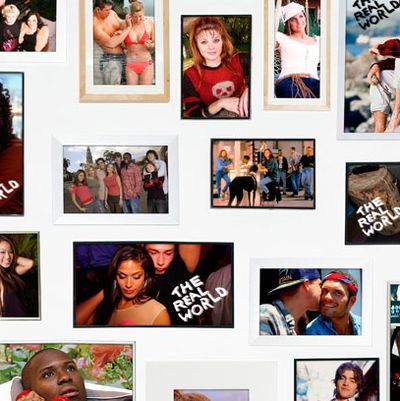

Later this year, MTV will debut the 28th season of The Real World, set in Portland, Oregon, and in May, the show will celebrate its 21st birthday (although it has been drinking for years). I am 33, an age at which most once-loyal viewers have moved on from the series. Usually I either hear from my peers the complaint that it’s a shadow of what it once was or that it’s a dumb show, has always been dumb, and our younger selves just didn’t have the sense to know it. But I don’t have this feeling of disgruntlement at all — to me, this pervasive belief that the show has lost itself seems a result of the distorting effect of nostalgia. I will be eagerly tuning in again so as to continue my near-perfect record of watching since season one. Up until beginning this essay, I thought I had seen all 27 seasons, but upon scanning the show’s history, I realized I missed one: season 22, Cancun. Extremely curious about what had been going on in my life that kept me from watching, I looked up Cancun’s premiere date. It kicked off on June 24, 2009, right when my dad was in the middle of radical treatment for terminal brain cancer. And while that’s a bummer note to start on, leading with the announcement of a personal trauma is in the grand tradition of Real World introductions.

I’ve long since aged out of the show’s demographic: A casting call from last year says, interestingly, that you can audition if you’re at least 21 but “appear to be between the ages of 20 and 24.” (If you’re a supremely youthful 40, go for it?) I tried out once, while going to school in Providence in 1997. The casting was held at a multilevel darkened nightclub, where the producers broke us into small groups, then asked what qualities we had that might make other people jealous or annoyed with us. Being an introvert, I withdrew into my head as soon as the more aggressive types began shouting over each other while forcing intense eye contact with the producer. I probably should have sent in a video instead.

I was 11 years old when I saw the first season of The Real World. Initially I was drawn to the show because it was what I imagined the adult version of my life should be. Life was when you busted out of your parents’ stupid house and you went to a major city, got a cool house (although maybe not one so frenetically decorated) with a bunch of characters, and regularly stayed up until 4 a.m. It was the fantasy of an intimate, co-ed fraternity. In the early seasons, I innately assumed that most of the cast members were much older. Dominic and Beth of season two (Los Angeles), both 24, read to me more like 35 — that’s how far away they seemed. Responsible Deputy Marshal Irene was actually the oldest housemate at 25, but I think her gigantic bush of bangs infantilized her.

In the early years, I tended to identify with the female cast member of each season whom I thought displayed the kind of moxie and toughness I would have when I finally broke out of Orange County and made my way into the world. There was Kat in season four’s London, who was so smart and great at fencing (fencing!) that she charmed dreamy techno-noise aficionado Neil, even though he hated everything. I took to Montana of Boston (season six), atheist and feminist, who was also very smart even if she did possibly let some kids sample alcohol at the after-school volunteer program. (This wasn’t as big of a deal to this reform-Jewish viewer because I’ve been offered Manischewitz since I could read.) You can tell what a child I was during the series’ early, halcyon days by the fact that I looked up to Kaia from Hawaii (season eight). As her van pulled up to the house, she explained in an interview, “It’s not just that I have so much charisma that I walk in a room and people look at me. It’s that I back it up.” I was a person who couldn’t walk into a room without wanting to walk back out of it, so I was sold. By the end of the first day, she was walking around the airy manse topless (I always wanted small boobs) and speaking to everyone in a Guinness World Record–level vocal fry. Had I seen this season later in life, watching her announcement that she’d changed her name from Margaret to Kaia because it was Swahili for “stability” would have caused my eyes to roll so far back in my head that they would fuse into an extra vertebrae. And rewatching her scenes as an adult revealed that her biceps and shoulders stiffened when she was topless, because she was only performing the role of someone comfortable with herself. But at age 19? I thought that she was really cool, and I had no doubt it was her charisma and nothing else that got a stranger to give her that excellent Janet Jackson concert ticket.

Still, even after I got too old to admire young people who were already weary with the world and casual nudity, I never missed an episode (except for Cancun, my white whale!). I still loved — and love — seeing the cast members’ quirks unveil themselves as they settled in with the group. This is the truth that scripted television usually forgets or can’t allow itself, that people can have major contradictions in their personalities and still be legible characters. I also love to watch the personal gravitations, to discover who was drawn to whom and for what deep-seated reasons. That aspect of the show hasn’t changed. But old-school viewers remain adamant that The Real World has deteriorated, as if the original enterprise were some pristine experiment that got sullied as the conditions in the lab got sloppier.

