Warning: The following post contains spoilers for Breaking Bad, Dexter, Homeland, The Wire, The Sopranos, House of Cards, The Walking Dead, The Americans, Justified, Boardwalk Empire, Sons of Anarchy, True Blood, Lost, and Game of Thrones.

Rule 1:

Start with an anti-hero.

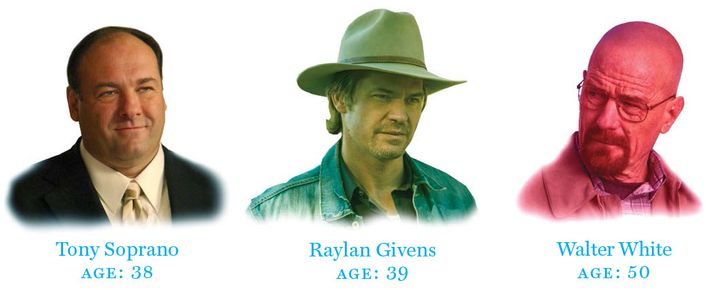

A. Make him middle-aged.

Anti-heroes between the ages of 35 and 55 can often be found leading lives of quiet desperation, tied down by two kids and a suburban home. These protagonists will encounter midlife crises, affairs, and pressure from characters both older and younger. Right now, as the economy continues to skid, a middle-aged person losing his edge isn’t a bad metaphor for a generation grappling with the fallout of the long-gone American Century. Try a guy who’s lost a bit of his mojo and who’s struggling to get it back: an avatar for boomers holding on to their golden age but aware of their mortality. (See Mad Men’s Don Draper, House of Cards’ Frank Underwood, Breaking Bad’s Walter White, Homeland’s Nicholas Brody, Justified’s Raylan Givens, The Walking Dead’s Rick Grimes, and Boardwalk Empire’s Nucky Thompson.)

B. Give him a health problem and a traumatic memory.

There’s a difference between anti-heroes and monsters: Viewers can understand and sympathize with anti-heroes, despite their awful behavior. So give yours an illness that could happen to anyone (see Tony Soprano’s panic attacks, Don Draper’s heart trouble, Nicholas Brody’s battle scars and PTSD, and Walter White’s cancer). Then flash back to his traumatic past to explain how he became such a mess (see Tony’s mom, Don’s whorehouse childhood, Brody’s eight years in captivity, and Walt’s business failures).

C. Make him great at his job.

Audiences don’t need to like an anti-hero, but they have to be impressed by him. They’ll excuse any affair or murder if a character is exceptional at something. So make him among the best in his field, be it advertising (Don Draper), meth cooking (Walter White), glad-handing (Nucky Thompson), serial killing (Dexter Morgan), or crisis management (Scandal’s Olivia Pope), and make his expertise part of the thrill of the show. He needs to be dizzyingly talented — but also not so good that he’s invincible. He needs to feel a competitive fear of legitimate rivals that drives him to more extreme actions and raises the dramatic stakes.

D. Make his business a microcosm of the American Dream.

Prestige TV needs to resonate deeper than your standard procedural about doctors, cops, or lawyers. The anti-hero’s occupation should put him in contact with a wide range of greedy and power-mad characters in a competitive, capitalistic field where there’s room to grow: drug dealer (The Wire’s Stringer Bell), mob boss (Tony Soprano), lawman (Raylan Givens), congressman (Frank Underwood). An intense, classic American workplace offers ways to ratchet up the tension and say something about bigger issues, like power, greed, and capitalism.

E. Give him a secret.

If he’s keeping something from his family — whether it’s his meth business (Walter White), affairs and stolen identity (Don Draper), an Al Qaeda plot to kill the vice-president (Nicholas Brody), or a desire to quit the KGB (The Americans’ Philip Jennings) — that gives you an easy, obvious handle on “the human heart in conflict with itself,” which Faulkner dubbed the root of all good writing. A secret also pushes the narrative: Eventually his spouse will find out and eject him from their home, upending what little stability he has left. Whatever he’s hiding, it’ll provide a launching pad into discussions about real marital problems, interior lives, public selves, and trust.

