The Paley Center for Media, which has locations in both New York and LA, dedicates itself to the preservation of television and radio history. Inside their vast archives of more than 120,000 television shows, commercials, and radio programs, there are thousands of important and funny programs waiting to be rediscovered by comedy nerds like you and me. Each week, this column will highlight a new gem waiting for you at the Paley Library to quietly laugh at. (Seriously, it’s a library, so keep it down.)

Albert Brooks, stand-up, author, actor, and comedy legend, was interviewed in the January 2012 issue of Vanity Fair which was guest edited by Judd Apatow. In it, Judd, a comedy vanguard himself, describes Brooks as “the prototype. He’s the original smart, sensitive Jewish neurotic guy, with huge flaws and a heart of gold.” But what’s most fascinating to me is that this statement was true about the man from the very beginning of his comedy career, which began while he was in his early twenties. In the late 1960s and early 1970s when he began playing on the national stage, his comedic character already seemed fully formed, and he never lost sight of it or compromised his unique voice as he moved from stand-up to television to film.

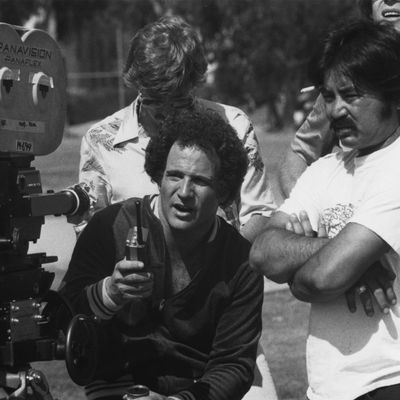

Today we look at seven early short films from Albert Brooks, which he produced for television in the early seventies, which the Paley Center helpfully compiled together, without the laugh track that at least one of these shorts would later be broadcast with. I was immediately struck by how packed with jokes these short pieces are, and how Albert manages to create a cohesive tone for his work, despite being only 26 when he made the bulk of these.

Albert Brooks’ Famous School for Comedians (1972)

This short film originally aired as part of a satirical PBS show called The Great American Dream Machine, which in addition to Albert Brooks’ contributions also featured pieces from Andy Rooney and included Chevy Chase in its cast. The film is a parody of The Famous Artists School, which advertised in many publications from this time. But the short’s history actually goes back a little further as it was born of an article written by Brooks in Esquire in the February 1971. (The article can be read here on Splitsider in a great piece written by Dave Nuttycombe.)

The clip begins with Brooks introducing his school that takes up “twenty-two gorgeous acres by Arlington National Park” and giving us a tour of the campus. He strolls down a mall, where students often walk down and try out material on one another. One student does so with Albert, who compliments the student on the use of his hand gestures while he tells the joke. We see a group of students hanging out at the Jack Klugman Comedy Research Center and Cafeteria, a subtle dig at the actor who up until that point had mostly been a dramatic actor before turning to comedy on the TV show The Odd Couple.

Brooks gives us a tour of some of the classes. The first, which you can see in the clip below, is a class on comedy takes, and we see a group of students working on the spit take.

Unfortunately this particular clip comes not from the original airing but, according to the comments, a later special hosted by Milton Berle with comedians talking about comedy. In this broadcast a laugh track was added, which makes it impossible to hear the instructor’s critique of his class’ performance: “That’s much better, except again, Carol, you didn’t put the liquid in your mouth and you gargled for the fifth straight time!”

Other classes include a comedy technique class in which an instructor shows us the three most desirable areas in which one might hit a person with a pie: Area 1 being the center of the face, Area 2, the side, and Area 3, the neck. He demonstrates these with a stoic man standing up front, analyzing the humor of each area. The third class we visit is one that helps comedians determine what serious cause they will use their talents to benefit in case they make it big. When we step in there is still “eczema” left, and several different types of cancer.

This particular short is packed wall-to-wall with jokes, including a sign that is on the screen for a split second as Albert walks by that reads “Lecture Today: Funny or Bad Taste? Today at 3 in Deluise Hall.” Back in his office, Albert tells viewers how they can get a copy of the Famous Comedians School Test which, when you read, you will see is also packed with jokes, before saying goodbye and taking an important-sounding call from Las Vegas.

