Editor’s note: This piece was originally published three years ago, prior to the release of David Bowie’s 2013 album, The Next Day.

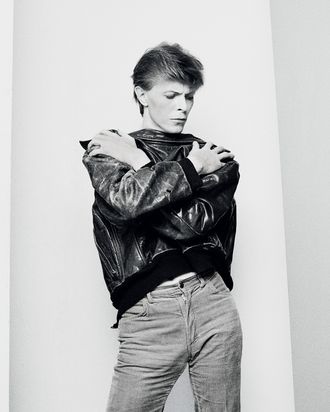

I very rarely have felt like a rock artist,” David Bowie used to say. “I’ve got nothing to do with music.” More than 40 years on, we see now he was dissembling on both counts. But as with any great act of self-creation, there was an element of truth in the obfuscation, and the roles he was playing in addition—some species of musical-theater provocateur, a high-art celebrity indulging in a low-art mechanism, a transgressive social poet manipulating a pop-cultural moment—seem plain. He was the first rocker to deliberately separate himself from the personae of his songs and onstage characters in a way that challenged his audience. The stardom that resulted was unlikely—he was, let us remember, a self-described gay mime. But he did it at a time when rock had grown a little too serious and self-satisfied, and life in his homeland was in many ways bleak. “Your imagination can dry up in England,” Bowie reflected. He wanted to show us that music still had the capacity to wow and outrage, to open new worlds. And since he was also one of the most adventuresome songwriters of the day, and because in those songs there was frequently something human and real, he pulled it off. David Bowie—indigestibly arch; unfailingly cerebral, distant, and detached—was always sincere about his insincerity, but never insincere about his sincerity. At the time, this distinction was as crucial and confounding as the highly sexualized, polymorphously perverse demimonde he celebrated. He mocked rock seriousness, even as he delivered some of the most lasting songs of the era, all the while carrying himself like a lubricious aristocrat, drawing, with a sort of kinky noblesse oblige, strength from his audience’s adulation and in turn bestowing his blessing: E pluribus pervum.

We blink, and he is nearing 70, courtly and calm. The onetime un-not-watchable figure has been uncharacteristically quiet for nearly ten years, perhaps because of a collapse backstage during a tour in 2004; it turned out he’d had a heart attack. But now he is returning with his first release since 2003’s Reality, titled The Next Day. The reviews will routinely note that producer Tony Visconti—a key collaborator somewhat cruelly discarded in Bowie’s salad days—is back. But Visconti has come back to help him before, and the results were the quickly forgotten Heathen and Reality, so let’s not get our hopes up. The new record hasn’t been heard yet; security is tight, and it’s not even on the file-sharing networks. The cover is extremely, almost unprecedentedly odd—a replica of Bowie’s iconic “Heroes” cover but with a large white void in the middle.

The first single, “Where Are We Now?”—which Visconti and guitarist Earl Slick say is not representative of the album—is a mournful electronic work, in which Bowie, somewhat sadly, name-checks geographical memories from his Berlin era. From a man who never looked backward, it’s hard not to take the song as a bit of an envoi: “Where are we now?” he asks, again and again.

More interesting is the video, by New York multimedia artist Tony Oursler, that accompanied the new song’s release. It contains evocative shots of Berlin; Bowie himself appears mostly in a small window through which we can see his face but not his hair. It’s not flattering, but it is a naked and revealing moment for a man who’d almost always appeared in a guise of one sort or another. Where are we now, yes—but also, where have we been?

