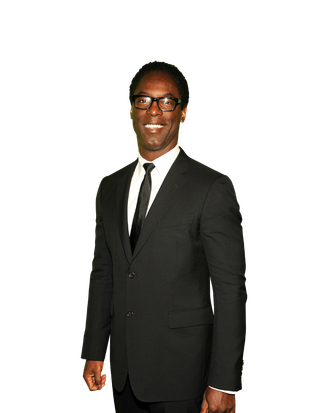

Blue Caprice is not the torn-from-the-headlines story you might imagine when you hear the movie is based on the D.C. Sniper case. Rather, director Alexandre MoorsÔÇÖs ruminative, quiet film is more interested in charting the emotional interaction between John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo, as the young, lonely Malvo gradually falls under the spell of the mercurial, mysterious, and charming older man. And as Muhammad, Isaiah Washington gives a beautifully modulated performance ÔÇö one both charismatic and cruel. It marks a triumphant return to form for the actor, who showed such early promise in films like Clockers and True Crime, but then seemed to flame out with his controversial 2007 departure from GreyÔÇÖs Anatomy. He talked with us recently about his new film, about researching the role of a ÔÇ£monster,ÔÇØ and about what life was like after he left GreyÔÇÖs Anatomy.

YouÔÇÖve worked with a lot of veteran directors over the course of your career. This is director Alexandre MoorsÔÇÖs first feature. Was it different working with him?

This was the first time where I worked with someone I trusted completely. I completely gave myself over to him and I knew he was going to do the right thing. That had never happened before, and I donÔÇÖt know if itÔÇÖll ever happen again. He didnÔÇÖt have a script when I agreed to do this film, man. IÔÇÖd just looked at his stuff on his website, and I kept showing it to other people, saying, ÔÇ£You have to check this out. This guy is truly a talent to be reckoned with.ÔÇØ He did ÔÇ£RunawayÔÇØ with Kanye. He claims he was just a creative consultant on it. But itÔÇÖs this beautiful video with this mega-talent and Selita Ebanks. And I watched it over and over again. IÔÇÖd watch it for hours. It was like drinking a cup of coffee. IÔÇÖd watch it whenever I needed a little jolt. I showed it to my kids and my wife. We were like, ÔÇ£Who filmed this? Who edited this?ÔÇØ

So, how did you and Alexandre find each other?

He found me, on Facebook. Apparently heÔÇÖd been looking for me for months. I donÔÇÖt have an agent, I donÔÇÖt have a manager. The way I see it, the people who really want to find me can find me. The guy that says heÔÇÖs my manager is really just a friend of mine ÔÇö whoÔÇÖs a former agent. If something interesting came to me, fine, but IÔÇÖve been busy traveling the world ÔÇö Turkey, Africa, Morocco. IÔÇÖve written a book, IÔÇÖve become a better husband and father because IÔÇÖm home every day. My connection to the Hollywood world has only been through Facebook. My followers would say, ÔÇ£NBC is looking for you. Law and Order: L.A. is looking for you.ÔÇØ So IÔÇÖd give the casting director a call, and theyÔÇÖd be like, ÔÇ£Is this really you?ÔÇØ Because theyÔÇÖre expecting to talk to an agent, and I havenÔÇÖt had an agent in six years. I do all my calls. I negotiate my own deals.

Why have you opted out of having an agent?

Opted out?! I didnt have a choice! I didnt opt out. Who wants to hire a monster? The phone wasnt ringing, bro. I didnt want to leave Hollywood. But the way the system works is that if people believe that youre a certain way, or they think you supposedly hate them  how can I expect them to take a call on my behalf if theyve been led to believe that Im this monster? And now, cut to: Now Im playing a monster, and everybody wants to represent me and talk to me. [Laughs]

You gave one of the best performances IÔÇÖve ever seen in Clockers, and you were so strong in films like True Crime, Bulworth, and Out of Sight. Watching Blue Caprice, it felt nice to have that guy back.┬á┬á

IÔÇÖve always been that guy. IÔÇÖm proud to say that I was that guy playing the character of Dr. Burke on GreyÔÇÖs Anatomy. IÔÇÖd never throw him under the bus. I would never say anything bad about that writing staff. They had so much respect for my film history. The average person in Hollywood just assumes that if youÔÇÖre on a hit TV show, then thatÔÇÖs the first thing youÔÇÖve ever done. A lot of people thought that was the first thing IÔÇÖd ever done, so when things went bad, a lot of people were like, ÔÇ£How dare he be so ungrateful? Off with his head!ÔÇØ But people who knew me from New York, from my career as a dancer ÔÇö people who knew me from when I was auditioning for Alvin Ailey, before I got hurt ÔÇö they were looking at the world, going, ÔÇ£You must be talking about the wrong guy. This is not that guy.ÔÇØ But my mistake was in trying to change that. In hindsight, you donÔÇÖt fight fire with fire, and you definitely donÔÇÖt try to correct something backstage at the Golden Globes. That is definitely not a smart idea. IÔÇÖll always regret that.

