For 30 years, my reaction to the complexly speculative art of Richard Artschwager has been ÔÇ£Huh?ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs like his work speaks in some alien language that only occasionally gets through to me. I can love any one of his ┬¡quasi-photo-realist monochromatic paintings on CelotexÔÇöoddball things on crenellated surfaces, with blurs of charcoal that coalesce into images that then disperse into abstract patterns. Yet seeing lots of them turns the effect redundant and I glaze over. Similarly, I can marvel at the magnificent oddity of any one of his oversize geometric Formica-covered ┬¡furniture-sculptures that look like crates but are art that acts like furniture. In groups, theyÔÇÖre boring.

But my Artschwager ice has cracked. Perhaps thatÔÇÖs because almost every young artist I know adores his work. Maybe my eye has finally acclimated to the oddness. In this impressive Whitney retrospective, ArtschwagerÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Huh?ÔÇØ feels vinegary and insistent, and I am reminded of what Ed Ruscha once said: ÔÇ£Good art should elicit a response of ÔÇÿHuh? Wow!ÔÇÖ as opposed to ÔÇÿWow! Huh?ÔÇÖÔÇàÔÇØ ThatÔÇÖs Artschwager.

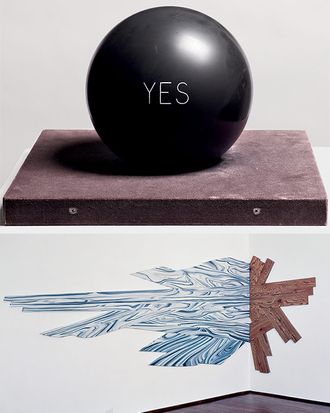

To see what Ruscha means, consider two typical Artschwager sculptures. ┬¡Journal II is a sprawling splat on the wall, hung in the corner. Made of plywood and Formica, it looks like a burst of marbleized black-and-white painted woodgrain pattern exploding out of what looks like floorboards. (Art┬¡schwager once called Formica ÔÇ£the great ugly material, the horror of the age,ÔÇØ and has used it often.) The faux wood appears exaggerated, enlarged, unreal, visually out of focus, pictorial like a painting but solid like sculpture. Menacing, too, like itÔÇÖs coming into your spaceÔÇöbut cartoonish, like it exists in another perceptual dimension where flatness has density. Its orientation flip-flops in your mind, from flat and frontal to 3-D isometric.

Nearby, Description of a Table is a classic minimalist cube, also made of melamine laminate, inlaid to look like a white tablecloth draping a piece of brown wooden furniture with dark space underneath. Yet the thing never stops being a solid. Or seeming extremely odd. Or creating rippling mental echoes. This is ArtschwagerÔÇÖs primal ÔÇ£Huh?ÔÇØ You think, What are these things? Sculpture? Furniture? Architectural ornament? Illusions? Jokes? Categories cross and collapse. Slowly the works transform from ÔÇ£Huh?ÔÇØ into ÔÇ£Wow!ÔÇØ You also begin to understand that bad art does the opposite, ending up at ÔÇ£Who cares?ÔÇØ

ArtschwagerÔÇÖs sixties grisaille paintings of buildings, porno scenes, train wrecks, and rocket ships, made by gridding out photos, look spectacular here, and super-prescient. Like Warhol, Richter, and others, Artschwager explores the charged spaces between painting, photography, illustration, mechanical reproduction, popular culture, and banality. Unlike them, however, Artschwager paints on kooky Celotex, an industrial material whose texture is irregular, with swirls of slightly raised fibers. This means that your eye is continually returning to the surface patterns of the painting. ItÔÇÖs like looking at a Seurat drawing or a painting by Vuillard. The weaves and irregularities become as important as whatÔÇÖs depicted. Wild! I surmise this is why Artschwager uses such bulky, ugly frames. He wants you to see them as part of the whole artistic ball of wax, not just as decorative fluff. Another wow.

The most unsatisfying part of ArtschwagerÔÇÖs art, for me, is its near absence of color. When his sculptures do incorporate color, itÔÇÖs always only when a material is left as he found it. Blue Formica stays blue; raw plywood remains raw. But he somehow makes Formica look radical. As in the GuggenheimÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Picasso Black and White,ÔÇØ or the WhitneyÔÇÖs own Wade Guyton survey, itÔÇÖs as if adding one more formal element would just be too much for Artschwager to manage.

Why this should be might be explained by Yes/No Ball: a plain black bowling ball with the word yes on one side and no on the other. A conceptual gimmick? Sure. Yet contrast the ball to a coin-flip, which always gives you one side or the other, black or white. Here is Art┬¡schwagerÔÇÖs permanent aesthetic condition: The coexistence of yes and no, almost, in ┬¡between, not quite, both, and neither. Artschwager says, ÔÇ£If you have a lot of these balls, then you have a model for inductive reasoning, which is the only kind of reasoning weÔÇÖve got.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs that beautiful, bountiful ÔÇ£Huh? Wow!ÔÇØ

Richard Artschwager! Whitney Museum of American Art. Through February 3.

* This article originally appeared in the November 19, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.