An hour with music producer Pharrell Williams at Jungle City Studios, up above the High Line and a wide array of new construction, feels like a minor form of time travel: He can connect an mp3 player to the console, turn the monitors up to jaw-rattling volumes, and play you pop music from the near future. These are the tracks he’s written for (or co-written with) various singers, beats he’s made for various rappers, a selection of sounds he’s crafted that could become radio fodder over the coming months. When we meet, he’s making adjustments to “ATM Jam,” a track for Azealia Banks’s upcoming album, and there’s plenty more of his work to follow. A tough-as-nails Jennifer Hudson song with a Rick James feel. A not-dissimilar piece for Miley Cyrus. A cut for Mayer Hawthorne that would sound like seventies smooth-rock kings Steely Dan even if we hadn’t just been talking about how much Williams loves Steely Dan, and even if he didn’t lean over afterward and say, “Sounds like Steely Dan, right?” A record with resurgent Destiny’s Child singer Kelly Rowland. And my favorite, an astonishing number from Kylie Minogue, which Williams might take extra pride in, because he makes a point of playing it without announcing the artist, then asks me to guess who’s singing: “That’s Kylie Minogue!” This is just the music he can share; somewhere beyond it lies the music he can only hint at (like new work with Beyoncé), and the stuff he can’t even discuss yet (he recently tweeted a photo of himself in a studio with Jay-Z and Frank Ocean).

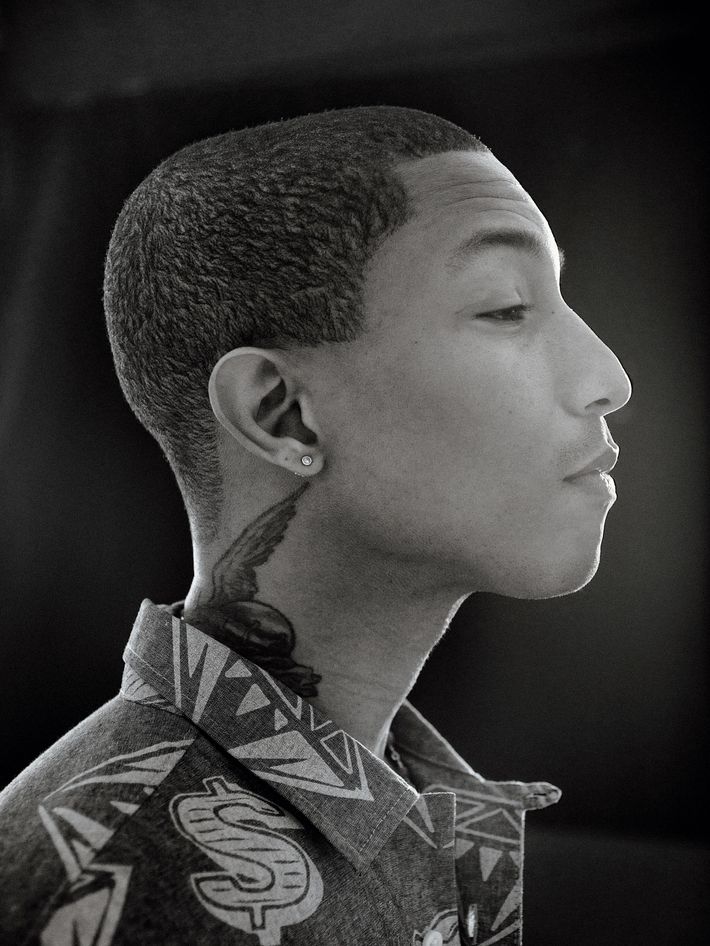

At 40 years old, Williams still has the lean, boyish air of a teenage skater, as though he could blend in with the kids in Union Square. But I’m guessing the metaphor he would choose to describe this listening experience would not be time travel; it would involve visiting a fashion house and browsing through next season’s clothes. He employs a whole lot of fashion analogies to explain what he does with music. They’re complex and thoughtful, featuring Mark McNairy, Rei Kawakubo, and different methods of setting Swarovski crystals, and they may be slightly informed by the marketing person who’s here to remind him to mention the tenth anniversary of his clothing line, Billionaire Boys Club—but the central thrust is that writing and producing songs for other artists is a lot like designing their clothes: “I think about the person, where they are in their life, what they’re going through. I think about what’s going to look good on their body. So I’ve got to put the right fabric, the right print, the right weight and feel. And then I’ve got to dress the window.” That Kylie Minogue song, for instance: Williams was inspired after Minogue, suddenly confronted by some other urgent matter, thought she’d be forced to cancel the recording sessions. So he built “The Winners,” a giddy perseverance anthem whose verses all begin, “I was going to cancel …”