Bowie started out as a scenester, a hustler. He was questing for stardom from the age of 16 in 1963. He would do anything—appear in commercials and low-budget movies, drawl as a folkie, hop as a bluesman, warble as a pop star, or fuck a few older guys who were in a position to help his career—to move his fortunes forward. He was born David Jones in 1947. There was, on his mother’s side, a history of mental illness; an older half-brother was institutionalized and eventually killed himself. He played in bands from a very early age, notably with a friend, George Underwood, who in a passing schoolboy tiff punched David, inadvertently damaging his left eye permanently. (The pupil was left enlarged, giving Bowie’s eyes both an unnerving cast and the illusion that they are different colors.) Besides the bands, he trained as a mime and appeared in underground plays. He worked as a commercial artist and joined a freethinking art collective. He got a publishing deal. In an early media spoof, he made his way onto television as the founder of an imaginary group purportedly bringing attention to harassment visited on youths with long hair.

The years of false starts were ameliorated somewhat by the fact that his striking looks and status as an up-and-coming underground star made the sating of an extravagant sexual appetite quite easy to accomplish. Bowie had affairs with women and men and told interviewers he was gay—this at a time and place, it need hardly be said, where such declarations were not generally a step toward career advancement. In 1970, he married the colorful Angela Barnett—a worldly American and a provocateur in her own right, with a Kewpie voice and a formidable ego—and maintained a flamboyant, ultimately destructive open marriage with her for a decade. In 1971 the pair had a child, Zowie, now known as Duncan Jones, director of the film Source Code.

The evidence is clear how hard he worked during this period, his facile and lithe mind whirling. He loved music of all types, notably the conventions of musical theater and the hyperdramatic excesses of the divas of the previous generation. He had a thing for science fiction; he seemed to believe that there was little wrong with society an alien invasion of supermen couldn’t fix. He read—or at least affected to read—confrontational social theorists like Nietzsche, who had a thing for supermen too. He developed an unaccountable liking for the over-the-top caterwauling of Anthony Newley (a lugubrious, highly unironic British balladeer with a ludicrous drawl of a voice) and Jacques Brel (a similarly overdramatic Belgian chanteur) and, since he was half a musical generation younger than that stellar sixties era of rock-and-roll innovators—the Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks, Clapton, the Yardbirds, and many others—he consumed their influences as well, from the dance-hall schlock so beloved of Ray Davies and Paul McCartney to the tough R&B of the Stones and the Yardbirds.

His first two albums were largely undistinguished mélanges of pop and folk conventions. Yet he also crafted a fluke hit, “Space Oddity.” This came out around the time of the Apollo 11 moon launch in 1969 and made the charts in Britain. His third album, The Man Who Sold the World, demonstrated the muscle of a core of strong collaborators, among them Visconti and guitarist Mick Ronson, and contained the first-rate title song, anchored with a pair of de-amplified riffs: a warped, intriguing one at the beginning, and a positive, ascending, subtle one for the chorus.

