A quarter of a century ago this week, John McTiernan’s action masterpiece Die Hard was released into theaters, and it’s not an understatement to say that we’re still reeling from the impact. The film turned one Bruce Willis — until then thought of primarily as a comic actor and harmonica player — into a Hollywood action star, a position he’s still convincingly holding down 25 years later. It also unleashed armies of imitators: There was Die Hard on a Ship (a.k.a. Under Siege), Die Hard on a Mountain (a.k.a. Cliffhanger), Die Hard at the Stanley Cup Finals (a.k.a. Sudden Death), and so on, all the way up to this year’s double dose of Die Hard at the White House movies (a.k.a. Olympus Has Fallen and White House Down), not to mention Die Hard Beating a Dead Horse (a.k.a. A Good Day to Die Hard, a.k.a. Die Hard 5). It is, in fact, partly thanks to these imitators (as well as the Willis franchise’s lesser sequels) that we often forget how expertly made the original Die Hard is: It’s as much a perfectly calibrated character piece as it is a kick-ass action flick.

So what has the action landscape looked like since that fateful day in 1988 when we first met John McClane en route to Nakatomi Plaza? For the past few months, I’ve been watching and/or rewatching almost every major action movie made since then in an attempt to come up with the best ones. The good news is that a lot of awesome action movies have been made over the past 25 years. The bad news? Not all of your favorites will be on this list.

First, some ground rules:

- Not every movie with action in it is an action movie. Believe it or not, it is sometimes very hard to determine just what constitutes an action movie. For the purposes of this list, we decided that an action movie not only had to have a lot of action scenes in it (duh), but that it had to be a film that wouldn’t make any sense if you took all the action scenes out of it — that is to say, the action had to be a key way of moving the plot forward. As a result, we filtered out a lot of great films, masterpieces even, that didn’t quite qualify as true action movies: Michael Mann’s Heat, for example, or Tony Scott’s True Romance, or the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy.

- Only one film per franchise. This is a cheat, sure, because not all franchises are created equal: There’s only one great Matrix movie, but several great Once Upon a Time in China installments. But still, in an effort to keep this list from becoming overwhelmed by certain films and directors, we decided to limit it to one title per franchise.

- No animation. Because it just wouldn’t be fair to the other movies if we suddenly allowed Pixar and Miyazaki in there.

Anyway, here they are: the 25 greatest action movies made since Die Hard.

The peculiar, profane thrill of watching a Jackie Chan film is the feeling that at any given moment, you may be about to watch someone — usually Chan himself — actually die in real life. This, despite the fact that the films are often candy-colored comedies without a truly serious bone in their bodies. (They’re rendered even more goofy when dubbed into English, as this film and several others were when released Stateside.) Chan the star/impresario, working here with one of his better directors, Stanley Tong, understands what makes a stunt truly awe-inspiring: While your average action film might show someone falling from an alarming height and then cut to a shot of their hard landing, Chan and Tong often make sure this happens in the same shot. And they find just the right camera angle and distance that will allow you to see that, yes, it is in fact a movie star riding that motorcycle as it leaps onto a train, or hanging from that helicopter as it zooms over Kuala Lumpur, or jumping onto that speeding car in the middle of traffic. Piece by piece, they pick away at your disbelief, until you’re sitting there, curled up in a fetal position, afraid to look yet unable to turn away. This is why Jackie Chan matters. And why, when it comes to breathtaking stunts, nobody has yet topped him.

Full disclosure: Not all of us thought this movie was such hot shit when it first came out. Neither Patrick Swayze’s philosophy-spouting surfer/bank robber nor Keanu Reeves’s slightly too earnest undercover Fed seemed particularly convincing at the time. And at the time, director Kathryn Bigelow’s famously over-the-top shooting style, full of long-lenses and whip pans and breathless exposition scenes, was something of a joke, too. But watch it again and behold its greatness. Reeves, who up until then was known for coming off as either too much of a surfer boy or too much of a square, now seems perfectly cast as both: Who else could play a straight-arrow cop posing as a surfer? And the late Swayze, who used to be a running joke as an actor, now seems touchingly earnest —an endearing criminal with his own kind of twisted code. Sure, maybe Point Break is stupid, but it’s a glorious — and gloriously innocent — kind of stupidity that you wish modern action indulged in more often.

