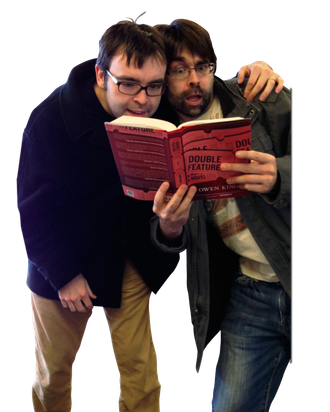

This week, Joe Hill (born Joseph Hillstrom King) released his fourth book, a 700-page horror story called NOS4A2. In March, his brother, Owen King, published his first novel, Double Feature, about a young filmmaker grappling with disappointment after his first movie falls apart. The two books couldn’t be more different, but what their authors have in common, of course, is that their parents are Stephen and Tabitha King. Vulture spoke with the guys about their writing approaches, how they’ve learned to evade (and live with) their parents’ shadows, and who beat up whom as a kid.

Owen, aren’t you doing an event in Joe’s area?

Owen King: Yeah, I’m doing something at River Run Books in Portsmouth [New Hampshire].

Joe Hill: I’m sorry I’m not gonna get to see it: He’s doing a scene that involves an extended description of masturbating with dish soap, and I’ve got my boys and I felt like that might be a tough one for the 10-year-old.

OK: Yeah … I was actually just racking my brain about something else I could read.

JH: I’m imagining my 10-year-old saying, “Daddy, why is he doing that to his foreskin?” Those are the kinds of conversations I’m uncomfortable with at this stage in my parenting.

You’re reading the phone-sex bit from Double Feature?

OK: Yeah, it plays really well. I did it in Oxford, Mississippi, to this auditorium of genteel, elderly Southerners, and as soon as the guy starts wanking off — they’d been laughing, and then this silence descended. I was like, Oh, they hate this and I am dying up here right now. But there was nothing I could do, I had to keep going, and then they started laughing again and it was okay. But I think that goes to show, jerking off is funny everywhere.

JH: When [my book] Heart-Shaped Box came out, I was really nervous. I did a hometown reading, 120 people, and it was a bit profane, the scene I was gonna read from, and I just decided I was gonna go for it. And so the girlfriend is talking to the rock star and she says, “You’re real sympathetic, you know that?” And he says, “You like sympathy, go fuck James Taylor.” The second I said that, these three little kids popped up in the crowd. I swear, they grew like mushrooms after rain — they weren’t there before I said it. After that I was pretty easy in my heart about reading directly from the story even if it has some upsetting material. I don’t mind if my 10-year-old finds out about obscenity and upsetting concepts, as long as —

OK: — as long as you’re not present.

JH: Right. As long as I’m not around and I can claim innocence.

Do your sons read your graphic novel Locke & Key, though, Joe? It is a comic …

JH: I told my kids under no circumstances were they allowed to read Locke & Key, so naturally they read it when I wasn’t around. Starting with the youngest, who read it when he was 8. And it was really not appropriate for him at all.

OK: Did they like it?

JH: Yeah, they like it a lot. My oldest boy thinks the comic speaks poorly of my moral character.

What are you each trying to explore or explain in your work? What are the subjects for each of you? Family, dysfunction, death?

Both, in unison: Masturbation.

OK: With Joe it’s metaphorical; with me it’s literal. [Laughs.] I think I always wanna write comedy because that’s what feels truest to me, it feels closest to life as I know it, so that’s what I want to reproduce. But I don’t know if I have a subject. For me the easiest thing to figure out is the story I want to tell, and the hardest thing is to figure out the voice that’s gonna tell it. And that’s why I finish very little. I had somebody ask me the other day, “What do you do when you get stuck?” And I told them, “I quit.” I shit-can that story and start something new. That’s my method, that’s why I only finish, like, one thing out of every ten.

JH: What’s your ratio of pages you write to pages you publish?

OK: Ah … it’s so horrible to even consider that. It could be something as crazy as, like, 50 to 1. Twenty-five to one.

