“Commit to the monkey!” Susan Stroman is saying. The director and choreographer of the new musical Big Fish—now in previews and opening October 6—is encouraging the show’s star to seize the simian moment in a scene they are rehearsing.

But Norbert Leo Butz, who kept what he calls “the worst name ever ever ever ever,” despite the dire warnings of a theater professor lobbying for “Bert Lee,” doesn’t need much encouragement when it comes to embracing indignity. Rather, with an almost manic energy, he heads straight for the terrain where sweaty and seedy intersect with stubborn, near the horizon of just too much. Following Stroman’s lead, he balls his hands into soft fists, drags them along the floor as he lopes, then improvises by picking imaginary nits from his crotch and (perhaps a step too far) eating them. After many takes, this will get simmered down to a second or two of stage time, as will the new lines and dance steps he worries over, fiddling endlessly to get their rhythms to lie flat.

Butz is spot-on casting for the marathon role of Edward Bloom, a charismatic southern rascal whose life is a string of evasions explained by a series of very tall tales. Butz, “46 and I feel it,” plays the character at various ages, switching in full view between the callow young man on the make and the dying father trying to reach his disillusioned son. (In the 2003 Tim Burton movie, the role was split between Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney.) Along the way, he leads big dance numbers and has touching love scenes and gets shot from a cannon. He also sings eight or nine songs: a bouquet that Andrew Lippa, who wrote them, describes as Gypsy or Evita size, and highly unusual for a man in a medium more typically focused on women.

A restless exploration of sex and gender is evident throughout Butz’s résumé, which is as notable for its preponderance of new work as for its bewildering array of types. Since arriving in New York seventeen years ago, he has played, to name just a few, both of the leads in Rent, the party boy Fiyero in Wicked, a violent husband in Fifty Words, the disgraced nerd-king Jeffrey Skilling in Enron, the shiksa-obsessed wunderkind in The Last Five Years, and a French painter in drag in the Mark Twain resuscitation Is He Dead? And while it may be no surprise that he won Tonys for his two showiest roles—the imbecile con man of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and the melancholic G-man of Catch Me If You Can—he also won Fred and Adele Astaire Awards, though he’s not exactly the soigné type, for his superb character dancing in both musicals.

Still, Butz is an odd Broadway star. Beyond certain precincts, hardly anyone knows who he is. He isn’t a TV or movie A-lister dropping in on New York now and then. (Hugh Jackman and Michael C. Hall were involved in earlier phases of the development of Big Fish.) Rather, he’s part of a small group of excellent singing actors who can anchor a $14 million show, if not presell it, and who have advanced the complexity of musicals (and nonmusicals) because of their unusual rather than generic leading-man traits.

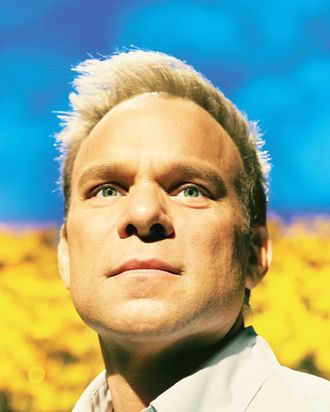

For starters, there’s his mug, as he calls it, with its deep-set, squinty eyes and receding hairline. He’s also just five-foot-seven. His singing voice does not have the typical Broadway man’s narrowcast focus but a powerfully masculine rock heft (with a huge range) that sounds like it could plow down stone walls. (Lippa calls it “the kind of voice that makes the world stop.”) And his native St. Louis cadence, discernible through whatever accent he puts over it, adds to an insinuating, hucksterish appeal. When Stroman first worked with him—on Thou Shalt Not, a Thérèse Raquin adaptation that flopped in the wake of 9/11—his talent was “really raw but exceptional,” she says. He has since grown into it and is now, she senses, comfortable in his own skin. “Many are not. Many wait for a character to get them through life. Norbert makes the character out of his life.”

If so, that’s a very good thing for the theater—because few actors have a background like his. The circumstances that brought him to success, and that have permanently changed him in the last four years, are so unlikely and in some cases tragic they would make a fabulist like Edward Bloom blush and then cry.