The idea of the antihero is nothing new, but ADHD action auteurs Neveldine/Taylor’s Crank takes it to a whole new level. Like many other movies of its kind, it’s essentially a wish-fulfillment fantasy, only this time the fantasy isn’t in the action itself. Rather, Crank is a fantasy about how much of a jerk Jason Statham’s Chev Chelios gets to be, given his circumstances — he’s been loaded with a poison that will stop his heart, and he has to keep his adrenaline going if he is to survive. So, this is a guy who gets to do anything, turning the backstreets and dank lairs of urban Los Angeles into a landscape of pure, wicked impulse: He throws around racial epithets in order to get beaten up, he breaks into hospitals and takes medicine from sick people, he does his girlfriend on a crowded Chinatown street, and much, much more. In concept, this is Speed, but with a person. In execution, it’s a video game about being an asshole.

Make all the jokes you want about glowing purple mushrooms and winged hammerhead rhino dragons, but this one’s a keeper, in part because of creator James Cameron’s compellingly schizoid personality — he’s part hippy-dippy earth-child, part alpha-male military fetishist. With Avatar, he laid his soul bare, creating a tree-hugging enviro-action epic that also speaks fluent badass. So spectacular and strange you have to remind yourself to pop your eyeballs back in their sockets when the end credits finally start rolling, the film is at once deliriously new and deeply elemental. The plot isn’t all that different from any number of outsider-gone-native forebears, from A Man Called Horse to Dances With Wolves to the John Carter of Mars books. But Cameron also conjures up a distant world imagined down to its tiniest detail, and he has the cojones to stage feverishly intricate, surprisingly brutal action scenes. And he’s not afraid to turn the U.S. military (along with that macho-speak he knows so well) into the film’s fire-breathing bad guys. Is Avatar his greatest film? Absolutely not. (See further up the list for more.) But in many ways, it’s his most personal.

Photo: WETA/TM & ? 2009 Twentieth Century Fox - All Rights Reserved - Not for sale or duplication.

With this, the first of the Daniel Craig Bonds, the 007 series entered a new era — tougher, streamlined, and with just enough gravitas to keep up with the times. (Some have claimed that the last three Bonds have effectively Nolan-ized the franchise, but let’s not go crazy here.) From the amazing parkour chase — performed with un-Bond-like conviction — to the touching, tragic love story, Casino Royale is a full-blooded action film, the kind that envelops you and actually makes you fear for a once-indestructible hero. I mean, how many other action movies can boast a scene where the protagonist goes into cardiac arrest? (If you answered Crank, okay, fine, give yourself a cracker.)

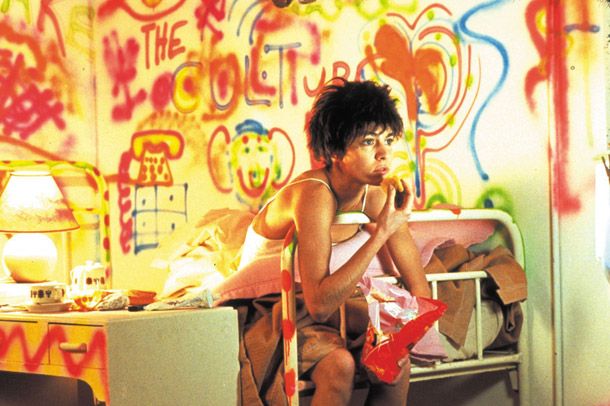

Luc Besson’s stylish thriller about a beautiful street punk recruited by a clandestine French service and trained to become a deadly assassin is, like several of the more iconic action movies on this list, all about transcending mundane reality: A tale of an ordinary, anonymous person discovering that they can do extraordinary things under the right circumstances. After all these years, it’s odd to see that it has relatively few actual action scenes. But the ones it does have unfold exquisitely. Besson consistently keeps us in the head of his lead character, who is blind to the grand scheme of what her paymasters are trying to accomplish. We discover the story through her, and we never quite know what’s going to happen next. That may not sound like a big deal, but it pays real dividends for the audience — every moment of this tight, tense little film feels like a twist of sorts.

