, constructing huge-seeming facsimiles of old New York, filling them with grimy details (horse dung in the streets, rats on windowsills), and shooting everything with handheld cameras for a you-are-there immediacy. Too bad the dialogue is weak, lead performances are so bland I can’t summon the energy to skewer them, and the cases (starting with the murder of a child prostitute in the pilot) should be horrifying but come off as merely tawdry. Aside from the production design and Ato Essandoh’s performance as Matthew Freeman, an African-American who studied medicine in the war and performs autopsies in secret, this show is dead wood.

I’m adopting a wait-and-see attitude about Boss, the Starz drama from Apocalypto screenwriter Farhad Safinia. Early in season one, it felt like an adult-comix version of The Wire, overlaid with Deadwood-style theatricality. Its earnest declaiming on the Grand Traditions of Big City Life didn’t match its Michael Douglas–movie mix of rough sex and sadistic violence, and when it killed off its most fascinating character (I won’t say which one in case you’re not caught up), it made me so mad that I didn’t watch the finale for months. The first four chapters of season two go in a figurative, hallucinatory direction. The mayor’s disease advances, and he suffers prolonged, intense visions, some of which are woven into otherwise “realistic” scenes: There are recurring shots of a desert landscape and a tiny lizard, and dead characters loiter behind living ones, glaring in judgment. Grammer is still spooky-good, especially when Kane is at his most battered and fearful — shades of post-kidney-stones Al Swearengen, with his bloodshot eyeballs and nervous muttering — and the byzantine politicking has a Milchean sense of the absurd. I suspect Boss might have been better off as a ten-episode miniseries. But Safinia disagrees, of course. “We have to do justice to the central character we’ve created,” he told The Hollywood Reporter. “Tonally, I think we’ve hit the right notes and I’d like to keep going in that way.” To which Swearengen would reply, “Announcin’ your plans is a good way to hear God laugh.”

Boss, Starz, Fridays at 9 p.m.

Copper, BBC America, Sundays at 10 p.m.

Hell on Wheels, AMC, Sundays at 9 p.m.

This story appeared in the August 20, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.

Related Stories: Seitz: Hell on Wheels’ Second Season Continues to Show Promise When It’s Not Killing Time