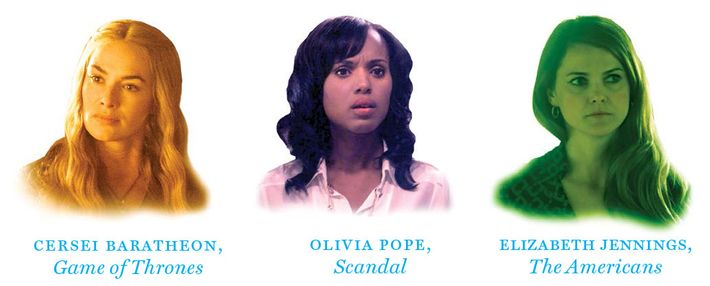

F. Make him a woman.

For nearly two decades, the dramatic anti-hero has usually been a man — but thankfully that’s changing fast. The Americans, Homeland, Scandal, Game of Thrones, and even dramas in comedy drag, like Enlightened and Girls, have given us compellingly screwed-up female protagonists who check all the necessary boxes. For example, on The Americans, suburban mom (A) Elizabeth Jennings was raped and abused earlier in life (B) and is a brilliant KGB spy in Cold War–era D.C. (C and D) who hides her secret identity from everyone except her husband (E).

Rule 2:

Give him a family.

What links most dark, Emmy-hungry dramas — from Mad Men, The Americans, The Walking Dead, and Breaking Bad to The Tudors, Downton Abbey, and Game of Thrones — is that, at their core, they’re really just shows about families. There’s often a spouse who serves as the show’s conscience (Carmela Soprano, Skyler White, Betty and Megan Draper, Jessica Brody); a rebellious, troublemaking daughter (Meadow Soprano, Sally Draper, Dana Brody); and a negligible, clueless son (A. J. Soprano, Walt Jr., Bobby Draper, Chris Brody, Carl Grimes). To raise the stakes and magnify the sense that the anti-hero will do anything for his family, give one of his kids a disability: On Sons of Anarchy, Jax’s child is born with a heart defect, and Breaking Bad’s Walt Jr. has cerebral palsy.

Rule 3:

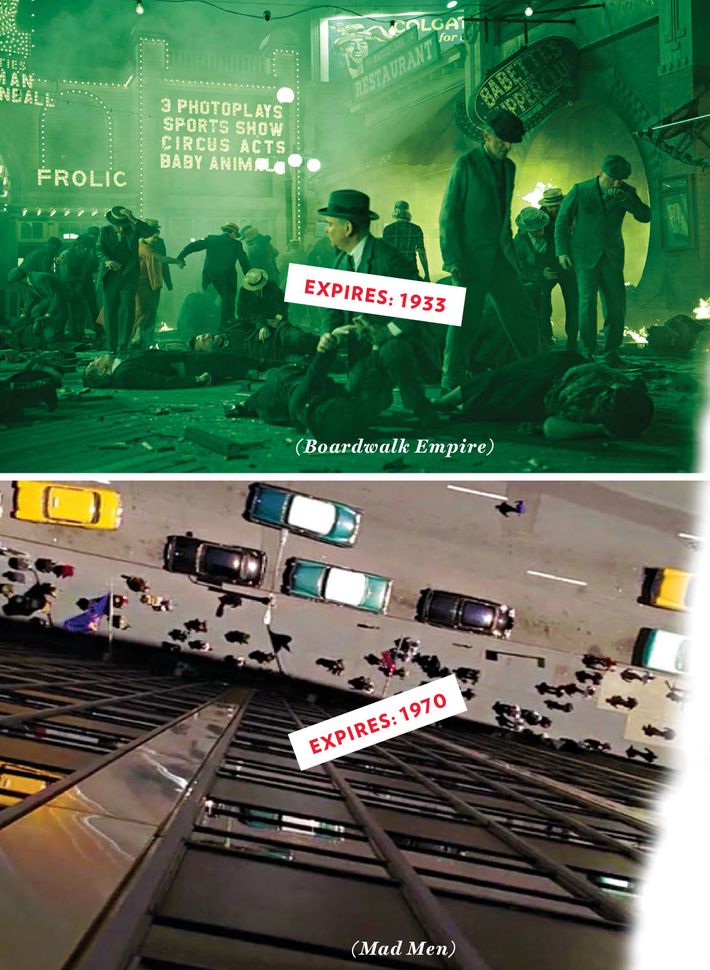

Set your show at the end of an era.