Ironically, while the late Tony Scott was one of the most pivotal and influential action directors of the eighties, his best films from the nineties onward — True Romance and Crimson Tide — were not really action movies. Then, with what turned out to be his final work, Scott delivered one of his greatest, in this awesomely entertaining, heart-stopping, and even touching runaway train thriller. Denzel Washington and Chris Pine are the two pros — one a seasoned engineer, the other a rookie hothead conductor — who have to stop the hazardous material-loaded freight train before it goes off the rails and wastes a major population center. A film that perfectly blends the one-liner-friendly action that Scott once specialized in (“That’s a missile the size of the Chrysler Building!”) with a surprisingly poignant, class-conscious dynamic between its two heroes.

Photo: Robert Zuckerman/TM and ? 2010 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

Most of the movies on this list, even the ostensibly dark ones, are still variations on wish-fulfillment fantasies. Not here. Veteran Japanese director Kinji Fukasaku’s pitch-black look at a dystopian future where schoolchildren kill each other for sport until the sole survivor emerges victorious — with some similarities to The Hunger Games — is a nonstop horror show of kids killing each other, with onscreen text helpfully telling us how many are left. (And right in the middle of it all is the great Takeshi Kitano as the kids’ teacher, who gets to do such Kitano-esque things as suddenly stab at an unruly teenager.) This is not a world you’d ever want to live in; the film is borderline unwatchable. And you’ll want to take a long shower after realizing how exciting, how funny, and how generally brilliantly made it is.

It took ages for them to finally pull off a proper Spider-Man movie. (Along the way, such major talents as James Cameron made noble but abortive attempts.) Ironically, the easiest approach turned out to be the best. The first installment of Sam Raimi’s trilogy treated the story of how nerdy Peter Parker became the legendary web-slinging superhero with an easygoing, straightforward charm and loads of visual and verbal wit. But for the second film, Raimi took those basic blocks and built something bolder on top of them. First, he utilized state-of-the-art effects to create action scenes of startling fluidity; nearly ten years later, they’re still great, not just for their suspense but also for their visual beauty. Then, he lent the interpersonal back-and-forth of the film’s characters a weight you wouldn’t ordinarily expect. (Rarely has the melodrama of the comic-book page translated so well to the movie screen.) Spider-Man 2, it turns out, is a film about the bonds between men and women — from the yearning between Peter and Mary-Jane Watson (Kirsten Dunst), to Doctor Otto Octavius’s (Alfred Molina) meltdown in the wake of his wife’s accidental death, to Aunt May’s continuing desperation at the absence of Uncle Ben. Many consider this the best superhero movie of all time. It’s certainly close.

Photo: Photo by Melissa Moseley/Sony Pictures/Columbia Pictures’ Spider-Man?2

It’s turned out to be one of the most strangely accomplished franchises. (Save, oddly enough, for the second entry, which was the one directed by John Woo, the action visionary.) And the first one is still in many ways the best (though the fourth, Ghost Protocol, comes close). In the assured hands of screenwriter Robert Towne and director Brian De Palma, what was supposed to be a cash-cow melding of a Tom Cruise vehicle and a beloved TV show became something thrillingly personal and dark — a film that operates in an atmosphere of such paranoia and betrayal that nothing ever feels real, or genuine. Add to that some sharp dialogue and a couple of magnificent set pieces — including the much-imitated and -parodied, never-matched Langley break-in that occurs midway through the movie. It’s a scene that shows us just how powerful a cinematic tool total silence can be. And oddly enough, its tense rigor somehow justifies the explosive, splendid ridiculousness of the Chunnel chase at the end of the film.