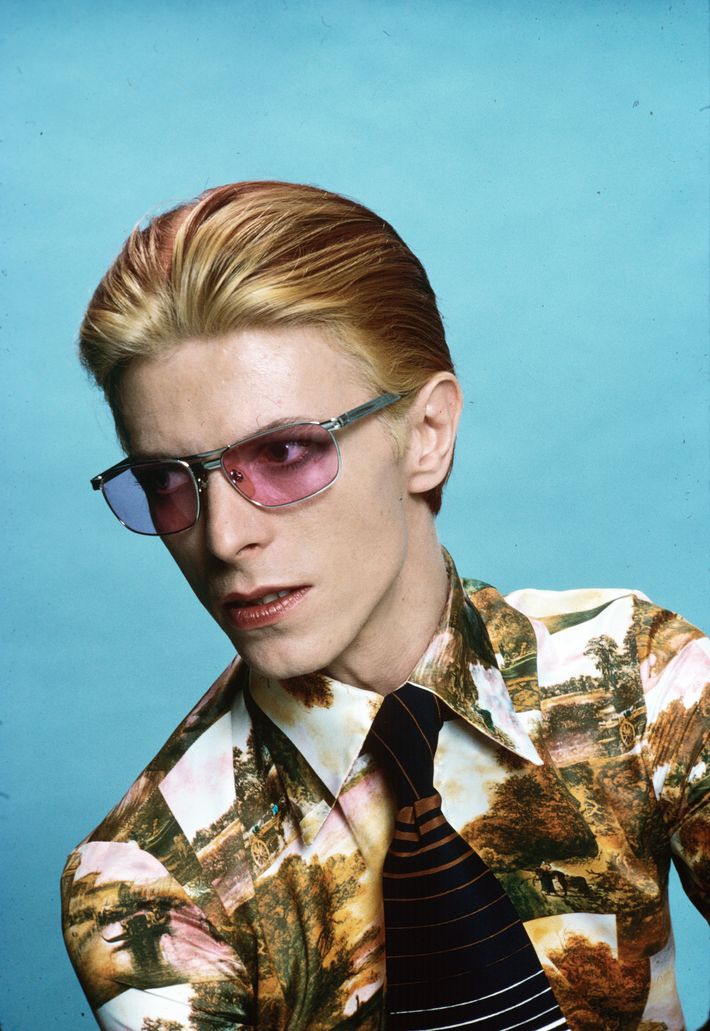

What followed were three (or six, or nine, depending on your level of fandom) albums that made Bowie arguably the most challenging and restlessly creative figure of the decade. Hunky Dory featured the artist on the front looking like a candy-colored Joan of Arc aglow in the light from the stake and on the back looking like Lauren Bacall. The song cycle between these portraits was a musical recalibration. There was no heavy metal, and nothing that could be pigeonholed as folk. Instead, he had somehow assembled his influences into a sparkling set of pop and rock tunes—genres that he thereupon thoroughly subverted through the different guises, and then guises within guises, from which he sang the songs. Take “Oh! You Pretty Things.” The jaunty warblings of a new father (“Don’t you know you’re driving your mamas and papas insane?”) and the irresistible melody hide cluster bombs. The first verse ends, “All the strangers came today / And it looks as though they’re here to stay.” It’s sung with menace; this innocent song about children is really about an alien takeover and his old friends, the Nietzschean supermen. The album continues with tribute songs to both Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol and a hat tip as well to the Velvet Underground. “Queen Bitch” is a pansexual cocktail; a squeal of betrayal and jealousy from a gay netherworld (“She’s so swishy in her satin and tat / In her frock coat and her bipperty-bopperty hat”).

Donning his Newley hat, Bowie warbles through “Changes,” showing that sometimes an artifice can produce an unconventionally beautiful song about life and indecision. And then there is “Life on Mars?,” in which the Beatles’ “She’s Leaving Home” is blandly set to the chord changes of “My Way” and reimagined by a transvestite sci-fi fan who holds mass culture in contempt. Its grandiose visions, lancing aperçus, shattering strings, and canny musicality define a work of art. It is a portrait of a young woman at odds with her parents, apparently after a love affair, perhaps even a pregnancy (“Her daddy has told her to go”). And yet Bowie’s eye, while sympathetic, is pitiless: “It’s a god-awful small affair, to the girl with the mousy hair.” She tries to escape to the movies, only to find brutality and senselessness onscreen, a moment of cultural betrayal captured in a shocking, almost hysterical melodic leap.

Then came The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. It’s a concept album with Bowie’s greatest character. The story: The planet has five years to live, and an alien comes to Earth in the guise of a rock star. Something like hilarity ensues, but in the end, Ziggy, despite some guitar chops and, so we are informed, a large cock, finds that negotiating stardom is not easy. Bowie’s affinity for musical theater serves him well; like any great stage composer, he can write the perfect song for each beat in the narrative. Ziggy’s onstage prowess, his strangeness and his talent, are captured in “Moonage Daydream,” marked by a coursing, unforgettable guitar solo by Ronson. “Starman,” in turn, captures the star’s aching fan base, the tension building through each verse, until it’s broken by an urgent beeping, lifted from the Supremes, leading to the chorus, which has another great emotional melodic leap, this one stolen from “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” “Suffragette City”—an unbridled portrait of out-of-control groupiedom—barrels by with a Stonesian roar and orgasmic cartoonishness, bracketed by the stark grandeur of the theatrical summation, “Ziggy Stardust,” delivered soberly by one of the Spiders, and then “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide,” Ziggy’s rococo farewell.

