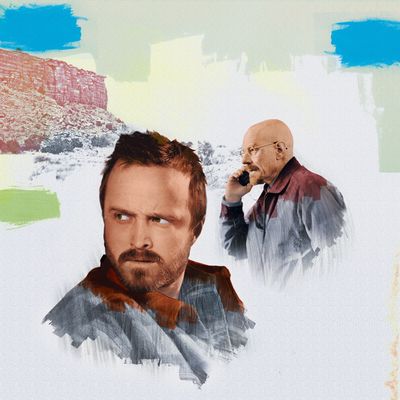

Walter White goes free. Walter White redeems himself. Walter White dies of cancer. Walter White gets buried in the desert and eaten alive by ants. Walter White goes to the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks and has coffee and pie with Special Agent Dale Cooper.

One of these potential endings might satisfy you, or none might. But Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan and his collaborators had to come up with something to finish their AMC crime drama, which airs its series finale September 29, and may or may not collect the Emmy for Outstanding Drama Series on September 22. The end is a show’s most important moment, because it retroactively shapes what we think about everything that came before it. Audiences understandably crave answers to the basic questions. Can Buffy ever return, or is this the end for her? How will all of the conspiracy threads on The X-Files tie together? What were Lost’s smoke monster and golden pool about, and was the show’s “sideways timeline” real or glimpses of an alternate universe? But they want answers to the big questions, too: What was this show trying to say about human nature, about society, about life? Was it ever saying anything? Did it deserve all the time and emotion I invested in it?

A satisfying finale was no small achievement even in the pre-Sopranos era, when most episodes of shows played like self-contained stories rather than chapters of an ongoing serial, but some managed to pull it off. The snow-globe pullout that ended St. Elsewhere is still a head-scratcher, because it implies that the globe’s owner is a child who somehow knew everything there was to know about medicine and TV history, but it’s of a piece with the surreal randomness that fueled that great eighties drama. The end of Newhart was delightfully humble: By having Newhart wake up in bed next to Suzanne Pleshette and realize the whole thing was a dream, the finale tacitly admitted that, whatever the sitcom’s charms, it was no The Bob Newhart Show. The Cheers finale lent sneaky heft to a light comedy by peeling away the major characters until womanizing hero Sam Malone was left in the bar. The closing scene confirmed that Cheers was to some degree about loneliness, or aloneness, and the necessity of seeking happiness within. The jail-cell payoff of Seinfeld, on the other hand, divided fans. It confirmed that the creators did, in fact, have a point of view on all the petty monstrousness they’d shown us, but some viewers balked at the implication that by enjoying the characters’ bad behavior for nine seasons, they were virtual accessories after the fact.

In the mid-nineties and early aughts — the heyday of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Sopranos, The Wire, Battlestar Galactica, The Shield, and other dramas driven by mythology, long-form storytelling, or both — a new conundrum presented itself: How to sum up an experience that has made a point of saying, “I am large, I contain multitudes”? The great modern TV drama is not a discrete, self-contained story, like a movie, a play, or a novel. It’s a living thing that grows and changes over time. It’s subject to the vagaries of production: A certain actor wants out of his contract; a producer has to be fired because he’s always late delivering episodes; the star is tired of working in Vancouver and wants to shoot in Los Angeles. (The latter isn’t a hypothetical: It happened on The X-Files.) Making television is not merely an artistic endeavor but an athletic one: a display of in-the-moment ingenuity and endurance. The answer to the question “Did you have a plan, or were you making it up as you went along?” is always “Both.” Gilligan’s Breaking Bad writers, for example, realized midway through writing season three that they weren’t happy with the story’s direction, so they killed off their two main antagonists and focused on a new one. Gilligan’s crew did a lot of this sort of thing in seasons three through five, and because they’re Carol Burnett–level masters of Acting Like They Meant to Do It, and equally good at cleaning up loose ends after the fact, the show hangs together better than it probably should.