Gosh, remember Speed? It’s got a great, elegantly simple concept: A bus has been rigged to explode if it goes under 50 mph. Director Jan De Bont and writer Graham Yost steadily up the ante at just the right pace: First, the driver gets shot and has to be replaced … then the highway suddenly ends …then they start leaking fuel, etc. Meanwhile, a great romance between the two impossibly beautiful leads unfolds: This is, of course, when most of us first fell in love with Sandra Bullock, and it’s also when we realized that Keanu Reeves could make a decent action hero. And of course, its climactic explosion (when the bus, which has enough C4 on it to “blow a hole in the world,” finally crashes into an airplane) is still one of the greatest of all time, and a good example of how breathtaking action spectacle could be before CGI made it all so commonplace.

Photo: ? Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

In the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films, Harrison Ford was the perfect all-American hero (even if one of those heroes lived in a galaxy far, far away). He had exceptional skills and an endless supply of wisecracks, but at heart he was still an ordinary guy, just a very confident one. So seeing him as the lead in director Andrew Davis’s movie variation on the classic TV show, playing a doctor who’s been wrongly convicted of killing his wife, can at first be a bit disconcerting. This is a man who’s fragile, terrified, out of his element. But Ford turns out to be ideal for the role, likable but just distant enough that we’re fascinated by him. This is important, because we also have to have some sympathy for the U.S. Marshal who’s in hot pursuit of the fugitive, played by Tommy Lee Jones. Indeed, the film’s oft-repeated dialogue exchange between the two men (“I didn’t kill my wife!” “I don’t care!”) becomes emblematic of the film’s no-nonsense attitude toward innocence or guilt. It’s a beautiful action epic that’s all about the chase.

This thing just doesn’t let up, does it? From its very first shots, the third installment in the Jason Bourne series (the first three constituted a nice little trilogy, which last year’s unnecessary Bourne Legacy kind of tampered with) is a virtuoso display in how to hook your audience and not let go until the very final frames. Director Paul Greengrass gives the movie the sweep of a Bond film (it hops from Europe, to Africa, to America) with the you-are-there, close-quarters immediacy of a documentary. Meanwhile, Matt Damon is an ideal hero, equal parts puppy dog, cypher, and killing machine. We can’t quite tell if the expression on his face is vacant or tortured, and neither can he; he’s only half-remembering who the hell he is. The film’s “shaky-cam” aesthetic has since become a punch line, but here it’s never confusing, and at times almost startlingly clear (never more so than in the film’s celebrated cell-phone chase scene at London’s crowded Waterloo Station). And amid the dizzying set pieces, there’s even some whirlwind visual poetry, too, as when a camera follows Bourne as he leaps out of one building and in through another’s window — a remarkable stunt, captured perfectly.

Once upon a time, before he became the master of four-quadrant bloat and lost all sense of comic timing, Michael Bay made this ridiculously fun and witty flick about untested FBI agent Nicolas Cage and dangerous, aging ex-con Sean Connery breaking into Alcatraz in an attempt to thwart a terrorist attempt. Besides being one of the most quotable action movies ever (“Losers always whine about doing their best. Winners go home and fuck the prom queen!”), it’s also a perfect rejoinder to the notion that Bay’s signature hyperstylized action sequences were in any way inferior. Given the right type of material, and talented actors who know how to ramp up the theatrics, throwing everything but the kitchen sink at the viewer actually can work. Unfortunately, this was the last time the Baymeister had a script and cast that could match his outsize ambitions.

“Is it an action movie?” Are you effing kidding me? Tom Tykwer’s ridiculously great debut featured Franka Potente as a red-headed young German woman who has to run (and run, and run) to first procure and then convey $100,000 Deutschemarks to her desperate boyfriend, in order to stop him from robbing a bank. And it’s relentless: “Tykwer throws every trick in the book at us, and then the book, and then himself,” said Roger Ebert at the time. But it’s more than just breathlessly propulsive. With its trifurcated, “what-if” resolutions, it’s also a beautiful, almost transcendent meditation on love, betrayal, sacrifice, and fate.

At the time, we thought of Jurassic Park as the state-of-the-artiest of state-of-the-art big studio films — big, sleek, ultramodern, not a piece out of place. (We all chuckled as Sir Richard Attenborough’s character repeated his very meta mantra, “We’ve spared no expense.”) The effects don’t look so special and new anymore (even Nickelodeon shows can do the CGI-dinosaurs-interacting-with-people now), but the film still retains its ability to thrill, surprise, even shock. It’s a roller-coaster ride, but a beautifully sadistic one. And like so many of Steven Spielberg’s action spectaculars, it’s a movie with an old soul — the monster movie to end all monster movies. (Only, of course, it led to more.)