The remaining six short films all appeared in the first few episodes of a show that premiered in 1975 that went by the name of Saturday Night Live. These don’t appear to be anywhere online, but can be found on the SNL Season One DVDs. In Tom Shales’ oral history of the show, Live From New York, Albert talks about how Famous School for Comedians actually got the attention of NBC executives who offered him the 11:30 Saturday time-slot before SNL existed. Brooks was more interested in continuing to make films and claims that he suggested to NBC that instead of him hosting every week, that they should have a rotating guest host. They liked the idea (clearly) but still wanted him involved, and so he ended up contributing these six shorts to the program.

The Impossible Truth (October 11, 1975)

This short, which appeared in the very first episode of SNL, is actually the one that features Brooks the least. This piece is set up like an old-timey newsreel made by The Weekly World News and features a variety of short blackout jokes, with Brooks as the off-camera reporter asking questions to such subjects as a temporarily blinded New York cabbie who is still driving, or an adult man on a date with a elementary-aged girl after the age of consent was lowered to the age of seven in Oregon (“Although The Impossible Truth airs what it must, some things it airs disgusts it”). One segment features a press conference in which the state of Georgia and the country of Israel announce that they are going to switch places, geographically. The Israeli leader quips: “I hope that New Orleans will be easier to deal with than Cairo,” and the representative from Georgia says in his drawl, “I know that my entire state is looking forward to heat without humidity!” The sketch is short, sweet, and moves very quickly.

Home Movies (October 18, 1975)

This piece, which I actually believe was intended by Brooks to have been aired first, serves as an introduction from Albert to himself and his unique brand of humor. For those who aren’t familiar with his work, he offers some footage from some folks who just saw a current movie. “Psychedelic and entertaining!” says one filmgoer, presumably not about anything related to Brooks. Albert chooses to introduce himself by showing some home movies his parents made. Unfortunately he is interrupted by his daughter, who becomes annoying and is then escorted out by the police officer that happens to be standing behind him. “Sorry about that,” he tells us. “You won’t be seeing her again.” Each of the home movies he shows feature his father being invasive or cruel, either pushing the small baby Albert down, or trying to film him going to the bathroom for the first time (at six) or his first kiss (at eight) or the first time he made love to a woman (at fifteen). He then shows us some clips of what he won’t be doing on the show, which include him trying to buy an airline ticket while dressed as a cow. Unfortunately, the woman at the counter immediately recognizes his voice and is completely starstruck. This piece is closer in tone to Famous School for Comedians with Albert being front-and-center and ending with parody, in this case, skewering Candid Camera’s pranks.

Heart Surgery (October 25, 1975)

While most of the shorts made for Saturday Night Live came in at four or five minutes, this one ran thirteen minutes, and according to Brooks again in Shales’ book, initially Lorne refused to air it. However, when Rob Reiner, a friend of Albert’s, hosted, he insisted on showing it. Lorne states that his hesitance was that due to its length it “necessitated commercials in the middle and on either end — which meant we were away from the live show for close to twenty minutes.”

The piece follows Albert as he follows his dreams and for one day and becomes a heart surgeon by placing an ad in a paper expressing a desire to perform a heart bypass. He finds an interested party, hires a team of doctors, argues constantly with them, locates an anesthesiologist (having forgotten to do this prior to the surgery), until suddenly an unexpected, unavoidable tragedy strikes: the anesthesiologist dies from a heart attack. The rest of the crew plays a prank on Albert, which breaks the tension (“You stupid jerk!” says one of them to Brooks, who thinks he’s in on the joke). Brooks brings in the patient’s wife to take a look at their progress, and even as the anesthetic wears off and the patient begins to sing “buy some peanuts and Cracker Jack!” on an endless loop, he pulls through. This piece is also stuffed to the gills with jokes (and real science facts!), but I can only imagine how it may have suffered with a commercial break placed in the middle.