He has many fresh designs forthcoming, which is not a state of affairs to take for granted. Ten years ago, it was a given: Back then, he and Chad Hugo, the team called the Neptunes, were the most successful and prolific production auteurs during an era when being a production auteur seemed like pop’s highest calling. Any given hour of songs on pop, hip-hop, or R&B radio was practically guaranteed to feature multiple examples of their work: hits by Justin Timberlake, Usher, T.I., Britney Spears, or No Doubt; massive, grandparents-dance-to-them-at-weddings smashes like Nelly’s “Hot in Herre” and Snoop Dogg’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot”; somewhat more rarefied favorites like Clipse’s “Grindin’ ” and Kelis’s “Milkshake.” It is difficult to overstate just how much the sound of American popular music, post-millennium, had to do with their desiccated funk—crisp, minimal, and pointillistic, heavy on blipping synths and Williams’s clattering drums, often forgoing bass lines in favor of yawning empty spaces.

That sound inevitably lost some of its purchase on the charts, by which point the Neptunes were already diversifying into new enterprises anyway; by the turn of the decade, they were recording and touring with their live band, N*E*R*D, and Williams was working on projects like the soundtrack for the animated film Despicable Me (or, as of last year, helping score the Oscars broadcast). Lately, though, he’s back to accumulating high-profile solo production and songwriting credits, and some of the songs they’ve been attached to have strayed far from the frosty, snap-and-clack appeal of the old Neptunes sound: They’ve been, one notices, pretty lush. A song with Frank Ocean features twinkling keys and Stevie Wonder vibes (“Sweet Life”); a track with Kendrick Lamar is woozy and bass-driven (“Good Kid”); the reunion single he worked on for Destiny’s Child sparkles calmly along (“Nuclear”). He made a drizzly sigh of a song with the Malaysian singer Yuna (“Live Your Life”), a track for Rick Ross that’s largely a tumble of vocal-jazz harmonies (“Presidential”), and a goopy disco cut with the band Scissor Sisters (“Inevitable”). The word Williams uses for this development is color. “I’m always trying to make what I feel is missing,” he says, “and there was a lot of minimal stuff for so long. It was like: Boom. Pssh. And I could just”—he makes that snare sound again, this time miming a gun to the head. “It was just too much. So I needed color. Everybody else was like steely, minimal. I was like color, rainbow, many different versions of the rainbow. Rainbow, but with tertiary colors. Rainbow, gingham print.”

The apotheosis of gingham-rainbow Williams might be that soundtrack for Despicable Me, for which he wrote and performed a few cuts of childlike sunshine pop; the music he’s made for the upcoming sequel is heavy on sprightly Motown sounds and psychedelic vocal harmonies. “I’m just in that place,” he says, “because I feel like everything is so, ‘I’m super-mad! Cocaine! I’ll shoot you! These chicks is on drugs!’ And I just feel like there’s so much more to life, you know? I grew up in an era when people would talk about everything, and even Kermit the Frog had a hit. Random shit, like, ‘She’s got Bette Davis eyes’—and that was a hit!” As he’s playing songs, he pegs the era he’s reminiscing about as stretching between 1976 and 1983, when he turned 10; he talks about “reefer music,” the kinds of luxurious songs he associates with people passing around joints; at one point, he decides he needs to find DVDs of the old show Solid Gold.

He’s not the only one harboring such impulses—more than a few of the past decade’s pop and R&B mainstays seem to be gravitating toward the silky, “mature,” and nostalgic, with big ambitions for both the harmonies and the sentiments. To hear Williams tell it, though, the crux of his production work isn’t about being in touch with the right sounds; it’s his role as a stylist, a student of character, and a professional enthusiast of other people’s spirits, someone who can pick out a vocalist’s essence and outfit it accordingly. He’s a comfortable presence (you can imagine him bonding with crusty rap goons and teenage pop stars alike), quick to notice details about others and let them know that he’s noticed. Within minutes of meeting me, he’s asked about my shoes, and employed my glasses in an extended metaphor about how style conveys spirit: “It’s the way of a person that’s their personality. It’s not that he’s a ‘happy’ person—there are a lot of happy people—but his way of being happy, his way of wearing a shirt, his way of speaking to her; that’s what makes her love him.”