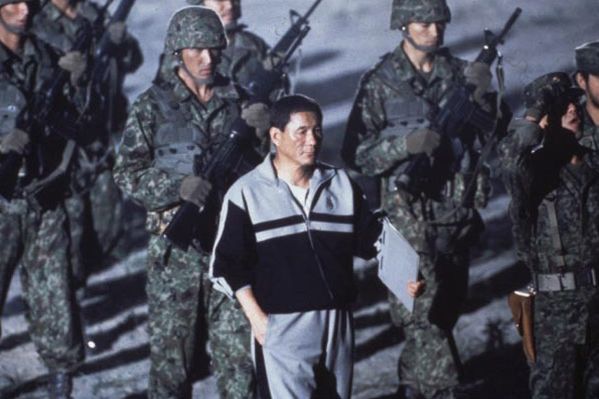

If the visionary Hong Kong cinema of John Woo was all about slowing action down so that it acquired the rhythm of dance, then Tsui Hark’s equally visionary Hong Kong cinema was all about speed. And his greatest weapon was Jet Li. In the first entry in this storied series (Tsui produced or directed six Once Upon a Time in China films, four with Li — they’re all varying degrees of great), the star leaps, kicks, and punches with such amazing agility and quickness that you can’t quite believe your eyes. (None of it’s CGI, in case you’re wondering. That came later, and, sadly, some of Tsui’s later films suffer from its overuse.) Into this epic, Tsui packs observations on honor, the encroaching technology of warfare, the struggle between tradition and modernity, the foreign economic invasion of China, and even the conflict between local militias and centralized power. For most of the first half of the film, Jet Li’s character desperately tries to keep the peace, kicking ass in an attempt to keep everyone else from kicking each other’s asses. Add to that numerous celebrated setpieces — the great “ladder fight” is still one of the best martial arts scenes you’ll ever see — and you’ve got a gorgeous, innovative action film.

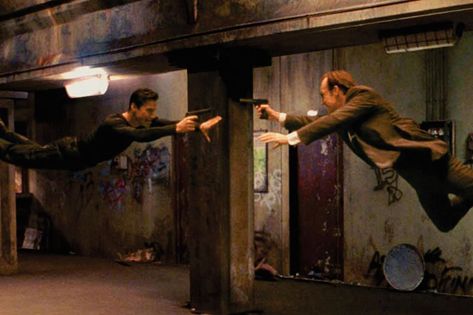

How odd that a film that’s all about shedding the scales from your eyes and seeing the world for what it really is, is itself so deeply in love with the virtual world it’s created. Because The Matrix isn’t about seeing what’s real and true, it’s about living in a (make-believe) world where a poor schlub (who, admittedly, looks like Keanu Reeves) can turn out to be a mystical savior figure, learn kung-fu with a simple download, have any weapon he wants in an instant, and even fly a helicopter with a simple command. Yes, the effects were revolutionary (though, years later, it’s hard to tell if “bullet-time” was a wondrous stylistic innovation or a curse that destroyed action movies forever), but without that quality of dream-logic that the film pretends to condemn while indulging in mercilessly, none of it would have mattered. In other words, The Matrix is the Matrix. And as far as we’re concerned, the sequels didn’t happen.

Jet Li keeps saying he’s retiring. The time to do so would have been after making this exquisite Russian nesting doll/hedge maze of an epic, a confounding stylistic, moral, and political puzzle. Li plays a fighter sent to dispatch an Emperor who is ruthlessly consolidating China under his rule. But the film plays out like a strange fable — a conversation between the reflective, paranoid monarch and his would-be killer, projecting a variety of scenarios that could explain the assassin’s presence in the royal chamber. Working with the biggest budget and scale of his career, director Zhang Yimou, who up until this point was known mainly for social and historical dramas that often ran afoul of government censors, takes the tantalizing concept and turns it into something exciting and mysterious. Some see it as an apologia for fascism, some see it as a meditation on the individual’s tenuous relationship with an all-powerful state, some see it as Zhang’s own take on the role of the artist in society. But pretty much everyone agrees that it’s gorgeous and breathtakingly choreographed.