The first time he saw a musical on Broadway, it was because he’d been cast in it. This was in September 1996; Rent had opened that April, but its two male leads were having vocal problems and the man understudying both “wasn’t working out.” Butz, newly arrived in New York at the ancient age of 29, had no agent but attended an open audition; after five callbacks, he was offered the job. Two days later, he went on.

In a box overlooking the stage at the Neil Simon Theatre, where dozens of stagehands are assembling the Big Fish set, he tells this story somewhat reluctantly, worried that it might sound like a brag when it’s meant as a cautionary tale. In the midst of his first performance, he recalls, after he sang the anthemic “One Song Glory,” “the producers go backstage and fire the understudy right then and there. Later, I come off at intermission, getting slaps on the back—‘You were amazing!’—and the guy who’s just been fired crosses me on the stairs carrying his little makeup box and crying.”

He winces. “And that’s been my relationship with this business: so much moral ambiguity. I don’t know whether I’m built for it.”

The seventh of eleven children of a devout Catholic couple, he grew up “a landlocked midwestern kid” in a world where music meant mostly hymns and folk songs; his father crushed the LP of Meatloaf’s Bat Out of Hell the boys were enjoying one day and another time ripped up a tape of Dylan’s “Everybody Must Get Stoned.” Longing to escape, Butz gravitated toward what was illicit, which came to include not just rock and roll but theater. “I was a closeted actor,” he says. “I lived my life like a lot of my gay friends.” He did not tell his parents until he was leaving for college that he had secretly auditioned for and been accepted to the conservatory program at nearby Webster University.

A semester in London that stretched to a year and a half changed his idea of what acting might be; when he eventually returned to Webster, he was determined to do the kind of “difficult, valuable” work he’d seen Anthony Sher and Michael Gambon and Vanessa Redgrave doing in London. But most of the choices he actually made over the next decade were “the result of wanting to follow a girl somewhere.” One led him to the Nebraska Theatre Caravan, which toured “gymnacafetoriums” throughout the Plains. (“I played Malvolio all over the wild, wild West.”) Later, penniless after a breakup, he entered the M.F.A. program at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival. He stayed in Montgomery (where much of Big Fish is set) for five years: getting married, working in the classics, singing in dives, and furiously repressing his ambition.

“The jobs I had to take in my twenties, some of the people I lived with, some of the drugs I did, it’s a miracle I’m here,” he says. “And when I came to New York”—where he and his wife had two daughters and divorced—“I didn’t like the way I was. Dealing with this constant manic cycle of success and failure, acceptance and rejection, not to mention the lack of artistic control over so much of what you do. And the way I dealt with that was through bad habits of escape.”

Another wince. “It’s that old struggle with the idea that being an actor is not a legitimate way to make a living. It’s too insular, self-serving, appealing too much to the vanity. And so many people are so silly in the industry! Especially in the musical theater, where a lot of what I’m offered, a lot of what is in the market, is nonsense.”

It didn’t help that most of the shows from which he emerged with glowing reviews tanked at the box office. “I am the most successful unsuccessful actor in New York,” he says. “And I guess with that, maybe apparent only to myself, there started to be a very subtle but unmistakable whiff of entitlement, bitterness, jealousy. I was not respecting the work.” Which may be why, until recently, Butz spent his entire professional life lying about his profession. “If I was on a train or plane and struck up a conversation, and someone said, ‘What do you do for a living?’—I’d say, ‘I’m a music teacher.’ ”

Butz doesn’t like to talk about what changed him into the wholehearted actor he is once again. Even in a cabaret performance I heard on July 19 at 54 Below, in a show he put together called “Girls, Girls, Girls,” with a band called the Lady Boners and a set list of songs chosen to illustrate the treatment of women in classical myth and contemporary society, he does not mention it. When I later ask him about his saying, in his patter, that he looked forward to a world “where Athena will be a military woman without worrying about being molested, and Demeter won’t be in mourning, because there won’t be rape,” he responds with surprise, insisting he never made the connection to his own tragedy. If so, he has very strong defenses, because he was wailing those songs about furies, muses, MILFs, and crones four years to the day after it happened.