The post-Sopranos dramas embraced these built-in aspects of chaos, telling viewers, “Neat storytelling is not the only valid kind of storytelling.” But then the ends draw nigh, and the shows are expected to deliver a socko, all-questions-answered finale and pretend that they always planned to end up in that place, by that route, on that timetable, by way of a map they’d drawn years ago. Incredibly, some modern programs achieved this preposterous feat. The end of The Wire, for instance, felt structurally and philosophically right because its layer-cake drama was built on the foundation of one basic question: “Why do our institutions fail us?” The last half of the finale hazarded an answer: “Because institutions are run by people, and people are flawed and weak and easily discouraged and tend to reach a point where they’d rather give in than fight.” Other series had a harder time. Fans still grumble that the endings of Lost and Battlestar Galactica were too mystical or too obscure — or worse, a payoff that made them regret the years they spent watching.

It’s probably especially hard to write an ending for an anti-hero, like the ones on dark post-Sopranos dramas such as Breaking Bad, Dexter (which ends September 22*), and Mad Men (which enters its final season next year, and will compete with Breaking Bad at the Emmys), because a big part of such shows’ excitement comes from the dual pleasure of simultaneously loathing and cheering the protagonist. Old audience habits die hard: For all David Chase’s innovations in attraction-repulsion storytelling, a lot of viewers still seem to think that a “satisfying” ending is one that punishes destructive characters, as in gangster films of yore. To quote a commenter on one of my Breaking Bad recaps on Vulture, “It will end with Justice or No Justice, so to speak. It will be the creators’ and writers’ final say on what they believe.” No pressure or anything.

There are big problems with both “justice” and “no justice” endings. If the anti-hero is punished, the viewer is guilty by association: the Seinfeld effect. But if the anti-hero is let off the hook — or has to “live with himself” — the show can seem amoral, or at least wishy-washy. Even a more nuanced or ambiguous nod toward one end of the scale or the other could backfire, seeming to neaten up a worldview that was intriguingly complicated. On top of all that, there’s the vision thing: Endings put a frame around the story and suggest why it was told to us, and what we should take away from it. If the anti-hero walks free, some might think the creator is a cynic, or a provocateur testing our moral compass for years but declining to say what direction the show was really headed in. Gilligan has addressed all this in the run-up to the finale, telling Vulture that he understood and shared the audience’s “yearning” to see “bad people” punished, but that he didn’t “feel any real pressure to pay off the characters, morally speaking.” He sounded blasé, but anyone who’s spent time around writers knows how agonizingly hard it can be to devise the one and only perfect ending. If there were a drug that treated choice paralysis, every writer’s room in Hollywood would be packed with addicts.

In addition to its virtues as puzzle and provocation, The Sopranos’ ending also represents an end run around the problems outlined above, though, of course, that’s not why Chase chose it. Any grousing about Chase making us write an ending for him was eventually subsumed by appreciation for that finale’s sheer audacity, as well as the larger questions it provoked. It felt fresh and singular, so much so that it’s hard to imagine any subsequent drama attempting an enigmatic ending without coming off as a pathetic Sopranos wannabe. And really, the vast majority of viewers don’t want that kind of ending. They’re not watching for the aesthetic ambition, however much they may appreciate it; they’re watching for the story and the characters. While they may not demand that the ending be tied up in a neat little bow, they won’t turn one down if it’s pretty, and tied with skill. And when the show is done, they want to move on. Yes, people want art, but more than that, they want answers, and finality. It’s not wrong to want these things. It’s human.

Curiously, though, television history is littered with countless examples of what you might call an accidental cut-to-black: finales that were never intended as finales, but served that function because the shows were canceled, and that in some cases grew to seem perfect, or at least backhandedly satisfying. Sometimes this is because the writers learned that cancellation was certain or likely and wrote a season finale that doubled as a series finale. Other times the feeling of closure is just a happy (or unhappy) accident. The closing episode of the one-season wonder Freaks and Geeks, which showed the academically gifted heroine ditching the “straight” life to go follow the Grateful Dead, works fine as a series-ender. The end of Deadwood is perhaps an even more dramatic example of a non-ending that feels somewhat like an ending. David Milch’s Western drama was meant to run five years but got axed after three. The program inadvertently ended on a despairing note, with the forces of commerce lording it over the show’s Milch-style loquacious outlaw anti-hero: If nothing else, it felt like an oblique admission of why there were no more episodes of Deadwood. Like the endings of so many prematurely canceled series, it wasn’t ideal, but it had to do, because that’s where the curtain fell. That’s how life is, in a way: It’s ultimately about coming to terms with death. Some deaths you see coming. Others appear without warning. An end is an end is an end.

*This piece has been updated to correct the date of Dexter’s series finale.