Ziggy Stardust and the two albums that follow largely defined, apotheosized, and then, finally, put to rest glam rock. In Great Britain, then as now, Bowie is viewed as a star of the first rank. With the Beatles gone, and others drinking and drugging themselves to death, rock had become dour. Bowie was mainlined phosphorescence. On the BBC, a resplendent Bowie, saturated in color, sang “Starman” and, as the chorus swelled, draped his arm around Ronson’s shoulders and sang, “Let all the children boogie.” It was a portrait of decadent complacency that sent an electric arc through the youth culture. Soon after, photographer Mick Rock captured an indelible shot of the singer on his knees in front of Ronson, seeming to mouth the front of the man’s guitar. It was a place even Mick Jagger could not go. In the U.S., Bowie was viewed with a little more distance; his sexuality was confusing to lumpen rock fans; his mismatched, glittering eyes and jagged teeth made for a disturbing presence. “Space Oddity” was a hit here in 1973, but the curious, checking out Ziggy or Aladdin Sane, would have found themselves in a sex, aliens, and rock-and-roll landscape they weren’t anticipating. The Ziggy Stardust tour played to empty houses in the hinterland. Not even “Rebel Rebel” made it to the U.S. Top 40. Bowie got respectful reviews Stateside but, scandalously, never placed an album in the top ten of the Village Voice’s “Pazz & Jop” critics poll.

Through Hunky Dory; Ziggy; its successor, Aladdin Sane; and even in his final descent into glam-rock sci-fi pervitude, Diamond Dogs, Bowie’s logorrheic lyricism is addled but quite frequently surpassingly beautiful—“I gazed a gazely stare,” “The stream of warm impermanence”—and hilarious: “This mellow-thighed chick just put my spine out of place.” Bowie finds, now and again, true theatrical poetry: “Time takes a cigarette,” Ziggy observes, “and puts it in your mouth.” In later years, Bowie said that he tried “cut-up writing,” and even did so for the camera, but this is much less interesting than his deliberate amalgam of stage and street slang, louche characters (the Cracked Actor, Jean Genie, the Thin White Duke), gay snarkiness, genuine feeling, and drama, all loaded with allusive time bombs.

There was one subject, in particular, dear to the man’s heart. An obsession with stardom and its discontents bubbles out of Bowie’s work. There’s a familiar lilt to the title track to Aladdin Sane. It’s hard not to take the character as another of Bowie’s proto-stars. “Who’ll love Aladdin Sane?” he sings—and then, “Who’ll love a lad insane?” Those double meanings pair the images of his dead, mad half-brother and the rock star, the lonely, loony figure onstage. Then we recognize the music—a lift from “On Broadway,” the classic Brill Building cri de coeur of the undiscovered star. And what are cracked actors, after all, but rock stars? (The words are almost anagrams.) The pretty things in “Oh! You Pretty Things” are kids and alien supermen, sure, but also a new generation of would-be stars, “driving your Mamas & Papas insane.” And finally, as every student of the music knows, the dreadful and implacable coefficient of stardom is ticking time, another scab Bowie picks at. “He’s waiting in the wings,” he notes.

Bowie fought it. After his U.S. tour, Ziggy and the Spiders hit London’s Hammersmith Odeon as conquering superstars. At the end of the show, Bowie announced that it would be the last they’d ever play. He didn’t tell the band beforehand.