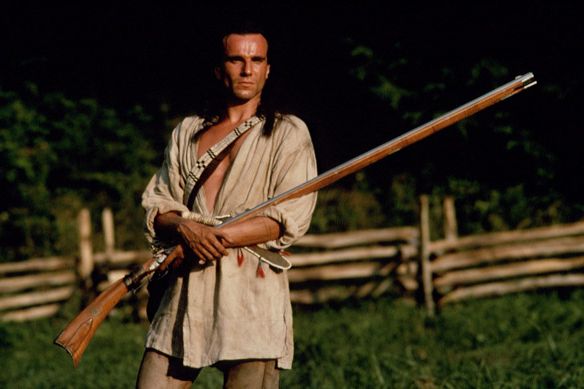

Daniel Day-Lewis brought what has by now become his legendary dedication to preparation to this Michael Mann adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s classic adventure novel — actually, it was more an adaptation of the 1936 film version — and the result was stunning. The action scenes often hold on Day-Lewis for uncommon lengths of time, and he moves with a remarkable combination of physicality and grace. Also, he and Madeline Stowe make one of the great movie couples, their animal attraction helping fuel the film’s melodramatic plotline. It’s not just one of the greatest of action movies, but also one of the greatest movie romances. Plus, the last twenty minutes or so — a sustained, nearly wordless footchase and face-off that’s drenched in pain, regret, love, sacrifice, and ethereal beauty — should be shown in every film school on a continuous loop until the end of time.

Photo: ? Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

The stripped-down, nocturnal L.A. of James Cameron’s groundbreaking 1984 action thriller The Terminator was in keeping with that tight, dark film’s mood of apocalyptic despair. By contrast, Judgment Day is epic, expansive, bright — and the destruction is on an entirely grander scale. The effects, of course, are legendary: The T-1000, which can become metallic goo at the drop of a hat and transform into pretty much anything it wants, is still one of the most impressive and scary villains ever. It was revolutionary CGI, but so many of the effects here are not CGI: Those are real trucks flying off those bridges for that chase scene. But maybe the best action scene in this film is the simplest: Early on, the two Terminators meet in a shopping mall and proceed to kick the crap out of each other, reducing the walls around them to rubble. (Think-piece idea: Consider America’s vision of its role in the world through the prism of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character from the Terminator films — from indestructible, all-powerful killing machine, to somewhat touchy-feely good guy battling even worse killing machines, to helpless bystander to Armageddon.)

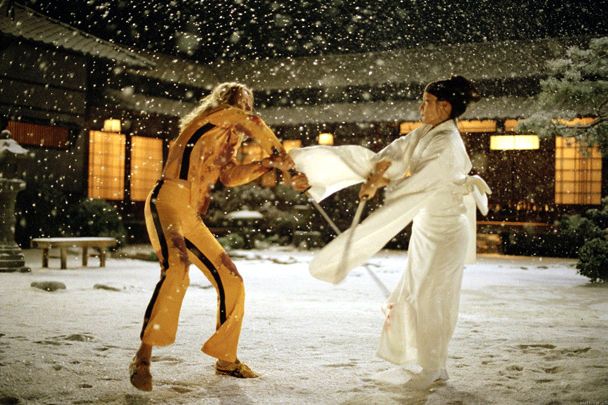

How crazy is it that at the time this film was released, the big question on everyone’s mind was, “Can Quentin Tarantino direct an action sequence?” Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs had plenty of violence and suspense, and Jackie Brown was tense and absorbing, but none of them could be called action-packed. So this first installment of QT’s magnum opus (originally intended as one movie, but released as two) was a real shocker — a master class in fight choreography and myth-inflected bloodshed, with action scenes of such clear-eyed intensity that you’d swear the guy had been making these films his whole life. As the Bride, the avenging mother, widow, and killing machine at the heart of the narrative, Uma Thurman has never been better; but then again neither has Lucy Liu, playing this first installment’s charismatic villainess, O-ren Ishii, with her own powerful backstory. And the film’s climactic House of Blue Leaves sequence, with the Bride battling a small army of sword-wielding assassins called the Crazy 88s, certainly ranks among one of the most epic fight scenes of all time.