Let your protagonist embody some historical shift by thrusting him right into it: Prohibition-era Atlantic City (Boardwalk Empire), sixties Madison Avenue (Mad Men), post-Edwardian England (Downton Abbey), the Reconstruction-era West (Hell on Wheels). This gives the series a finite shelf life (typically six seasons) and a sense that the world is changing, not like some timeless, Simpsons-like Springfield, where there are no consequences because everything always stays the same.

Rule 4:

Give the hero a mentor or a protégé.

Almost every great prestige drama uses TV’s long-form potential to dramatize generational shifts. Whether on Madison Avenue (where Don Draper squares off against Peggy Olson) or at the CIA (where Carrie Mathison clashes with Saul Berenson), this conflict is key. There should either be an older, authority-figure mentor whom the protégé can buck up against (or who can be killed and later avenged), or a younger character who threatens the anti-hero’s sense of power and makes him feel obsolete.

Rule 5:

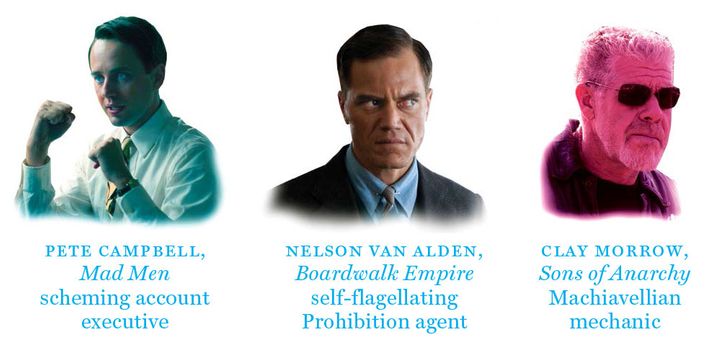

Add a nemesis with problems of his own.

So you’ve got a brilliant anti-hero — now write a villain who’s just as complex, potentially even more monstrous, and with motivations that are equally plausible. Think nasty opponents like Mad Men’s Pete Campbell, Sons of Anarchy’s Clay Morrow, and Boardwalk Empire’s Nelson van Alden. Or half-decent guys like Breaking Bad’s Hank Schraeder or The Americans’ Stan Beeman. The best villains, like Stringer Bell and Justified’s Boyd Crowder, often become fan favorites.

Rule 6:

Then write a bottle episode.

Narrative sprawl is great, but some of the best episodes in recent dramatic television have been minimalist two-handers: Mad Men’s “The Suitcase,” which pitted protégée Peggy Olson against mentor Don Draper. Or the Jesse Pinkman–versus–Walter White face-offs in Breaking Bad’s meth-lab episode “Fly.” These episodes distill the long story arcs of larger series into simpler generational clashes.

Rule 7:

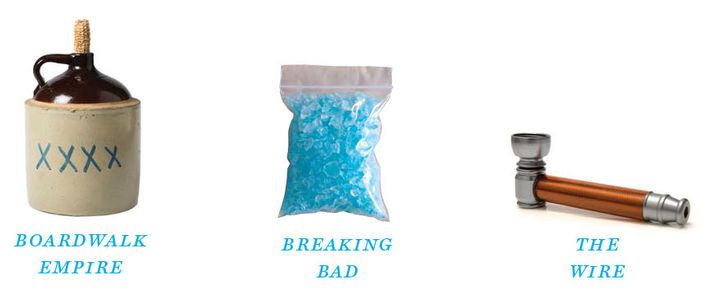

Put a drug at the center.

The illicit-substance trade is one of TV’s most durable metaphors for American capitalism, and many prestige dramas revolve around a drug, whether it’s alcohol (Boardwalk Empire), crystal meth (Breaking Bad), or crack (The Wire). This allows for sketchy supporting characters, outlandish violence, and heartbreaking, “butterfly effect” consequences for everybody along the distribution chain.