Behind the scenes, Bowie’s icy world was cracking. Turns out—yawn—he was a coke freak: He talked like a fiend, embarked on grandiose visions for theatrical staging he couldn’t afford, periodically announced his retirement, surrounded himself with bodyguards, and made ill-advised business decisions. He allied his fortunes with a flamboyant manager, Tony Defries. Together, they made Bowie a star and a lot of money but managed to spend all of the latter while accomplishing the former. The cocaine dropped the star’s weight; he became drawn and brittle and lapsed into paranoia. A hilarious Rolling Stone cover story in 1976 found a young Cameron Crowe tailing Bowie around as he peeked nervously for bodies falling out of windows and blurted out lines like “I will never ever tour again” and “I think I might have been a bloody good Hitler.”

Thus began part two of Bowie’s classic period. He took the red dye out of his hair and created a sound he called “plastic soul.” Young Americans featured the manic, extravagant title song, a rousing statement of identity for a new generation adrift in a post-Watergate hellscape. A studio riff cooked up by a new guitarist, Carlos Alomar, provided Bowie and his friend John Lennon a foundation for a collaboration that unexpectedly gave the now-veteran star a U.S. No. 1 hit, “Fame.” Station to Station’s epic title track, with its haunting arrangement and clanking studio noises, is the first indication that Bowie was moving away from traditional songwriting and into a realm of pure sound, even as “Golden Years” gave him another clean hit. Station to Station, like Young Americans, remains immensely charming and listenable to this day. They moved Bowie away from a bisexual alien netherworld and into a more gracious and magnanimous realm of hypersophisticated soul-drenched pop.

It is not always appreciated that, to some, Bowie’s artistic and spiritual generosity was boundless. He wrote a hit single, “All the Young Dudes,” and produced a hit album for a band he loved, Mott the Hoople. Bowie also idolized the Velvet Underground. (Amusingly, the first time he saw the band, he sought out Lou Reed and talked to him enthusiastically after the show. Only later did he find out it was actually Doug Yule.) He ultimately became friends with Reed and produced Reed’s classic Transformer album. On it was a signal work, Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side,” surely the oddest and most obscene top-twenty hit of the era. Another charge was Iggy Pop, whose drug use had taken him to just this side of the gutter and who was eventually institutionalized. Bowie’s concern for Pop was genuine and spanned decades. He grabbed his friend and headed off to Europe, which would be the setting for the revivification of Pop’s career, via the albums The Idiot and Lust for Life, as well as Bowie’s next three releases, Low, “Heroes,” and Lodger.

Eventually settling full time in Berlin with Pop, Bowie teamed up with Brian Eno, who in the years since he’d left Roxy Music had been experimenting with sound, guitar, and production techniques. With his help, Bowie began to build albums in the studio, creating lulling slabs of sound and occasionally adding ever more oblique lyrics. Today, the albums sound somewhat dated, with what in the end is a muffled production undercutting the sound experimentation. Bowie’s singing is more than a bit affected as he declaims over prancing backing tracks. The albums are hailed as experimental landmarks and—with their sometimes angular, mannered tunes—credited with kick-starting the New Romantics movement as well. That’s fine. But when a rock star is being credited with “creating soundscapes” instead of, say, “writing some of the best songs of the era,” it should be noted that the terms of the debate have been changed significantly. In the end, though, as the title track of “Heroes” demonstrated, Bowie still could create a masterpiece, an indelible, timeless portrait of love in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. “Heroes,” perhaps because of its production, unusual for the time, wasn’t played much on the radio in the U.S., but has of course in the years since become arguably Bowie’s best-loved song.

Which brings us to the Bowie who, so many years on, is the only Bowie a generation or two of music fans know. Out of whatever motivation, he decided to write a group of slight pop tunes and turn them over to Nile Rodgers, the auteur behind the late disco juggernaut Chic, who produced Let’s Dance. The result was three big U.S. pop hits—“Let’s Dance,” “Modern Love,” and “China Girl.” Bowie’s fans applauded the definitive U.S. commercial success that had so long eluded him. But there’s little of substance on the album besides the hits. Lyrics like “Put on your red shoes and dance the blues” don’t help.