Mid-Season Replacement Shows (November 8, 1975)

“Even a super season has super failures! That’s why at NBC, we’ve got super replacements!” So begins the announcer at the start of this short in which we see three mini-sketches, each of them presenting a skewed version of the popular genres of television, and each of them an endless parade of one-liners. The first, a medical drama called “Medical Season,” feels a bit like a prototype for Childrens Hospital, as inept doctors make their way through the workday. A nurse tells someone on the phone that she’s a “registered nurse… not a registered prostitute.” Two doctors (one of whom is a young Rene Auberjonois from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) argue about the ethics of keeping a patient alive and the fleetingness of life: “You could be hit by a car driving home today!” says one. “I’m not going home today!” the other angrily retorts. The next show, a sitcom parody, is called “The Three of Us” and features Brooks as “Bob,” who lives with his wife Cathy and her best friend Susan, and the plot of this imaginary show seems to focus solely on Bob’s attempts to get these two women to agree to a ménage à trois. He is consistently, wildly unsuccessful. The last show, “Black Vet,” is about Dr. Bowman, “a young black veteran from the Vietnam War who returns and takes up practice as a veterinarian in a small Southern town.” The clips from this one are very short and punchy, and in my opinion, the best of the three. Dr. Bowman is told by a man that his dog Duke doesn’t want to operated on by a black doctor (it’s the dog’s decision). We see our hero holding the collar of a young man as he slowly and seriously tells him, “I’m not the kind of vet that believes in drowning cats… except the kind that go after my wife.”

This short film was mentioned in a review of Saturday Night Live by Newsweek as being particularly clever, but much to Brooks’s chagrin, they attributed the work to the cast and writers in New York rather than to him. In Shales’ book he states that Brooks is “still irked to this day” by this fact.

Sick in Bed (December 13, 1975)

In the most stripped-down of any of the SNL shorts, Brooks explains that he’s sick and stuck in bed. To prove it, he calls his doctor on speaker phone (voiced by future SNL cast member and Simpsons star, Harry Shearer) who tells the audience that Brooks is overworked and it’s a miracle he’s still alive. A delivery boy enters with Brooks’ food who, when told a movie is being made, asks where the girl is. The delivery boy suddenly recognizes Brooks as the creator of the new record A Star is Bought and the short slowly turns into an advertisement for the release (despite the fact that its name and label are bleeped every time they’re mentioned). Some sample questions from the delivery boy posed to Brooks include “Why don’t more people know about [your record]?”, “Why doesn’t the record company take out ads?”, and “Are they spending too much money promoting The Eagles?” It’s a funny bit, but I can’t imagine that his attempt at free advertising went over to well with the folks at NBC in New York.

Brooks ends the video with one last thing, which I found funny enough that I wanted to include it in full here: “Making film is a cooperative effort. It takes a lot of people who are willing to put out good work. There’s been one gentleman who works at a very large film processing house here in Los Angeles. I asked him to watch tonight. He’s never put out good work. I’m not gonna mention his name. Oh, yes, I will. Jack Stanton is his name. Now, from the very beginning of these films, he’s the man who says, ‘They’ll never see it. They’ll never see it.’ …Well, you know something? Maybe you’re right, Jack. … But if they’ll never see it, I’m sure they’ll never see this either, Jack.” At this point he holds up a sign that reads “You are the ugliest man that ever lived you stupid jerk.”

The National Audience Research Institute (January 10, 1976)

In this short, Brooks takes us to The National Audience Research Institute outside Phoenix, where three men and one woman work with him to figure out what people don’t like about him and how he can change that. (I couldn’t identify one of the men, but the doctors were played by Julie Payne, Albert’s brother Cliff Einstein, and comedy impresario James L. Brooks.) We see a variety of tests done by the institute that include setting up a live video feed in which TV viewers talk with Brooks, but they’re only interested in talking about how the technology works, hooking a viewer up to a complicated computer as they watch Brooks’s Sick in Bed short, and having a man who hates Albert’s comedy argue with him in person while the exchange is observed by the team. Brooks is given an 800-plus page report, which he promises to have a friend he trusts put into a synopsis for him.

As Saturday Night Live evolved into the show it is today it moved away from the variety show format and shed the short films, the multiple musical guests, and the Muppets. In the Tom Shales book, Brooks suggests that the reason his shorts didn’t continue was because he was out in Los Angeles, working independently, outside of the studio. Whatever the reason, although this was the last of Albert Brooks that we’d see on Saturday Night Live, the experience with these seven short films had paved the way towards his esteemed film career, beginning three years later with the film Real Life. Speaking of which…

Bonus! Real Life Trailer (1979)

While not technically a short film, the trailer for his first film works completely on it’s own and shares the tone of the shorts discussed above. Oh. And it’s hilarious.

Ramsey Ess is a freelance writer for television, the head writer of his website, a podcaster and a guy on Twitter.