In the predawn dark of July 19, 2009, he was in Seattle; Catch Me If You Can was set to begin previews for its pre-Broadway tryout at the 5th Avenue Theatre on July 25. As it happens, his 39-year-old sister, Teresa, lived about seven miles from the theater, in the rough, ramshackle South Park neighborhood. The night was warm, so she and her partner, Jennifer Hopper—they planned to marry that September—left a few windows open to admit a breeze.

Around 3 a.m., a 23-year-old man named Isaiah Kalebu broke in, closed the windows, and, over the course of 90 minutes, alternately and repeatedly raped both women and savaged them with knives. The full record of this crime is remarkable not only for its abject horror but for the bravery of the women. Teresa eventually managed to break a window with a metal nightstand; naked, she made it out to the street, where she died almost immediately of the stab wounds to her heart. But the distraction allowed Hopper to escape as Kalebu fled. As a result, Hopper lived to see Kalebu caught five days later and to testify at the trial that convicted him in July 2011. That August, he was sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole. Hopper had not wanted Kalebu put to death; Teresa’s father, on the stand, said he’d forgiven him.

For a grieving brother who came “very close to losing myself completely,” the grinding work of opening a show—the first Seattle performance of Catch Me was delayed only three days—“was a salvation.” But so was being part of a theatrical community, and so was performance itself. At the funeral, he and Hopper and other family and friends sang hymns and favorite tunes of Teresa’s. Out of this spontaneous outpouring came a fund-raising CD and, later, the Angel Band Project, which supports survivors of sexual violence with music therapy. On the CD and in recent benefit concerts for Angel Band, Butz sings two Patty Griffin songs, including one with this agonized lyric: “I wonder if there was some better way to say good-bye.”

That wondering gradually infiltrated everything Butz did. He gave up drinking and “all controlled or uncontrolled substances”; he began to look more gratefully on his career. (He no longer pretends to be a music teacher.) Playing the pedophile in Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive last year at Second Stage was in part a way of merging his grief with his work and using what’s unique to theater to address, at least internally, issues that had become crucial to him.

More recently, he has made the connection overt. In May, after receiving an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, he seemed to surprise the graduating class with a commencement address that asked them to “help end the culture of violence against women on television, in music, in homes and public parks and backseats of cars all over America.” He suggested they begin by not including such entertainment in their Netflix queues and gaming downloads. At the very least, he urged that they should “change the channel.”

If even that small gesture may be an unrealistic goal, he feels he has no choice but to ask. His daughters with his first wife are now 13 and 16; he also has a 2-year-old daughter with his second. “What happened to my sister is not extraordinary,” he says; his teenagers have already been groped and verbally harassed at school or on Facebook. Noting that one in four women on campus will be the victim of an unwanted sexual advance, he all but shouts: “One in four? I have three daughters! If I’d have one more, I’d really be fucked.”

As a result, in the last year, he told his agents and manager that he could no longer audition for “material that uses the rape, mutilation, or murder of a woman for the purpose of adding suspense to a plot, to tease or titillate an audience when the narrative gets boring.” Though he’s hardly in a position to snub lucrative jobs, and he fears seeming “super-noble” even discussing it, the result has been eye-opening. Under the new restriction, he has had to reject almost every film and TV script—mostly police procedurals and serial-killer dramas—he’s been offered.

And though theater is hardly exempt from his disapproval—Butz particularly loathed two recent plays in which he watched “women getting the shit beaten out of them”—he now sees how he can use his success to make sure his work supports his values. He says (and Stroman happily confirms) that he engages in “robust conversations” with his directors and creative teams, not only to make sense of his character but also to make sense of the message. In Big Fish, the result is a role not so much tailored to as extruded from him: a workaholic salesman (Butz’s father, also named Norbert, once sold insurance door-to-door) whose great charm does not quite paper over his need to prove something about the value of his dreams. Regardless of whatever else is going on in a show, Butz now makes sure he has a coherent story to which he can give himself fully, which is why his acting, singing, and dancing seem, more than ever, to be hewn of one solid chunk of humanity.

But what is that story in Big Fish? “I know we’re supposed to say it’s a musical about living big and dreaming big and blah blah blah,” he answers. “But really, it’s a meditation on death; there’s no other way to say it.” He smiles sheepishly but barrels on. “A big, gorgeous, emotive, vibrant, and entertaining meditation on death.”

*This article originally appeared in the September 30, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.