JH: I mean, I know that I wrote hundreds of pages of NOS4A2 that I threw away, especially in the early go. While I was trying to figure out who the bad guy was, I took several wrong detours and wrote hundreds of pages of versions of Charlie Manx that no longer exist. And in between Heart-Shaped Box and Horns I tried my hand at two or three different novels that didn’t feel right that I ended up shit-canning.

Joe, you’re 40, and Owen, you’re 36. Your dad had more than twenty books published before he turned 40. Is there any sense of frustration that you don’t have that ungodly production speed?

JH: Our dad is a really unique figure in the history of American letters. With NOS4A2 it’ll have been four books in nine years, which feels like it is pretty prolific but isn’t in our comparison to our dad. I think compared to most working, professional American writers, Owen and I are both about as prolific as any of ’em.

OK: I think you’re more prolific.

JH: I think the best writer of our generation is David Mitchell. And he’s written five books since 1999, which feels to me like it’s pretty prolific. But if you were to compare him to Lee Child, Stephen King, or Elmore Leonard, David Mitchell would look like he writes at an agonizing pace. The other thing is, and maybe it’s because our dad has written so many great books and is so successful, but I think Owen and I … I don’t want to release a bad book. I’m really at pains not to rush something and release it.

OK: I wanna go faster, but I’m obsessed with getting it right. It’s very hard to let go.

JH: I have a terror of including one scene, even one scene, in an extended work that feels like it’s just spinning its wheels. ‘Cause my terror is someone will put the book down and walk away to watch something on YouTube and never come back. The other thing is, there’s a part of my mind that thinks if I could work faster I could achieve X or achieve Y or whatever it is. But, you know, the part of me that actually writes the stories doesn’t seem interested in achieving X or Y. It seems really interested in getting the sentences right on that page. And if it takes three days to do that instead of three hours, or three weeks instead of three days, then the creative part of me is happy to take that time. And I’ve never been able to be any different.

Your dad’s been at this a lot longer, too. That must make a difference.

JH: I think with our dad and a few other writers who have achieved almost the highest level of success you can have in publishing, you tend to find that there is a machinery around them that really streamlines everything toward getting work done. When your favorite writer is slow to produce, my thinking about it is usually that they’re probably juggling a lot of other balls. It’s highly unusual for a novelist to have the kind of machinery around them that, say, a director like Steven Spielberg has, where all the rough edges of their personal life have been smoothed off to allow them to focus on doing what they do best and that only they can do.

How similarly or differently do the two of you work?

OK: Joe’s focused; he’s got a good work ethic — he’s everything that I’m not. There’s a lot more forward motion coming from Joe’s office than from mine, I think. We both work at it every day, like it’s a job, but he’s more confident.

JH: I don’t know if that’s true. I sometimes think Owen is more architectural about his work. The pieces fit together and there’s an almost perfect stitching there. In my case, if the story’s well stitched together, it’s always because I was able to do that after the fact.

OK: I think it’s almost impossible to edit something to death. I think you can make things better almost indefinitely.

JH: One of my heroes is Bernard Malamud. He wrote, I think, seven books, and it took him about seven to eight years to finish a novel. And every single one … his most minor work is an astonishing masterpiece. And I think that goes to show that you almost can’t revise enough. You can’t.

How did you decide to spend your life writing fiction?

OK: I hope Joe has a good answer, because it was never like I read a book and said, “That’s what I wanna do.” It was more like I loved to read, I liked to tell stories, I practiced; eventually, it started to seem viable.

JH: I don’t think there was exactly one aha moment. But you’d come home from school and Mom would be in her room clattering away on this tomato-colored typewriter and my dad would be up in his office working on a word processor with the glowing green letters on the black screen, and they’d both be making stuff up. So for myself, by the time I was 11, 12, I’d kind of absorbed the idea that you should spend a little time each afternoon making stuff up and eventually you’d be paid really well for it. I did get a formal rejection from Marvel Comics when I was 12 years old, on a Spider-Man story. It had a note scribbled across the bottom from the then-editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, and it was so illegible I was never able to actually read what he had written. So it’s possible he wrote, “Boy, this was the worst submission we read of all of them. This was dreadful.” But I didn’t know what it said, so I assumed it said, “This was great, keep trying.” It kind of felt like, “Yes! I’m on my way! It’s only a matter of time till I’m writing for Marvel!”

