Vulture is taking you to film school this week, and we’ve got a great faculty. In our new series How to Make a Movie, some of film’s most accomplished artists from a wide array of fields will be explaining their techniques. The Heat’s Paul Feig will teach you how to whittle down hours of improvised hilarity into one movie. Gravity director of photography Emmanuel Lubezki will give a master class on cinematography through five of his most dazzling shots. Diablo Cody will reveal the five things nobody tells you about being a top screenwriter. Superhero-costume designers, prolific film composers, savvy producers: All week long, they’ll be giving imperative advice on how they do what they do. The series kicks off today with an in-depth interview with Wes Anderson on the making of one of his most beloved films, The Royal Tenenbaums.

On Tuesday, New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz will release his sumptuous coffee-table book, The Wes Anderson Collection. The book delves deeply into each of Anderson’s seven films, dissecting every angle and influence with commentary, illustrations, and photography. Every chapter is anchored by a lengthy conversation between Anderson and Seitz about the making of each film: The Tenenbaums chapter, excerpted here, covers everything from finding the perfect Tenenbaum brownstone to Anderson’s trademark shots to recruiting a reluctant Gene Hackman for the role of reappeared patriarch Royal. Follow Anderson’s lessons to find out how to make a masterpiece of humor and melancholy. (And see a gallery of behind-the-scenes pictures from the Tenenbaums shoot here.)

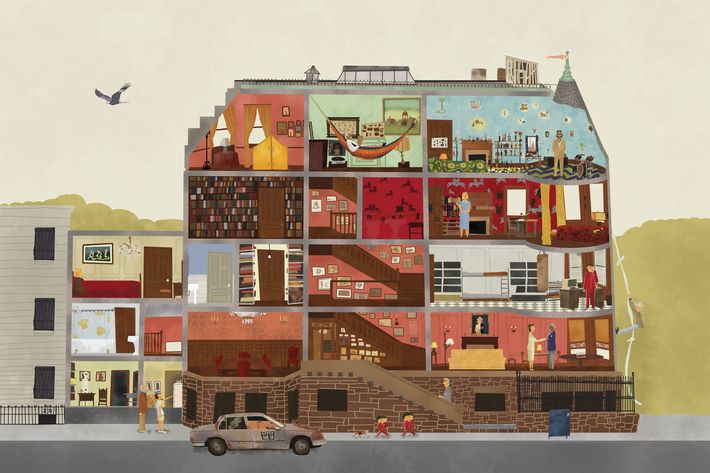

Let’s talk about the spaces in The Royal Tenenbaums. Let’s talk about the house. Where is the house? Are the exterior and the interior the same house, or did you shoot those at different places?

No, it was a real house. At the time I was very adamant that this would be a real place and that we have to make it a real place. The movie’s scheduled around the actors — it’s a little jigsaw puzzle. We have Ben for these three weeks, and we have Gwyneth for only these ten days, and everything is built around that. I felt like they had to have this real place that exists that they can walk into and say, “This is my room. Here’s my room.” And they did. It was also quite practical, I think. The roof was the real roof. It was all one place. The only cheat was with their kitchen, which was in the house next door, because this place had no windows—it was not going to work. But the rest of it’s all there — it’s near Convent Avenue and 144th Street in Harlem, just north of City College. The hotel where Gene Hackman is living at the beginning is the Waldorf.

Were there any places in the movie that were wholly invented, where you built a set? Did you build any sets?

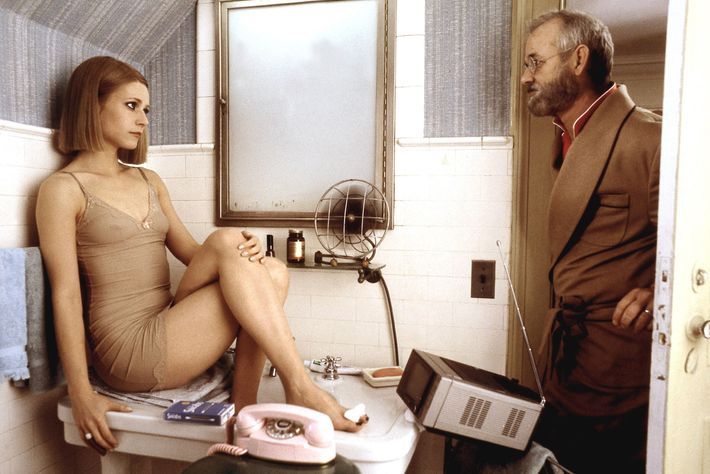

Well, let’s see . . . no. You know, we built the archaeological site, but they’ve had plenty of those in the city. Everything’s kind of inspired by something, and everything’s done in some converted place. For the 375th Street Y, the exterior was in one place on the Upper East Side, and for the interior we found a place in New Jersey. I can’t remember where. I can’t remember what it’s called, but somewhere in Newark there was this big abandoned hospital, and we made our hospital in it. We also found a mansion in Yonkers that we used for many things—Gwyneth in Paris in one little corner, the bathroom of Gwyneth and Bill’s apartment in another, and Gene’s doctor’s office in another. But anyway, the 375th Street Y—the place where they lived—that was in New Jersey.

Talk to me about Orson Welles and The Magnificent Ambersons. That house looks an awful lot like the Ambersons’ house, and I’m assuming that’s just a lucky accident.

