Sarah PolleyÔÇÖs nervous, whimsical documentary Stories We Tell is further proof that this gifted actress and possibly more gifted writer-director does nothing easy ÔÇö and might even have a compulsion to make things harder than they need to be.

The film centers on PolleyÔÇÖs mom, ┬¡Diane, who died 23 years ago ┬¡(Sarah was 11) and maybe had an affair that maybe produced Sarah. As painful odysseys go, this oneÔÇÖs relatively straightforward: Did Diane or didnÔÇÖt Diane? LetÔÇÖs have a look at the DNA ÔǪ But in a blog post published on the National Film Board of Canada website the day of the movieÔÇÖs Venice debut, Polley confessed that ÔÇ£personalÔÇØ documentaries make her squeamish: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve seen some brilliant ones,ÔÇØ she wrote, ÔÇ£but they often push the boundaries of narcissism, and can feel more like a form of therapy than actual filmmaking.ÔÇØ More fascinating to her was the way her motherÔÇÖs story changed depending on who was ┬¡doing the telling: ÔÇ£So I decided to make a film about our need to tell stories, to own our stories, to understand them, and to have them heard.ÔÇØ

So Polley has gone meta ÔÇö exuberantly, entertainingly, with all her heart. She opens Stories We Tell with a quote from fellow Canadian Margaret AtwoodÔÇÖs Alias Grace, which sheÔÇÖs not so incidentally adapting for the screen: ÔÇ£When you are in the middle of a story it isnÔÇÖt a story at all, but only a confusion ÔǪ ItÔÇÖs only afterwards it becomes anything like a story at all.ÔÇØ This quasi-storyÔÇÖs quasi-narrator is SarahÔÇÖs father, a ┬¡transplanted British actor named ┬¡Michael, who is not only seen but seen ┬¡being directed by Sarah, who occasionally has him re-read more delicate passages about his wifeÔÇÖs ┬¡infidelity. ÔÇ£What do you think of this ┬¡documentary being made?ÔÇØ She asks each of her siblings in turn. ÔÇ£Are you nervous?ÔÇØ ÔÇ£A little.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs going to get worse.ÔÇØ It does get testy with one of PolleyÔÇÖs brothers, who evinces surprise bordering on indignation that Diane didnÔÇÖt abort her final child. ÔÇ£Thanks,ÔÇØ says Sarah, off camera.

A producer named Harry Gulkin, with whom Diane spent time in the seventies (when she briefly left her family in ┬¡Toronto to appear in a play in Montreal), tells Sarah that he rejects any version of events that isnÔÇÖt his. He says he needs to ÔÇ£control the story.ÔÇØ But so does Michael, who turns out to have written the narration he has been reading, and in which he refers to himself in the third person. ┬¡Toward the end of Stories We Tell, Polley holds on each of her subjects for a few beats, alone with his or her private memory, his or her ÔÇ£truth.ÔÇØ

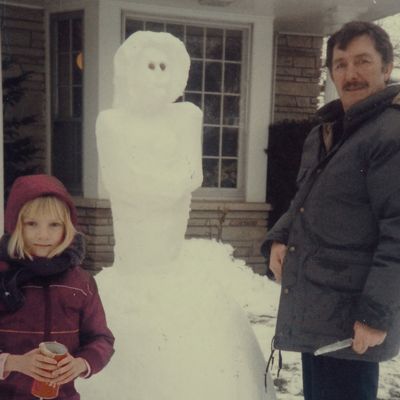

Between talking heads, thereÔÇÖs a lot of home-movie footage ÔÇö of Diane, Michael, the many kids, and Gulkin in Montreal. ItÔÇÖs amazing how much material Polley has access to given the cost of Super 8 film and relative absence of small home video cameras in the sixties, seventies, and eighties: These showbiz types must really have liked being photographed all the time! PolleyÔÇÖs footage is so splendidly ┬¡illustrative (down to tiny glances between Diane and the man who might be SarahÔÇÖs biological father) that you can even be forgiven for wondering if itÔÇÖs fake. But then you realize it canÔÇÖt possibly be fake. No actors could look as much like the younger versions of their real-life counter┬¡parts. You can see ÔÇö unmistakably ÔÇö┬¡ SarahÔÇÖs features in those of her on-screen mother. Besides, Polley would have to inform us that these were reenactments, wouldnÔÇÖt she? IsnÔÇÖt that what ┬¡documentary means? (Pssst ÔÇö itÔÇÖs fake.)

The meaning of documentary is extraordinarily fluid these days, of course, and by calling it so stylishly into question, Polley has earned a lot of affection from critics, festival-goers, and even fellow documentarians. Stories We Tell supplies a lot of talking points in the battle against the so-called truth of individual memory. But from my singular perspective, all this doc-consciousness has absolutely nothing to do with the story of Diane Polley. This is actually a rare instance in which ┬¡multiple perspectives dovetail neatly, in which thereÔÇÖs almost no ambiguity whatsoever about what happened and why. Polley didnÔÇÖt have to go all meta on us to justify our attention.

But I suppose she wouldnÔÇÖt be Polley if she didnÔÇÖt ÔÇö and now that I know that sheÔÇÖs (sort-of spoiler coming) half ┬¡Jewish, I wonder if itÔÇÖs not in her genes to try to mess up the seemingly orderly Wasp society into which she was born. In the eighties, she famously bullied her mom into putting her in showbiz, and then, when her teen stardom was assured, rebelled against Disney by showing up at a promotional event during the first Gulf War with a peace necklace. She got a couple of teeth knocked out during a protest. She dropped out of Cameron CroweÔÇÖs Almost Famous, probably because the role of the beatific groupie Penny Lane was too much of a passive waif. She was more in her element in Go, in which she was so pointedly, punkishly unlikable that many of us fell in love with her on the spot. Her accomplished first feature as a writer and director, Away From Her, was suffused with helplessness and ambivalence. Her second, Take This Waltz, was a leap ┬¡forward in technique: This time the ┬¡emotional ambivalence was right there in the filmmaking.

But does all that ambivalence ÔÇö for which another word is drama ÔÇö belong in her first documentary in this fashion? I suspect that Polley was so bent on not seeming narcissistic (or exploitative of her familyÔÇÖs privacy) that she didnÔÇÖt explore the effect on her of her parentsÔÇÖ irresolute marriage. She didnÔÇÖt explore what it meant for her to grow up with a dad who wasnÔÇÖt the least bit like her. The one story that Stories We Tell doesnÔÇÖt tell is hers.

This review originally appeared in the May 6 issue of New York magazine.