But things are changing now?

Think of it this way: The man that held $2.7 million from me begrudgingly, and walked me out the door at ABC, is the president of CW Network, which is now giving me an even bigger and better opportunity. IÔÇÖm working with Patrik-Ian Polk on Blackbird, which is a gay coming-of-age story that stars a newcomer playing my son. WeÔÇÖre dealing with issues of homophobia in the black church, in the black community, with teenage pregnancy, interracial relationships. Wait till you see that. IÔÇÖm producing now. WeÔÇÖve got a project called For Colored Boys, a web series about the incarceration of men of color and what it means to their families. I have a project about a veteran African-American train conductor, whoÔÇÖs witnessed twenty suicides by train over the course of his career. That means, on average, he kills one person every year at his job. I want to try to tell interesting stories about everyday people like that, and I donÔÇÖt want to tell stories with easy answers. I feel like sometimes Hollywood is so behind the times when it comes to the human condition. IÔÇÖm more interested in telling stories about whatÔÇÖs relevant in our world today than playing a slave or a butler. I know that history. IÔÇÖm proud of that history. I couldnÔÇÖt be more educated about what the struggles were for the African-American community.

What do you feel are the bigger, more relevant issues that films should be tackling?

ThereÔÇÖs something wrong in America, period. And if youÔÇÖre not convinced, just look at the violence that continues to this day. The issue of violence and how itÔÇÖs exported and even imported in America is why IÔÇÖm really proud to be part of a film like Blue Caprice. IÔÇÖm not really playing John Allen Muhammad the man. ItÔÇÖs a character, a narrative, as seen through the eyes of a filmmaker who lived in Paris, and as a child who always loved America, like I think we all do. We cannot be blind to the fact that thereÔÇÖs a character flaw in this country, collectively speaking. Why does it take unbelievable traumas ÔÇö like 9/11, or the North Ridge Earthquake ÔÇö before we can come together and support each other? I know it sounds corny and hackneyed, but IÔÇÖve had six years to think about this.

So, letÔÇÖs talk about the character you play in Blue Caprice. I agree with you ÔÇö it doesnÔÇÖt quite feel like this is John Allen Muhammad, but rather a more elemental character. It doesnÔÇÖt feel specific to the story.

I started doing research, and I had the bejesus scared out of me, from what I discovered about this man. He had a phase one, a phase two, a phase three. I found out that he was inspired by 9/11, that this was his own personal jihad, and that he wanted to bring the U.S. to its knees for what he considered the killing of Islamic people. And he thought he could do it better than anyone else. In his mind he was at war, and these people were collateral damage. And then you think about how our government deems other people collateral damage. That was the chilling part. I didnÔÇÖt want to look at him. But I felt responsible for that information, being former military myself. That then forced me to not look at him but to look at our world. I had to sit on the couch for two weeks after I researched this movie.

But the film goes beyond all that. ItÔÇÖs really about the relationship between this man and this boy.

I remember there was a scene between me and Joey [Lauren Adams], when Alexandre started crying. I stopped and I was concerned. What the hell is going on? My director is crying. And he did it more than once. Did something happen to his family? I couldnt understand. But now I do. The work that we set upon doing was extremely painful for him. To watch a character, or a man, simply do these things  this movie is really about fathering, and leadership. And whatever has happened in Alexandres life with his father, this film is a personal conversation with the world about how we look at our fathers. Good ones, bad ones, absent ones  its about what fathers do. We made a movie about a father and a son. But at the same time, its not what this movie is about, because of the events that its based on.

Do you keep in touch with Spike Lee?

Spike and I go back and forth, on Twitter and stuff. You know, heÔÇÖs really busy. Spike is always shooting a commercial, or prepping a movie, or doing something. I see now heÔÇÖs got Oldboy coming out, and heÔÇÖs out there fund-raising for another one. HeÔÇÖs like Clint Eastwood, who doesnÔÇÖt stop working. I mean, Clint just doesnÔÇÖt stop, at his age. You ask him and heÔÇÖll say, ÔÇ£What am I supposed to do, sit at home?ÔÇØ I bet heÔÇÖs shooting a new movie right now.

Actually, I think Eastwood is shooting a movie called American Sniper.

[Laughs uproariously] ThatÔÇÖs awesome! Well, thatÔÇÖs my former boss.