Over the next few weeks, Vulture is talking to the screenwriters behind 2012’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. What pivotal sequences underwent the biggest transformations on their way from script to screen? Today, Chris Terrio discusses a tonally tricky scene from Argo:

One of the more common critiques of a screenplay one is likely to hear in Hollywood is that a script has “too many men in rooms talking” (which always strikes me as bizarre, since roughly two thirds of The Godfather consists of men in rooms talking. Taken to heart, this note would have given us the tarantella and not “I believe in America” as the opening of the greatest Hollywood film ever made). I knew before I even attempted to write what became Scene 58 of Argo — a scene of nine men sitting in a conference room talking through various scenarios for a cover story to get Americans out of Iran — that the scene would be more difficult to pull off than any of the more (ostensibly) complicated set pieces in the film.

A scene at Mehrabad Airport in 1979 is, by comparison, easy to write, because the story can be told through images: a portrait of the Ayatollah glowering over a crowd; the glimpsed tragedy of a refugee woman being yanked away from her husband. It’s the juxtaposition of image against image, as any good Bolshevik filmmaker knows, that tells the story; yet in a conference room, there’s nothing to cut to except the actors’ faces. The writing in a scene like this is, in effect, naked. The tension has to come from the audience’s awareness of subtle shifts of power in the room.

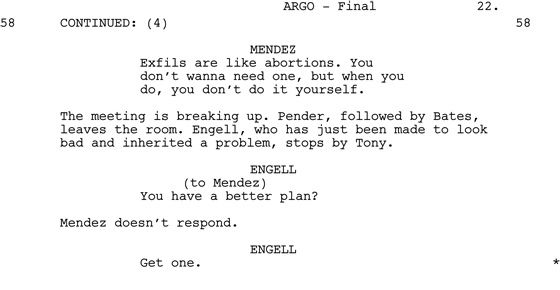

As Scene 58 proceeds, top-floor officials from the CIA and State Department debate ideas for cover stories, each idea worse than the last, though no one in the room dares to point out that these Important Men thinking Important Thoughts are, in fact, delusional — no one except our hero, Tony Mendez. I knew that the crucial beat in the scene (and a major turning point in the film, both for its story and in its tone) would come when Mendez finally decided to speak up to his superiors, exposing the absurdity of their plans and, in effect, volunteering to take over the Tehran operation. I also knew that the moment was fraught: Mendez is a jaded CIA veteran, not an innocent pointing out that the bureaucratic emperors are naked. He couldn’t seem smug, or overtly disrespectful to his superiors, and he needed to speak in the jargon of intelligence professionals. Yet he had to make his case and lay bare the absurdity of the State Department’s plans (which, incredibly, were real: Officials at Foggy Bottom wanted to put the six escaped Americans on bicycles and tell them, in effect, “Pedal north until you smell Turkish food”).

As I wrote and rewrote the scene, trying to get the tone right, I found myself returning to screenplays by writers like Chayefsky and Goldman, two masters who were writing at the time that Argo takes place (Goldman is, of course, still writing and still a master). In their films of the period, one line spoken by a man (or a woman) in a room could change the tone not only of a scene, but of an entire film. And these writers could do it without grandiloquence, but with precision, and often with spitballs — shifting a conversation with an ironic barb that could render the boardroom of a television network or an editorial meeting at the Washington Post speechless. How would these guys write the scene?

I settled on the idea that Mendez would throw a spitball into the self-serious conversation by making a joke about giving the bicycle escapees Gatorade. (Which meant I had to determine whether Gatorade was on the market and a commonly recognized brand in December of 1979. I celebrated when I found a Time Magazine from the year before featuring a dehydrated athlete with a Village People–style mustache: “Gatorade: When You’re Thirsty to Win.” So the Gatorade could stay.) Mendez would make his off-hand joke. The table would go silent. The attention of the room would shift to the court jester speaking truth to power.