Calling him a professional enthusiast is, for the record, no exaggeration: He’s chock-full of extravagant praise for those he likes. Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen (“I’d put The Nightfly in my top twenty”), rapper Q-Tip (“He just walks on air”), composer Hans Zimmer (“like a walking Da Vinci”), J. J. Abrams (“a genius”), his own employees. When he released a book last fall—Pharrell: Places and Spaces I’ve Been—it was about other people’s work, from Zimmer and Kanye West to Anna Wintour and Buzz Aldrin. (Williams is into space travel and science fiction but, amazingly, not the show you’d think: “I’m so terrible—I named my label, Star Trak, after Star Trek, and I don’t even know the black lady’s name.”) He keeps underlining what a privilege it is to be around such people, which seems at first like the kind of thing one repeats to stay humble—until he describes the time, in the late nineties, when he first presented tracks to Busta Rhymes for consideration, and you actually picture the ascent of the Neptunes, two junior-high friends from Virginia Beach, into the pop world. “All these people,” he says, “they were like deities. It was like being on Mount Olympus, where Apollo and all the gods were. Think about it: Busta’s voice is not ordinary. You don’t go to school with a guy like that, and you don’t know anybody’s dad that sounds like that. But here he is, in the full pigtail dreads. Chewing gum, reading a sports magazine, listening to these tracks, not even looking up one time, and I was so honored, because it was Busta.” (One of the beats Rhymes rejected became Kelis’s memorable debut single, “Caught Out There,” a sound it’s now hard to imagine belonging to anyone else.)

At the moment, though, his biggest raves are for French dance duo Daft Punk, whose much-acclaimed new album features Williams on two tracks, singing his own melodies and harmonies—one of them, “Get Lucky,” already looks like a contender for song-of-the-summer status. “I cannot believe that I was a decimal, a comma in that equation,” he says. “Forget it. ’Cause I’d be there just to hold up the equals sign, and I got to be a digit.” Working with Daft Punk sounds … rigorous. “Everything is concise, precise, gridded. There are no gray areas for them. They don’t understand settling. They believe in doing it 200 more times than the previous 200.”

You’d think do-it-400-times perfectionism would be something new for Williams, whose long discography attests to just how quickly he can turn out good songs—the picture many listeners had of the Neptunes’ workflow involved Williams jetting around capturing ideas, singing guest vocals, and appearing in videos, while Hugo, back home, did the painstaking techie work of finishing and polishing. Williams says he’s very particular, though; something like a less-than-perfect drum sound will nag at him. “It’s like if you’re late for work, and you throw on socks—they’re both Nike socks, but one has a gray toe. No one’s ever going to see it, because it’s in your shoe. But that fucks my whole day up.” The biggest gray toe of all turns out to be Williams’s own career as a vocalist, which started with choruses and hooks he recorded as placeholders and demonstrations, only to have artists—like Mystikal, on 2000’s “Shake Ya Ass”—figure they sounded good enough to leave as is; he can’t listen to some of them without being reminded of the great singer he’d planned to replace himself with.

In the case of one Despicable Me song, the preferred singer would have been Donald Fagen—a real deity when it comes to butter-smooth, jazz-inflected, harmony-rich studio-rattery. There’s still plenty of neck-snapping clatter in Williams’s latest batch of work, but we can probably, he says, expect more of that color and texture and harmony, whether it’s in maximalist Solid Gold electro-funk, sentimental disco, or gray-skied softness. (Or shiny international hit-making: Some of his more fascinating jobs lately have been for huge-scale pop and dance acts like Gloria Estefan, Adam Lambert, and British singer Mika.)

One can’t help noticing that Daft Punk, too, spend their new album stepping away from oversize arena-rocking and further into gooey soft rock and light-stepping disco. And the track on it that Pharrell gets especially gushy about—the one that’s “going to change your life; not your mind, your life”—is “Touch,” featuring vocals from Paul Williams, the seventies singer-songwriter whose best-known song is still “The Rainbow Connection,” Kermit the Frog’s big hit. It is, Pharrell says, “the best song I’ve heard in years. It’s magical and majestic at the same time. It is unbelievable. It made me emotional. I didn’t know that sounds could be put together that could do that to people.” He lifts up from his skaterish sprawl on a couch and leans in, shaking his head, another enthusiastic rave building up: “He’s one of the best writers—Paul Williams is one of the best writers ever.”

*This article originally appeared in the June 3, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.