Rule 8:

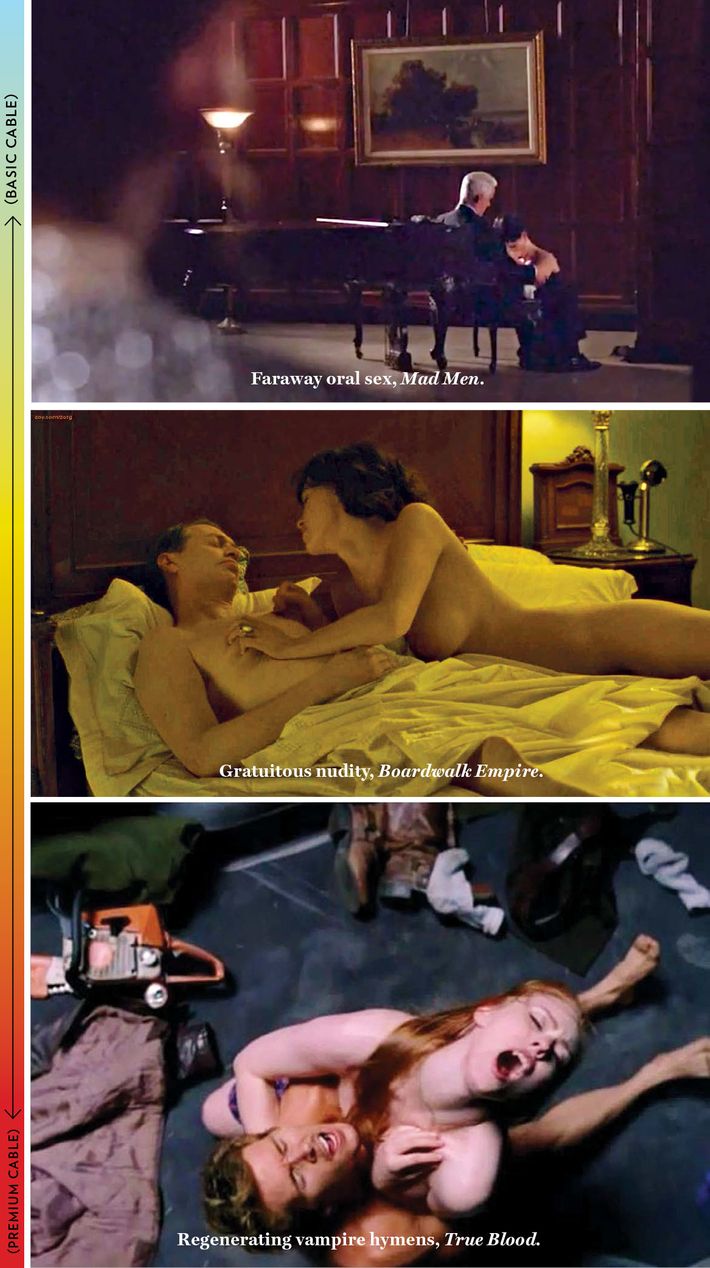

Sex.

Cable dramas need to distinguish themselves from broadcast fare, and sex is an easy way to do it. On basic cable, push the boundaries of what’s allowed (Roger Sterling’s blow job, witnessed by Sally Draper, on Mad Men). On premium cable, the sky’s the limit: At minimum, include plenty of gratuitous nudity (Game of Thrones’ wenches; The Sopranos’ Bada Bing Club, Boardwalk Empire’s Paz de la Huerta), then let your imagination run free. Everything from polygamy (Big Love) to sexual torture (Joffrey on Game of Thrones) to regenerating vampire hymens (True Blood) is fair game.

Rule 9:

Parcel out the violence.