The biggest accusation seems to be that the housemates used to have more substance and now they’re just cast for looks. But gazing backward, you have to take into account that everyone looked much worse in the early nineties. Julie from New York was no less cute than Trishelle from Vegas; it’s really just a matter of styling. Marie and Laura from last season in St. Thomas are cute girls who are certainly on a par with season one’s Becky (New York) or season three’s Rachel (San Francisco). I don’t think Eric Nies was cast for his unique perspective on steroid use.

The way I see it, the show has always had a dominance of mostly extremely attractive cast members and then a couple who fall outside society’s stricter beauty norms. In San Diego (season 26), for instance, you had Zach, who could stand in for Thor, and Alexandra, who looked like the digital stunt Time would run as the ideal multicultural beauty of the future. But you also had Nate, giving insight into what Alfred E. Neuman would look like with Hilary Duff’s veneers, and androgynous Sam, who was certainly no Shane from The L World. I could go through each season and separate the super-objectively hot from the housemates who are somebody’s type, but it seems cruel to do a comprehensive rundown of all the people you’d probably only go home with because you wanted to see the Real World pad up close.

The criticism that the show lacks a substance it once had is a more complicated issue. There has been somewhat of a shift away from honing in on issues and toward more layered personal interactions: Whereas you had African-American Kevin coming in to season one as the guy who almost single-mindedly wanted to discuss racism, by the time we got to the “Back to New York” tenth season, the flirtation between Malik and Nicole, both biracial, deteriorated over Malik’s right to wear a Marcus Garvey shirt and also date white women. Their frustrated romance was the main focus on these cast members — underneath it all, Nicole wanted Malik to only have eyes for her — but the two didn’t seek each other out for the purpose of having a racial debate. In season three, Pedro joined the San Francisco house to educate his roommates and viewers about gay men with AIDS, but by season eight (Hawaii), Teck was asking Justin if he was gay the second he walked up to the pool. Justin seemed more taken aback by the hasty reveal than anyone else in the cast, so a naked, swimming Ruthie announced to Justin she was bisexual with a military girlfriend back home, in order to make him feel more comfortable. It had become a known thing that MTV was probably going to put a gay person in the mix, and so once the roommates started to understand who was filling what role, they began to quickly move on to more intimate grievances with each other. By the time you got to San Diego’s second go-round (season 26), you had Frank’s narrative becoming much less about him being gay (even while living with a roommate who was nervous about encountering gay sex) than about him being one of the more emotionally exhausting, solipsistic people ever to land on the show — and that’s saying a lot. The show is still in conversation with important, relevant social issues; it’s just that since the first couple of seasons, The Real World has tonally relocated from the seminar room to the kegger. Looking back on the early days, there is sometimes an artificiality to the endeavor, with cast members coming into the house with an agenda and never veering from it (this is the same problem I have with almost every network drama). As the show has developed, though, the housemates have become people instead of just podiums, and you can’t dismiss these explorations of issues as hollow just because they’re framed less academically. You have to consider the ways in which the sloppiness is even more realistically productive.

But ultimately, criticism that The Real World has devolved into a lesser enterprise comes from the viewers who came of age alongside it, not the teens of the moment that MTV has always existed for. Olds like me feel the most proprietary toward the show because we were there from the beginning, even if we’ve mostly matured out of the phases of our lives when bonding and puking alongside six strange roommates seemed fantastical. I had once dreamed that the adult version of my life would include this kind of destination partying, but once I reached the age where I could live on my own, I didn’t even really like going out. I didn’t want to have roommates. As evidenced during my failed audition, I’m a thorough introvert who would completely hate living in a Real World house. I would have taken my Ikea comforter to the confessional room and never come out.

And yet I continue to watch, season after season, and enjoy the series because it still captures something about the magic of an experience I want to want to have. It’s a vast slumber party where you could meet your new best friend or your next big love. It’s the vicarious thrill of what a new place and new people could mean to your life. This past summer, I had my first baby, and in the midst of great existential dread and disorientation, I religiously watched as Marie and Robb fell in tumultuous infatuation in St. Thomas, she the extroverted, swaggering daughter of an SVU cop mom (I pictured a blonde Mariska Hargitay) and he the tortured, ginger basketball player who self-mutilated when disappointed in himself. Just two people in this great, wide world who happened to have the exact same “hakuna matata” tattoo. My boyfriend would uncontrollably laugh at what my face would do when the two of them came onto the screen. He said he’d never seen me look happier.

The next city up is Portland, and I’m not at all daunted by Wikipedia’s reporting that two of the cast members have Model Mayhem profiles, while another is a Hooters waitress. It will be business as usual: These people are mostly going to be hot; they will be overconfident; they will be vulnerable; they will pine for someone; they will screw someone over; they will misunderstand each other; they will fight; they will be filled with nostalgia on the last day of taping. And I cannot wait to learn their stories. I will put my infant daughter to bed, sit down in front of the television, and say to the new housemates with open arms, “Come on, be my baby tonight.”