But if Bowie had intended to remake himself permanently as a purveyor of pop bonbons, he wasn’t able to maintain that momentum. And, curiously and somewhat abruptly, his ability to record a compelling album thereupon left him. He remained exceedingly handsome and well liked. But so many years on, we look back to survey Tonight, and Black Tie White Noise, and Never Let Me Down, and Heathen, and—what am I forgetting?—oh, yes, Reality, Outside, Earthling, ‘Hours …’ What do we find? That Bowie lost the spark that once made even his failed experiments so interesting. In place of innovation are his exaggerated singing, various attempts to remain musically relevant, covers no one had asked for (Cream’s “I Feel Free,” the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows”), and more soundscapes. He toured periodically until an indulgent, flatulent outing called the Glass Spider Tour was widely mocked. Tacking to avoid these headwinds, he formed what was supposed to be a real rock-and-roll group, which released an immediately forgotten album under the terrible name Tin Machine. The momentum of this was halted by another Bowie solo tour, which was stripped down and designed to be remunerative; it was, he said, the last time he would play his hits live. Watching from backstage at a shed in a Chicago suburb at the time, I remember thinking it was the first time I’d ever felt that Bowie was insulting my intelligence. Then came Tin Machine II.

But he was innovating in another way—an experiment with a financial maneuver that became known as Bowie Bonds. Bowie got an up-front payment of some $55 million against the earnings of his back catalogue. Among other things, the money allowed him to reclaim full ownership of the songs his former manager still had an interest in. If it was a cash-out, he did it at the top of the market, in 1997. As the millennium dawned, a rough beast named Napster slouched into view; the bottom fell out of the music industry, and Bowie Bonds went south.

He became more friendly and transparent with age, even appearing in corny stuff like the A&E network’s Live by Request series. Since his heart attack, he has appeared only infrequently and hardly at all over the past five years. Rumors of unspecified health problems keep coming up, though Visconti in recent interviews has said the singer is fine. If Bowie does indeed perform some shows to accompany the release of The Next Day, fans will be able to get a close look at him to see if he’s truly frail—or just a sixtysomething who’s had a heart attack taking it easy and helping to raise his second child. (A daughter was born in 2000 with his second wife, the model Iman.)

Bowie retains enormous goodwill. After dabbling in serious acting years ago (The Man Who Fell to Earth; Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence), he appears once in a while in some incongruous TV show or movie (The Prestige, Extras). At the big rock charity events, he is capable of reminding everyone of his unparalleled capacity to create a dramatic moment. At the Freddie Mercury tribute concert in 1992, he and Annie Lennox joined together for a version of “Under Pressure” that thrillingly captured both stars’ detached theatricality. A decade later, at the post-9/11 Concert for New York City, he opened the show, sitting on the floor cross-legged, playing some tiny electronic keyboard. Dabbling mournfully at a set of chords in 6/8 time, he made Paul Simon’s “America”—seemingly a bygone snapshot of a bygone America—suddenly relevant.

The new “Where Are We Now?” is a similar meditation on life made suddenly fragile. “Fingers are crossed, just in case,” he sings. His memories, he tells us, are like “walking the dead.” In the video, the star looks, shockingly, quite old. It’s a brave performance, reminiscent in certain ways of his heyday—and isn’t old age a mask as well? The memories of the stars from the sixties and seventies are formidable. They were inventing not just themselves but a new world. In it, they roamed like mad princelings, fucking just about anything that moved and taking in all it had to offer. Isn’t it unfair to expect them to accomplish new revolutions? He’s not the only one of his coevals who, so many years on, look back on a career comprising, in crude terms, a decade of vivid achievement and then one, two, or three more of far lesser work. But Bowie will also always be the person who, just when it needed it, injected something comic, meaningful, and candy-colored—something disturbingly and delightfully sexy—into rock. He showed us there was life on Mars.

*This article originally appeared in the March 4, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.