Cinema is a medium. Television is an appliance. Cinema is art. TV is product. Cinema is driven by directors. Television is driven by writers and producers. That’s why there’s nothing good on TV.

If you’re a cinephile, there’s a good chance I had you up until that last sentence, a cocktail-party cliché so outdated that it might as well be wearing an ascot. But the lead-up to it has proved surprisingly resilient among cinephiles. Even now, in the era of think pieces calling The Wire the Great American Novel and insisting that television is somehow “better than” movies, the notion persists that TV is not a director’s medium—that any creativity comes from the writer or producer, whose jobs fuse in the P.T. Barnum–esque title “showrunner.”

But here’s the thing: It isn’t true and maybe never was.

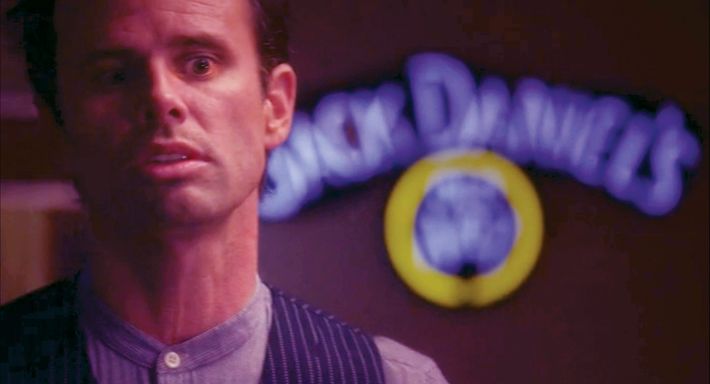

Consider a fleeting moment from season four of FX’s excellent Western-flavored crime thriller Justified: “Outlaws,” directed by John Dahl (film credits: The Last Seduction, Rounders). Backwoods gangster Boyd Crowder (Walton Goggins) sits at a table in his dive-bar headquarters, confronting local power brokers who think they own him (top).

“Now, I know people like you are used to taking from people like me,” Boyd drawls, the camera hanging back to show the configuration of his adversaries. “But there comes a point where people like me can’t take any more taking.” When Boyd stands up, asserting his power, the scene shifts into a close-up, showcasing his determined face.

“Now, all the things you’ve done, the way you’ve built your fortunes, it may make you criminals,” he says. “But it does not make you outlaws.” The scene snakes onward, ratcheting up tension by cutting between wide shots of the room and close-ups of Boyd and his would-be masters. The crowning shot shows Boyd from the back, center-frame, flanked by the old rich guys. His cocked pelvis and akimbo arms evoke the iconic pose of the gunfighter, but there are no holsters on Boyd’s hips. His confidence comes from his willingness to delegate (his cousin is behind him, covering the old guys with a revolver) and his theatrical mastery of word and gesture. The power brokers’ eye lines aren’t looking up at Boyd’s face, but farther south—a hilariously correct visual joke, considering that the scene is about cojones.

Boyd Crowder’s badass aria is a superb example of how to embed meaning in a moment without making a big deal of it—old-school classical direction, shot on the cheap with digital cameras. But it’s also an accidental metaphor for filmmaking in the early years of the 21st century. TV directors, the new outlaws, are weighed down by burdens that the old rich gangsters haven’t dealt with in ages, but they’re holding their own, and they’re full of surprises.

Thirty-two years after Hill Street Blues, 29 years after Miami Vice, 23 years after Twin Peaks, and fourteen years after The Sopranos, consensus persists that TV is not a director’s medium. There’s a certain truth to that charge, but it’s not as encompassing as you think. It’s true that TV is driven by long-form storytelling, and a related obsession with continuity and consistency. Showrunners drive and manage the medium, and if you’ve spent time on film sets, you understand why. Directors tend to think in terms of images and moments; those skill sets aren’t often compatible with the left-brain requirements of managing a sitcom or drama (though there are always exceptions; see veteran TV director Paris Barclay’s executive-producer credit on FX’s stylishly nasty biker drama, Sons of Anarchy). It’s also true that, for consistency’s sake, the showrunners get together with a pilot’s cinematographer, art director, costumer, and other collaborators to decide on the look and feel of a show before the pilot’s cameras roll, and any director who comes in afterward has to work within that preexisting vision.