As Hitchcock knew, suspense is in the anticipation of violence rather than the gore. Stage a murder in every episode, and you’ll end up with just another CSI-style cop show. In long-form TV, suspense should build over many consecutive episodes. On Breaking Bad, for instance, Gus Fring is an unrepentant sadist — but he rarely acts. When he does, slashing Victor’s throat with a box cutter, it’s utterly shocking. To show violence’s lasting consequences, try chopping off a body part (Ned’s head and Jaime Lannister’s hand on Game of Thrones, Robert Quarles’s arm on Justified, and Mad Men’s mowed foot).

Rule 10:

Every serious drama pilot must have at least two of these things:

A. A health scare.

The easiest way to make viewers forget they’re rooting for mobsters or serial killers is to stage a medical emergency early on: In the Sopranos pilot, Tony collapses following what he thinks is a heart attack. On Sons of Anarchy, Jax’s baby has emergency surgery. On Justified, paramedics rush to save Boyd after he’s shot in the chest. On Breaking Bad, Walt is diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer. On Dexter, Rita’s son, Cody, gets sick. On Boardwalk Empire, Margaret Schroeder miscarries.

B. A corpse disposal.

So many series premieres feature such scenes that it’s down-right eerie: On The Americans, the Jenningses soak a body in acid. Dexter disposes of a child molester’s corpse in the woods. On Boardwalk Empire, Eli dumps Hans’s corpse at sea. On The Sopranos, Christopher buries Emil. Hiding or disposing of a body (and not just killing somebody and running away) establishes the rules of your show’s universe: Actions have consequences, and loose ends must be tied — only to become unraveled later, when characters’ sins come back to haunt them.

C. A party scene.

A long-arc prestige drama usually requires a sprawling world of characters that’s large enough to sustain years of intertwining story lines. But how to introduce them all? Almost every great drama pilot has a party in the premiere — whether a birthday party (The Sopranos, Breaking Bad), funeral wake (Six Feet Under), countdown-to-Prohibition blowout (Boardwalk Empire), or royal feast (Game of Thrones). It puts characters in the same room and establishes the existing relationships, demonstrating the complex verisimilitude of the show’s world.

D. A huge explosion.

Nobody’s going to know that you have an impressive budget if you don’t flaunt it early. So blow up something big in the pilot. Like a warehouse (Sons of Anarchy), restaurant (The Sopranos), airplane (Lost), or church (Justified).

E. A demonstration of our hero’s superpower.

Remember Don’s genius Lucky Strike pitch (“It’s Toasted”)? Or how Carrie spotted Brody’s finger-tapping terrorist code? Or when Jack performed surgery on a fellow Flight 815 passenger? Each pilot moment established that the character was the smartest person onscreen. Audiences can’t help but aspire to that expertise, even if the script is rigged.

Rule 11:

Hit the books.

Scatter literary references like birdseed. If the show is great, fans and recappers will spend endless hours searching for hidden meanings, regardless of whether such meanings exist or your references cohere. And if an episode is iffy, overt symbolism will distract and give your show the patina of smarts. Why not name your prison “Emerald City” and call the show Oz? Why not cite Dante’s Inferno on Mad Men, along with The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and Frank O’Hara’s poetry? What does Leaves of Grass have to do with Breaking Bad? Probably not much more than Tom Sawyer or Animal Farm had to do with Lost.

Rule 12:

Let nobody be safe.

Killing main characters will keep your audience on its toes and telegraph your intention to take dramatic risks. And when you’re planning that big shocking death scene, try to schedule it for a season’s penultimate episode, to take some pressure off the finale. Rest in peace, Lane Pryce (Mad Men), Ned Stark (Game of Thrones), Mike Ehrmantraut (Breaking Bad), Donna Lerner (Sons of Anarchy), and Stringer Bell and Wallace (The Wire), all of whom met their ends in penultimate episodes.

Rule 13:

Don’t forget the comedy.

Follow the previous dozen rules and things will get bleak pretty fast. Be sure to give some occasional comic relief. Saul Goodman, Badger, and Skinny Pete help to lighten the mood on the otherwise pitch-black Breaking Bad. Mad Men needs Roger’s quips and Harry’s buffoonery. And even The Wire had its own comic catchphrase: Senator Clay Davis’s “Sheee-it.”

This article previously appeared in the May 20, 2013 issue of New York magazine.