Over the next few weeks, Vulture is talking to the screenwriters behind 2012’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. What pivotal sequences underwent the biggest transformations on their way from script to screen? Today, William Nicholson discusses a sequence from Les Misérables, which needed a brand-new scene:

This is not a usual screenwriting assignment. I was hired to turn the super-successful stage musical into a movie — a show I admired and loved. From the start, my brief to myself was: Don’t screw it up, don’t fix what isn’t broken. However, the process of putting the story on screen demanded some changes. Throughout I was to proceed under the eye of the original creators of the show, who rightly retained authorship in the movie.

My first drafts tackled these issues by inserting new dialogue scenes, or by taking sequences of recitative and giving the lines more work to do. At the same time I worked out how to turn a show that presents everything in a single space into a movie that moves through locations. I kept all the main songs except “Dog Eats Dog” and “Castle on a Cloud” (which was later partly reinstated). My work proceeded via various drafts, which were then the subject of meetings with the show’s creators.

When Tom Hooper came on board as director, about eighteen months after we’d started work, he made a crucial, brave, and brilliant decision: to have the movie be sung throughout, just like the show. This meant my dialogue inserts had to be reconfigured as recitative, and scored along with the rest of the music; and this job could only be done by the original team of composer-writer-lyricist, Claude-Michel Schonberg, Alain Boublil, and Herbert Kretzmer. Because this was a slow process, Tom asked me to rewrite the new dialogue as lyrics myself, so that he could assess the effectiveness of the screenplay as he evolved his shooting plans. I did this. My new material was then worked on by the show’s authors, who recast it in their own way, so that the lyrics and music kept a unity of style and voice with the material taken unchanged from the show. My job was therefore essentially structural — to build a new structure, assign new material to its place, and stand back while it was integrated into the score.

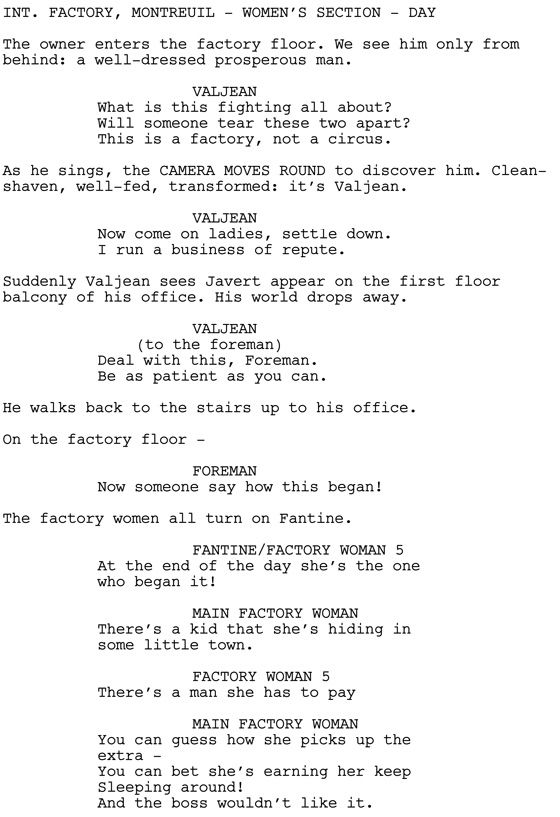

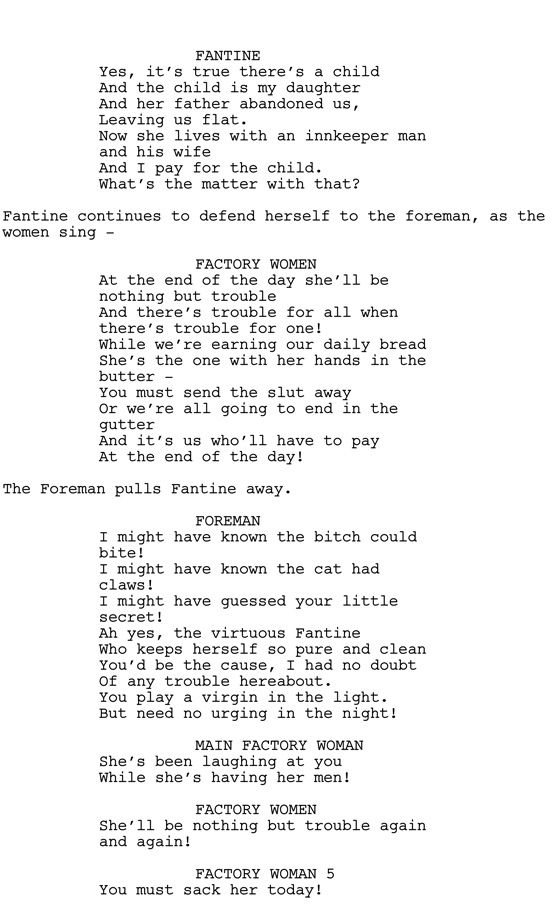

This can best be explained by a specific example. In the show, after Valjean tears up his ticket of leave, the action moves straight to the factory in Montreuil, with the anthem “At the End of the Day” creating the junction. Several problems arise. We never learn how Valjean has become rich. When Fantine is dismissed by the lecherous foreman, Valjean seems to have very little responsibility for her plight, which is damaging, because his guilt over Fantine motors all his subsequent actions. And later, in the red light district scene, Javert shows up in Montreuil in a manner that is unexplained and over-coincidental.

To solve all these problems we did the following:

1. The junction song “At the End of the Day” became Javert’s journey across France, which allowed us to show the plight of the poor of the nation, and to indicate that Javert is moving to a new posting.

2. Javert’s arrival in Montreuil coincides with Fantine’s scuffle in the factory. This means, crucially, that Valjean’s initial intention to involve himself in the dispute on the factory floor is overtaken by his sudden chilling realisation that Javert has followed him. He abandons Fantine in fear for himself. This is a proper basis for his subsequent guilt.

3. We then created a new scene in which Javert introduces himself to Valjean in his capacity as the new chief of police. This scene gave room to establish that Javert half-recognises Valjean, and allows us to sneak in a little information on Valjean’s business. It also enhances the tension, of course: We’re now waiting for Javert to expose Valjean …