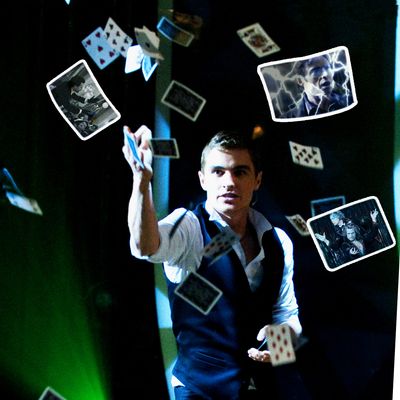

If there’s a trick the cinema has rarely, if ever, pulled off, it’s making a decent movie about magicians. The latest attempt is Now You See Me, this weekend’s star-studded crime caper about a crew of expert illusionists (including Jesse Eisenberg, Woody Harrelson, and Isla Fisher) who use their skills to pull off daring heists and then redistribute their bounties to the needy. The film futilely attempts to conjure amazement from a laughably intricate story that pivots around David Copperfield–esque exploits like teleporting a spectator from Las Vegas to a French bank vault, and reallocating a benefactor’s riches to audience members mid-show. That Copperfield himself was a consultant on the project is apt, because like Copperfield’s own rash of flashy eighties TV specials — in which, among many other wannabe-extraordinary ruses, he made the Statue of Liberty disappear, escaped from Alcatraz, and walked through the Great Wall of China — the film is all glitter, flash, and overwrought showmanship in service of tricks that, onscreen, fall far short of astonishing.

The fundamental problem is one of detachment from the ruses at hand. In person, the best magicians astound by seemingly defying natural law in plain sight. Cinema, on the other hand, operates on a separate plane of reality from its audience, and thus a magician pulling a rabbit out of his hat onscreen is a deed no more amazing — and, in fact, virtually identical in terms of wonder felt — to the super-powered fisticuffs and fantastical car explosions of your average summer action extravaganza. Especially in an era of endless computer-generated wizardry, a film magician’s talents are rendered distinctly unamazing by the fact that they’re accomplished not through hands-on cunning but, instead, via cinematic tricks. Hence, in films as varied as Ingmar Bergman’s 1958 The Magician and Christopher Nolan’s 2006 The Prestige, magician protagonists fail to stun and startle with their feats because, in reality, they’re not performing them; it’s all the careful byproduct of multiple takes and careful edits, which negate any potential excitement elicited from seeing something that should not, or could not, exist.

It’s an odd fact, as rarely has a subject seemed at once as perfect for, and thoroughly incompatible with, film than magicians, whose sleights of hand are a natural counterpart to the cinema’s staged fantasies. That seminal film directors like George Méliès (think of all the magic in Hugo) were themselves illusionists certainly helped cement, from the outset, the two arts’ inherent bond. Alas, the link has, over the years, proven more superficial than sturdy. True magician’s games only thrill when there’s no way one can discern, while in their presence, how they’ve been accomplished. In a film, that’s just not the case. To be sure, the occasional film captures some of the uniquely enchanting power of illusionists — Werner Herzog’s 2001 Invincible, or the 1978 Anthony Hopkins ventriloquist-dummy thriller Magic, are the rare exceptions. But too frequently, such films, failing to educe anything like a legitimate “ooh” or “ahh” from their hoaxes, simply attempt to legitimize themselves through the time-honored device of making their stories about how the movies are themselves enthralling fantasies. That theme is true, of course. And yet it mistakes all illusions as somehow equal, when in truth there’s something far more magical about the fact that, say, Edward Norton chose to boast a ridiculous goatee in The Illusionist than anything actually performed by his titular character.

Left incapable of concocting breathtaking illusions that read true, many films strive to mesmerize through narrative misdirection, as proven most recently by the twisty pretzel plotting of The Prestige and Now You See Me. In these cases, however, the stories are so blatantly upfront about the fact that all forthcoming action is an illusion that it’s impossible to take any aspect of their tales as legitimate — or, consequently, be surprised by their subsequent, expected rug-pulling revelations. The most successful practitioner of this cinematic game, in fact, comes not from a movie about magic at all, but one about criminal deception: House of Games. Taking a cue from participating Mamet regular (and legendary stage magician) Ricky Jay, David Mamet’s 1987 debut is an expert cat-and-mouse battle of wits between Joe Mantegna’s gangster and Lindsay Crouse’s psychiatrist that thrives courtesy of screenwriting and directorial ingenuity, exhibiting a subtle wiliness that is largely absent in movies about magic and vital to any real narrative con.

In general, however, the primary shortcoming with movies about magic is that they are almost always either obvious or inapt — the former (like 1947’s classic noir Nightmare Alley) in that they tell us something we already know (magic isn’t real! It’s a carefully orchestrated trick!), and the latter (like the middling 2008 John Malkovich vehicle The Great Buck Howard, or Clive Barker’s 1995 horror show Lord of Illusions) in that they suggest something we know is a lie (magic really is real!). In both instances, there’s no wonder, no excitement; all they can hope for is shrugged-shoulder acknowledgement of the execution. Just because something is impressive or confusing does not make it magical. In that respect, then, perhaps this past March’s star-studded flop The Incredible Burt Wonderstone was an ideal film about magicians — treating them not as purveyors of awe-inspiring marvels, but as two-bit charlatans whose tricks are just too much hocus pocus.