But if TV is still a factory, it’s hardly stamping out interchangeable widgets. It offers an increasingly diverse array of storytelling modes: hypnotic minimalist nightmare (Top of the Lake, The Killing); stately, classical A-picture (Mad Men, Game of Thrones, Boardwalk Empire); gritty, run-and-gun B-picture (Sons of Anarchy, Justified, The Walking Dead); traditional three-camera sitcom (How I Met Your Mother, Anger Management); laugh-track-free pseudo-documentary (Parks and Recreation, Modern Family); glossy quasi-theatrical rom-com (The Mindy Project); trash-expressionist midnight movie (American Horror Story, Banshee); graphic novel (Archer, Bob’s Burgers); and droll-gritty indie (Girls, Louie). A director who jumped between three or four of these programs could serve the material, as they say, and still create one hell of a reel.

Plus there are always constraints on filmmakers, be they budgetary or stylistic. Prewar movie studios and low-budget impresarios like Roger Corman were equally likely to assign directors to projects whose casts and crews were locked and wish them well: Do the best you can, kid. You’ve got a million dollars and four weeks. Sometimes there was even a house style that directors had to honor. Cinephiles can tell an old MGM Studios picture from a Warner Bros. picture from twenty paces away with the sound off, or a Jerry Bruckheimer–produced action flick, for that matter. Networks have house styles, too. Visually oriented TV buffs can distinguish an HBO drama from an FX drama from an NBC drama after a minute or two, by studying the cutting, camerawork, and music. The constraints of TV production don’t stop great direction from happening, any more than they stopped it from happening on movie sets in the decades before the Cahiers du Cinéma gang decided that the director was the primary author of a film.

Martin Scorsese—the executive producer of Boardwalk Empire as well as the director of many a great movie—famously said that “cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” TV direction? Same thing. We remember great TV moments because of the sum total of their creative choices, gathered under the descriptive umbrella of “direction.” Think of the closing montage in the third episode of The Americans, set to Roxy Music’s “Sunset,” climaxing with FBI agent Stan Beeman (Noah Emmerich) discovering an overdose that he knows is no overdose; that extraordinary episode was directed by Thomas Schlamme, whose roving camera enlivened Sports Night and The West Wing.

Heathers director Michael Lehmann helmed the American Horror Story episode “The Name Game,” which included the perverse spectacle of Jessica Lange’s hallucinating nun leading fellow inmates in a line dance to the title track; it played like a very special episode of Glee set in hell.

The horrifying massacre that ended season three of Boardwalk Empire, with disfigured sharpshooter Richard Harrow mowing down an army of gangsters, is the handiwork of Sopranos veteran Tim van Patten, the Sam Peckinpah of pay-cable mayhem.

The Breaking Bad episode “Madrigal,” which contained not a single dull shot and built to an agonizingly tense hostage scene in a house, was directed by Michelle MacLaren, whose sense of space, light, and pacing recalls Alan J. Pakula (Klute, All the President’s Men).

TV didn’t just wake up one day and let directors direct. There’s a long history of great filmmaking on the small screen, stretching from the fifties to the present. In The Moviegoer, Walker Percy wrote of recalling movie moments more vividly than moments from his own life, such as “the time John Wayne killed three men with a carbine as he was falling to the dusty street in Stagecoach, and the time the kitten found Orson Welles in the doorway in The Third Man.” You could build a Percy-style list of great television moments: the time Archie Bunker told Meathead that he knew his father loved him because he beat the hell out of him, the camera creeping closer to the bigot’s faraway eyes; the time Burgess Meredith’s librarian accidentally dropped his glasses in The Twilight Zone’s “Time Enough at Last” and we got a point-of-view shot of a world permanently out of focus; the time Miami Vice detective Sonny Crockett paused en route to a confrontation with a drug dealer to call his wife from a phone booth, the car and phone booth perfectly balanced in a wide shot with a neon sign buzzing in the background; the time ER nurse Jeanie Boulet sang Green Day’s “Good Riddance (The Time of Your Life)” at Scott Anspaugh’s funeral; the time Homeland’s Carrie Mathison walked slowly around the interrogation room, turning off all the cameras, then told her prisoner and ex-lover Nick Brody, “Alone at last”; the time Mad Men’s Peggy left the agency to start a new life while the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” blasted on the soundtrack like an anthem. These and other indelible moments didn’t just magically appear on our screens. They were directed.