Was there a lot of emphasis in your home on the value of stories?

JH: We’ve always been a family that cares very passionately about books. Our dinner conversation was literary conversation, about this writer or this publication. And after dinners, often we would have a family book we’d go and read together, we would pass the book around. Our framework for thought was built around writers and stories and literary content and scene-creation — so in that sense the trade, not so much the art, but the trade, was constant conversation.

Did you ever rebel by rejecting that family culture?

JH: No, but I had a lot of stuff about changing my name.

OK: There was, like, three years in high school when everybody had to call you Ellis, right? Ellis Moriarty?

JH: Yeah. I remember that both my folks were a little bit concerned about that. I was thinking about not just using a pen name but legally changing my name. I was one of these kids who was really close to his dad, loved my dad, very emotionally tight, and yet at the same time I was very conscious that he was this huge, looming presence in the work of pop culture, and it’s very difficult to carve out a space. And I did have this idea about going into film or writing. I know Owen’s wrestled with this, and I know one of the ways Owen has dealt with it is by kind of taking a left-hand turn off the expressway and writing almost a completely different type of fiction.

OK: I mean, you want to be Stephen King’s son in your regular life, so where does your regular life meet your public life? It gets to be quite a knot.

Seems like it.

JH: It’s tough, too, because we’re both tremendously proud of Dad’s work. Above and beyond the fact that I love my dad and we’re really close and we talk every day and we’re like best friends and everything, I’m an enormous Stephen King fan. I love all of his books. I’ve read The Dead Zone, like, twenty times. But I think every artist faces this set of challenges. I think it was Malamud who said the artist’s first and most important creation is themselves. Your first work of art is trying to create an identity. And if you manage that first magic trick, then all the other works flow naturally from it. So on one level, it seems like Owen and I both had to wrestle with something, which is really exceptional and strange. On another level —

OK: — it’s pretty normal.

JH: I think it’s kinda normal! And you know something? Not only that: Every writer who is any good is the child of another writer. They may not be the child of another writer by blood, but literally the child of another writer. Our dad is the child of Richard Matheson, and has talked about that in very concrete terms. Jim Harrison is the child of Ernest Hemingway. Tobias Wolff, too. Michael Chabon says all fiction is fan fiction — that every writer, when they set out to write a book, sort of has these other books in their head that they adore, and they want their book to make people feel that way.

There’s also the fact, Joe, that by writing horror, you would’ve gotten likened to Stephen King as many times if you weren’t his son as if you were.

JH: I went into a bookstore once, back in the eighties, and the horror section was called “Stephen King.” And there were other books in it besides Stephen King. There was a Dean Koontz shelf and everything, but it was just kind of like, “Here’s Stephen King … and all the other people who wish they were Stephen King.”

OK: That’s why Joe’s situation is especially unique. He has a double shadow, being Stephen King’s son and then that the whole genre is “Stephen King.”

It seems like, even though you’ve got your own styles, I sometimes can’t avoid this “Stephen King did it!” layer of reading your work. A character has a St. Bernard and I think of Cujo. I read Gasmask Man and think Trashcan Man.

JH: NOS4A2 has a lot of Where’s Waldo? tricks with Stephen King. It was very intentional. I thought, Instead of running from the Stephen King stuff, I’m gonna run at it.

NOS4A2 feels like your biggest accomplishment so far.

JH: The whole book was an attempt to go larger than I had gone in the past and try to risk more. I had never written a book where I shifted perspective in characters. I wanted to do something that, instead of just covering a week, covered most of a life. I had never had a female protagonist. I wanted to really know who she was and how she came to be the person she is as an adult. Everything in NOS4A2 is larger. It’s my supersize meal.

Owen, Booth Dolan is this huge achievement of a character. Did you model him after Orson Welles to a degree?

