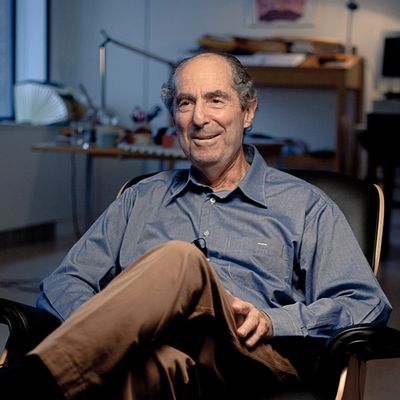

Philip Roth: Unmasked, the latest entry in the long-running American Masters series, arrives just after the Newark-born authorÔÇÖs 80th birthday. The documentary, premiering on PBS tonight, is fascinating for its relatively unmediated portrait of the normally reticent Roth. Yet, as written and directed by French documentarian William Karel and Italian journalist Livia Manera, it is a deeply puzzling and contradictory piece of filmmaking. Fans of the author (and even critics) will likely find something of value in RothÔÇÖs surprisingly direct statements on his life, work, and mortality. And yet everything surrounding those moments seems to have been placed there by filmmakers uninterested in venturing past the surface or in exploring what their subject is actually saying.

Watching the film, for which Roth sat for ten hours worth of on-camera interviews at his homes in Manhattan and rural Connecticut, is a bit like being a fly on the wall during a Paris Review Writers at Work interview. Roth works seven days a week, he says, spending one year on short books, two or so on longer ones. For him, the chief question when beginning a book is Where should I lift the curtain  to begin the story? And, as he says, its never worth shielding yourself from criticism  too much. Theres something to be gained from getting comments from friends on drafts of his novels. Even if I think theyre wrong. The filmmakers linger lovingly (perhaps too lovingly, and too often) on shots of Roth in the midst of composing  here his mouth drops a little, there he half-smiles as he revises a line  and you can almost see his mind working.

Intercut with these scenes are a series of talking head commentators  and distinguished ones at that: novelists Jonathan Franzen, Nicole Krauss and Nathan Englander; New Yorker writer Claudia Roth Pierpont; and actress and close Roth friend Mia Farrow. Its an odd, motley bunch, like the filmmakers either put out a bunch of feelers and came up short or just went with the first half dozen people they could find. At one point, Farrow describes Roth as there, rock solid, as a friend. Great. Shrug. Good for her. The trio of novelists come off better, but werent Michael Chabon or Gary Shteyngart available? They would have been even more appropriate choices and possibly more entertaining. Still, Krauss, who gets more than her fair share of screen time, is the sharpest of the chorus, stating, We dont go to literature for moral perfection, we go for moral ambiguity  And I think that is Roths territory.

The ability to work in the gray zones is definitely one of RothÔÇÖs strengths, but the film alternates between two stark approaches: the incurious ÔÇô not addressed in any way are the many, many criticisms of his work as misogynistic or, really, anything potentially negative beyond the flack he received from the Jewish community for his early work, most notably his first story in the New Yorker and PortnoyÔÇÖs Complaint ÔÇô and the contradictory. Given that most biographies, filmed or not, that involve the participation of the author end up taking it light on their subject, itÔÇÖs the latter thatÔÇÖs most confusing. The film opens with RothÔÇÖs statement that he has ÔÇ£two great calamities to face: death and a biography. My only hope is that the first comes first.ÔÇØ What follows? A 90-minute biographical film. Ironic/funny? IÔÇÖm unsure.

Later, we find out that Roth dated many women throughout his time in college ÔÇô by the testimony of Jane Brown Maas, one of his college friends, he dated only the most attractive women at Bucknell. And yet, by his own testimony, ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt have success, I had what everyone else had, which was nothing.ÔÇØ And yet, and yet: His old friend insists that PortnoyÔÇÖs Complaint, his groundbreaking ode to masturbation as a palliative for Jewish-American sociopolitical discomfort, couldnÔÇÖt possibly have been inspired by his college days. Roth lists many books in which sexual activity is almost absent ÔÇö and yet the film implicitly portrays him as a sex writer, foregrounding the great success of PortnoyÔÇÖs Complaint ÔÇö and revealing that one of his favorite lines from JoyceÔÇÖs Ulysses is ÔÇ£at it again,ÔÇØ uttered by Leopold Bloom as heÔÇÖs fondling himself while watching a girl playing on a beach. Roth is as interested in sex as anyone else is ÔÇö and why shouldnÔÇÖt he be? Yet, sex is, as he puts it, ÔÇ£a vast subject,ÔÇØ one among many, and the fact that it is focused on so much here, and comes up repeatedly, is lazy ÔÇö nothing we havenÔÇÖt heard about Roth before.

The documentary isnÔÇÖt any less problematic when itÔÇÖs describing RothÔÇÖs relationship to Jewishness. He states, from the outset, that he would rather be considered an American writer than a Jewish writer, that he wrote about Jewish characters simply because that was in his background. As he says, ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt write in Jewish, I write in American.ÔÇØ And yet, one recurring thread of the soundtrack sounds vaguely like Klezmer music, complete with a lilting clarinet. What are we to make of this? Are the filmmakers being ironic? If so, the irony doesnÔÇÖt work; the film doesnÔÇÖt juxtapose these elements in an overt enough way, so the irony floats away wispily.

Is it possible to judge entries in the American Masters series too harshly? My colleague, VultureÔÇÖs TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz, tore to shreds the seriesÔÇÖ recent entry on David Geffen, while also pointing out the seriesÔÇÖ original sin:

Most American Masters specials fawn over their subjects. This is partly because the series doesnÔÇÖt profile people it doesnÔÇÖt deeply respect (why should it?), and partly because it prizes artistsÔÇÖ work over their lives and wants to explore it with definitive thoroughness. The best way to be definitive about an artistÔÇÖs work is to gain access to the artistÔÇÖs inner circle, private correspondence, and personal material. You canÔÇÖt get all that without depicting the subject sympathetically, and sometimes deferring to his or her wishes when deciding what to dwell on and what to gloss over. I canÔÇÖt think of any American Masters special about a still-living subject that wasnÔÇÖt a love-fest.

That immersion that Seitz refers to above, that burrowing in, may have taken place during the research project ÔÇö we know, at least, that Manera read all of RothÔÇÖs books before starting the project. However, it seems also that a deeper immersion in RothÔÇÖs time and place, or at least a grappling with the complexities of his life, did not happen. So, in the end, we get a half-baked and suspiciously off-kilter portrait of a man whoÔÇÖs smarter than the film in which he appears.