Why, then, does the public tend not to notice the names of TV directors—not even the ones who directed the scenes and episodes cited in the paragraph above? (They are, in order of mention, Paul Bogart, John Brahm, Michael Schultz, Charles Haid, Lesli Linka Glatter, and Phil Abraham.) If you watch TV with open eyes and ears, you can recognize that these people are artists, just as Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola were artists when they worked for Corman, and just as Victor Fleming was an artist when he directed chunks of Gone With the Wind for producer David O. Selznick, arguably the most hands-on producer in film history. Where’s their MoMA retrospective? Why is there no auteur theory of TV?

One explanation is that movies have a half-century head start on TV, so there’s been more time for critics to settle on terms and definitions. I like to tell people that TV, as both business and art, is at roughly the same place in its development as cinema was in the late fifties, around the time that the French floated the auteur theory. We’re still figuring out who the “author” is on TV shows. We’re still taking into account whether we’re talking about the show as a whole or a particular episode, and why. We rarely think of TV as being directed, unless the show’s main creative force has already been identified as a theatrical director (as David Lynch was before Twin Peaks) or doubles as the show’s star (like Louis C.K. or Lena Dunham). It’s not wrong to attribute a program’s personality to showrunners—the Matt Weiners (Mad Men) and Vince Gilligans (Breaking Bad) and Shonda Rhimeses (Scandal)—but it doesn’t tell the whole critical story. Showrunners aren’t on the set every single minute, and within the showrunner’s big picture are a series of smaller pictures: the scenes, the moments, the shots. It’s on these smaller canvases that episodic directors work their magic.

Television’s creative constraints have loosened in recent decades, but we should not forget that the medium produced art before David Simon was a glint in his mama’s eye. Even in the supposed pre-style era there was visionary filmmaking on television: the Kabuki-like sitcom minimalism of The Honeymooners; Ernie Kovacs’s experimental, highly visual slapstick; the atmospheric morality plays of The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits; the Pop Art eye candy of The Prisoner and the original Star Trek; and the horror-comedy stylings of The X-Files, which once staged a whole episode (series creator Chris Carter’s “Triangle”) in a handful of elaborate Steadicam shots. John Frankenheimer’s direction of live theater for Playhouse 90 and other anthology shows boasted imaginative touches that would have earned a slow clap from Rushmore’s Max Fischer: realistic fake animals, miniature sci-fi panoramas and military vehicles, even a flood re-created in a water tank. Amazing direction happened on TV all the time before cable, but almost nobody recognized it as such because we were told that art was as anomalous in television as wildflowers in a toxic-waste dump, so there was no point keeping an eye out for it.

But our eyes, ears, and hearts told a different story. If television were truly disposable, our memories wouldn’t replay certain moments as if they happened to us: the wide shot of Tony Soprano, high on peyote, standing on a desert cliff and screaming, “I get it!”

The way the camera pushed in on the aged and dying faces of Six Feet Under’s main cast as the show’s final episode raced toward oblivion.

The slow pan across the faces of Springfield townspeople gathered in Ned Flanders’s fallout shelter, singing “Que sera sera.” Those episodes were directed by Alan Taylor, Alan Ball, and Bob Andersen. Like so many other great TV directors, they were authors of the moment.

*This article originally appeared in the May 20, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.