Steven Spielberg spent the first part of his career making films about children, or about men who acted like children. So much so that “Spielbergian” began to refer to movies that trafficked in the wonder of childhood, with scenes of awestruck faces looking up at the skies and whatnot. But sometime in the nineties, all that changed for the man who had already done so much to define the parameters of the action-movie landscape for a generation. Now Spielberg started to make films about fathers — movies about men who learned the importance of parenthood (Hook, Jurassic Park, and later War of the Worlds) or who built surrogate families for themselves (Schindler’s List). Even a historical drama like Saving Private Ryan is a very personal film about a symbolic kind of parenthood — a nation seeking to save the last remaining child of a family that’s already been devastated; A.I., while it’s ostensibly about a young robot boy, is shot through with a parent’s sense of wonder, tenderness, and despair.

And then, in 2002, Spielberg gave us Minority Report. (It was a banner year for him, by the way, as it was also the year he released Catch Me If You Can, perhaps his most poignant statement on family yet.) Despite being based on a paranoid, dystopian story by Philip K. Dick, this is a film propelled by the parental instinct — from the haunted Tom Cruise character’s memories of his long-lost son, to the unsolved murder at the film’s heart. But Spielberg’s vision of family is more complex this time around. Consider the corrosive paternalism of the society that it depicts. A society that constantly seeks to give you what it thinks you want. A society that tries to predict crime before it happens and puts the future perpetrators in jail before they commit anything. In other words, a society afraid of letting go. This isn’t just a movie made by a father. This is a movie made by a father whose kids are growing up, and who uses his cinematic canvas to explore his complex feelings about it.

Oh, and it’s a great action movie, with magnificent setpieces. The jet-pack fight is harrowing and hilarious. The car factory chase is not only intense, but ends on a great nod to a scene Alfred Hitchcock always wanted to shoot. The spider-drone sequence is heart-stopping and grotesque. The shopping mall pursuit, where Cruise’s character and the pre-cog Agatha (Samantha Morton) evade their pursuers thanks to her ability to see the future, is not only brilliant, but probably also directly influenced the infamous Waterloo Station scene in The Bourne Ultimatum. But what makes Minority Report so special, so powerful, so epochal is the anxious heart that beats within it. It’s a movie about trying to protect your children, and dealing with your inevitable failure to do so.

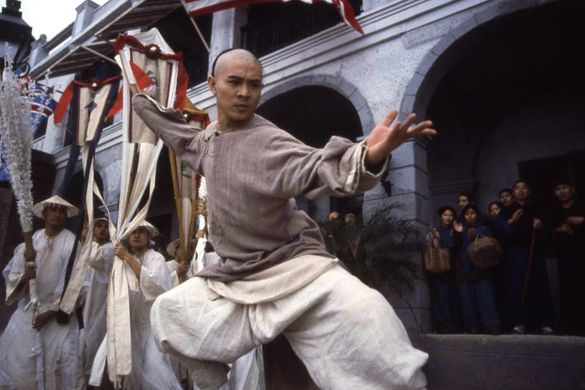

Every real film nerd from the nineties will have his or her own favorite, but let’s face it, this was the pinnacle of the “Heroic Bloodshed” genre of action that John Woo perfected in Hong Kong. The director had always had a Chosen One quality to him: He wed the classic tough-guy ethos of Jean-Pierre Melville with the sensuousness of Sam Peckinpah. He mixed the experimentation of Scorsese with the no-nonsense action efficiency of John McTiernan. But he wasn’t just a homage artist. He took all these influences and produced something very much his own. Hard-Boiled, in all its pre-CGI glory, still features some of the greatest action movie set pieces of all time, not to mention some insane motorcycle stunts that Woo could never get away with here in the safety-conscious U.S. of A.