OK: Booth works with Orson Welles, and Welles appears in a couple of scenes very briefly, but Booth is more like Vincent Price or Boris Karloff. He’s the poor man’s Orson Welles in a lot of ways. He has as much to do with Donald Pleasence or Malcolm McDowell, he’s that kind of B-movie actor, and his dabbling in filmmaking is sort of a happy accident for him. There were a few different things that inspired the book, and I certainly think one of them was that I love the movies of Orson Welles, and like a lot of other people, I’m just obsessed with all the things he didn’t make and all the things he tried to make. He spent twenty-odd years or more filming parts of stuff. Double Feature has a lot to do with lost films.

JH: Mentioning Chabon earlier, I think one of the things that’s interesting about Double Feature is its fixation on these characters who are haunted by the things they didn’t accomplish, and in that way it reminds me of Wonder Boys. That’s really about the horror of what you didn’t get done, all the things you thought you had in you that you never were able to deliver, all the promises you weren’t able to deliver on. I think that that’s one of these great tragic themes, and sort of a uniquely American theme.

Joe’s novel Horns is being made into a film starring Daniel Radcliffe. Suppose film adaptations happen for these new books: Who would you guys like to see playing your characters?

JH: In some ways, I don’t like to cast the books because I prefer for readers to identify that or come up with their own person. Hypothetically, though, just to throw a name out there: Jennifer Lawrence could play Vic as a teenager and also as a young mother.

OK: Every older character actor in the world would want to play Charlie Manx, right? It could be Christopher Walken or Paul Giamatti … Kevin Spacey would be great.

JH: For Booth, you have to have someone with a looming, massive presence, someone who distorts almost every picture he’s been in.

OK: If Kelsey Grammer was a larger man, because he’s got that Wellsian voice …

JH: Nooo, not Kelsey Grammer.

OK: John Goodman.

JH: John Goodman would be okay. Bill Murray would be absolutely the best.

What about Rick Savini, Owen, this indie stalwart character you’ve got? I was picturing John Hawkes until I saw your Grantland piece about Steve Buscemi and realized maybe it was him.

OK: I was thinking about Steve Buscemi, Paul Giamatti, John Hawkes is a really good one — Rick’s kind of an amalgam of all those particularly not-physically imposing character actors from indie movies.

Do the usual strains of sibling rivalry pop up between you two?

JH: I was bullied a lot. He was younger than me by five years, but he was massive and he had a streak of remorselessness in him that I didn’t have — I was very sensitive. I’ve never forgiven him for, in a wrestling match once, he tore my favorite Bob Dylan shirt right off my back.

OK: I just beat the shit out of him all the time.

JH: But most of our sibling battles, there wasn’t much there to begin with, and we left it behind when we were kids.

So no friction made its way into your lives as professional writers?

JH: I will say that when I read Double Feature — and I also felt this way about We’re All in This Together, Owen’s novella — I was kind of stunned and put back on my heels and also spent some time trying to figure out if I could have written those books. He’s my brother and I don’t expect people to take me at face value on that, but I laughed really hard reading the book.

OK: It’s easy to read Joe and just be a fan; I don’t feel competitive. We’ve written together a little bit, and when we write together we merge pretty seamlessly, but I don’t feel like our writing voices are that similar.

JH: I’m capable of feeling a kind of jealousy when I read something like Double Feature, but it’s a pretty happy jealousy. It’s not a resentful thing. I’m really psyched about how good it is, and that’s the kind of writing I aspire to. I read a book last year by Jess Walter called The Financial Lives of the Poets, and I loved how much it was about life right now, and there’s a lot of that in Double Feature. I sometimes feel like that’s something I would like to do more of in my own fiction, talk about the conditions of life as it’s being lived right this instant.

Does that happen with you in some way, Owen?

OK: I enjoy Joe’s books pretty jealousy-free because I just don’t think I could write anything like them. I read certain kinds of books and I think, God, you fucking beat me to it. I could just kill him or her for writing what should rightfully be mine. But with Joe’s books, I don’t do anything like that, so I can just be a fan, and that’s actually in some ways my favorite kind of reading, because I’m not thinking very much about how he did it. Whereas with those other kinds of books a lot of times I’m trying to figure out how they did it. Can I do something like that? Or, What’s the trick here? But with Joe I’m just a fan.