Meanwhile, the film’s tale of conflicting loyalties on opposite sides of the law has been imitated many times, but never really matched. That’s because Woo, at heart, is a romantic. Hard-Boiled may be a tough, kick-ass action movie, but it’s also shot through with florid bursts of emotion, which successfully raise the stakes throughout. If we’re riveted to our seats, it’s not just because the fights and shoot-outs and explosions are staged to perfection, but because we really care for these characters.

But let’s not kid ourselves: Woo couldn’t have done any of this without Chow Yun-fat. Here was an actor who mixed and matched the same way his director did. Just as Woo used the aforementioned influences to feed his own vision, so too did his actor and alter ego perfect the ethos of a tough guy who is both a wiseass and a pro, both alone and deeply passionate. A sharp-shooting acrobat who can fly through the air with two guns in his hand, and an Everyman with a penchant for physical comedy. He’s Bruce Willis, Alain Delon, Harrison Ford, and Jack Lemmon all rolled into one. And here, he’s in full-on gun-fu badass mode, matched with Tony Leung at his mopey best.

Not everybody’s a fan of Christopher Nolan’s Batman films. (Our own David Edelstein, for starters,

vehemently begs to differ.) But here’s what cannot be denied: Nolan’s film and the trilogy it represents take the superhero genre — certainly the aughts’ most prevalent iteration of the action movie — and treat it as something worthy of novelistic ambition, an epic psychodrama that burns with contemporary relevance. As such, it’s an accomplishment for the ages.

Superheroes are often matched to society’s own psychological demons. In The Dark Knight, Bruce Wayne/Batman (Christian Bale), who was always uncertain about his role as a nocturnal masked vigilante, has to contend with the twin poles of his influence. On the one hand, he’s inspired delusional average Joes to don cheap Batman costumes and attempt to stop baddies, thus contributing to Gotham’s lawlessness; on the other hand, he’s inspired heroic District Attorney Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), who admires Batman’s sense of purpose and take-no-prisoners attitude. (The contrast is explicit in the film: The workaday vigilantes dress up as Batman but are clearly not our hero, while some look on Dent and imagine that he might be the masked crusader.) For Bruce, Dent represents both justification and liberation — the sense that what he’s done has not been for naught, and the promise that he can maybe give it all up soon.

And then comes the Joker (Heath Ledger), a guilt-free anarchist who represents another duality. He’s the flipside of the superhero, his high-pitched whine, colorful outfits, and loose-limbed gestures a stark contrast to Batman’s raspy growl, dark vestments, and lumbering, pained movements. And unlike Batman, the Joker likes inspiring fellow lunatics; as the film makes clear, his main weapon is his ability to make others do things for him. All of Nolan’s Batman villains in the trilogy share this defining trait — they want to make Gotham’s people destroy themselves. Thus, they force the vigilante into the one position a vigilante can’t handle: that of having to rely on others.

Nolan watches these opposing forces play out as a God might, his camera trained down among Gotham’s canyons of skyscrapers, often picking out individual figures or vehicles — a sharp visual corollary for a film that is, in effect, all about the individual’s responsibility to society at large. When Batman’s final, outrageous betrayal comes — when he turns all of Gotham’s cell phones and mobile devices into a citywide sonar to help him find the Joker — it seems at first as if Nolan is in effect attempting to make a case for the surveillance state that has emerged in the U.S. post-9/11. But look more closely and you see that this is the hero’s final damnation. The Joker has been trying to force Batman to debase himself, to betray the things he stands for. And finally, he does.

When it comes to action, Nolan, not unlike Woo, is more a Peckinpah than a Spielberg: He never does slow motion, but his action scenes are less about clarity and space than they are about movement, and rhythm. The truck chase in The Dark Knight is spectacular, breathtaking — even if we don’t always know what’s going on. Similarly, Batman’s climactic high-speed invasion of a building where the Joker is hiding out will drive you nuts if you try to follow the specifics of the action, as Batman takes out decoys and bad guys alike with warp-speed efficiency. But open yourself up to its rhythms and it becomes almost magnificently abstract. Despite many imitators and influences, the movie world has never seen anything quite like The Dark Knight. And it likely never will again.

Photo: TM & ? DC Comics. ? 2008 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.