Well, a lucky accident, but probably also because it was in my mind. The Royal Tenenbaums was really inspired by The Magnificent Ambersons more than anything, but it’s the one film I haven’t even thought to mention so far. But yes, I found the house with my friend George Drakoulias.* We were driving around, and one other person was with us, my assistant Will Sweeney. And George was on the phone, and we were walking around an area in New York called Hamilton Heights, and George said, “I think you might look up the street. There’s a place up there.” And I walked up there, and what I probably saw was a house that looked just like the one in Ambersons, and I thought, “That’s the place.” And I also saw a sign in the window that said it had just been foreclosed on, so I thought, “Well, what state is this going to be in?” What happened was that a guy had just bought it after it was foreclosed on for the amount that we ended up paying him to use it. He got the house, ultimately, at no cost, because our fees for shooting there ended up being the equivalent of what he paid for it.

He had a very good year. The story of The Magnificent Ambersons is also—

It’s faded glory.

It’s the decline of a once-great family.

I guess that movie and the Glass family stories, and also You Can’t Take It with You. And another: Kaufman and Ferber’s The Royal Family. Maybe those are the other principal parts.

I haven’t seen or read The Royal Family. What happens in that?

That one is modeled on the Barrymore family, a theatrical family. There’s a movie, which is The Royal Family of Broadway. The mother is the boss, and there’s this son who’s a rogue young actor like John Barrymore. Frederic March. Anyway, that’s the milieu.

Do you remember the first Orson Welles film that you saw?

I think it might have been Touch of Evil or The Lady from Shanghai. Even before I saw Citizen Kane, I think I might have seen those. He’s always been one of my very favorite directors. I love The Trial, and I love Anthony Perkins in The Trial. The Trial is fantastic, and very underrated. It’s a part of Welles’s European phase, when he was having trouble getting money together, and one of the things that’s fascinating about it is that you can kind of see the production disintegrating as it goes along, as if the money is running out on-screen as you watch.

I think originally they were going to shoot the entire thing on sets. And then they got the opportunity to shoot at the Gare d’Orsay**, which was closed — before it became the museum. But those exterior shots, the shots of the outskirts of Paris, those buildings — you know those wide shots where the buildings are tiny in the background?

Yes!

I love those.

Very deep focus, very, very crisp images, and almost a sense of distortion, you might say, with the edges of the frame bowed.

It’s very kind of . . . “expressionistic,” I guess is the word.

What are some qualities of Orson Welles as a director, or simply as a storyteller, that you enjoy?

He’s not particularly subtle. He likes the big effect, the very dramatic camera move, the very theatrical device. I love that! And then also, he loves actors, and he is an actor himself, and he always created great characters that also tend to be larger than life.

There is a Wellesian sensibility in certain parts of certain films of yours.

Well, that would be great. He’s one of my heroes.

Welles, Godard, Hitchcock, Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese — what, if nothing else, do these filmmakers have in common? They are not simply people behind a camera. You are aware of them. You feel the hand of the storyteller guiding the story when you watch their movies. And sometimes you actually see them, on camera, in the movie.

Roman Polanski is another name you should add to that list. He is also both things.

We haven’t seen you, I don’t think — you, Wes Anderson on-screen, except in that American Express ad you did many years ago. We see your hands stamping the card in the library book at the start of The Royal Tenenbaums. We’ve seen your drawings, your sketches. You’re one of the voices narrating Richie’s tennis court meltdown in The Royal Tenenbaums. You were the voice of Weasel in Fantastic Mr. Fox, and you acted out a lot of the characters’ motions for the animators.

Well, maybe “acted” is too strong a word. Part of how I would communicate with the animators, and with the director of animation, was to make little videos, but it wasn’t meant to be a performance. It was just meant to communicate certain things that the puppets could do. But sometimes a gesture is hard to describe. You have to sort of do it for people. If the gesture is like, “I’ll meet you on the other side,” I could show them a gesture that means that a bit more easily than if we sat there talking about it until we both figured out that we were talking about the same thing.

Have you ever studied acting?

I was interested in acting when I was a teenager. And I acted in plays and things like that. But it’s not something I’ve ever wanted to do as an adult. I always wanted to write and direct. I’m lucky enough to be able to get some of these movies made. I went down this path, and I don’t see any need to diverge from it.

No mid-career change in the works, I suppose.

No!

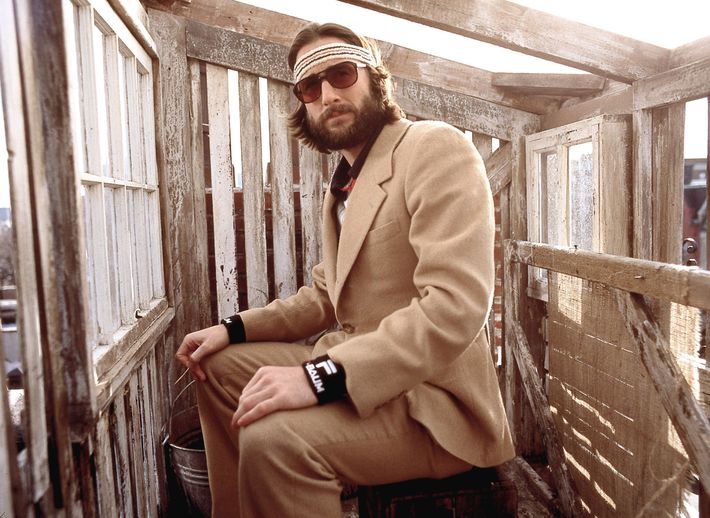

The characters in The Royal Tenenbaums all wear their personalities on the outside, I think perhaps to a greater degree than in any other movie you’ve directed. You know, Richie is still wearing the tennis headband.

Keeps the sweat off.

And Margot has got that “stay away from me” makeup and the cigarettes and everything. All these characters, they look like they could be New Yorker cartoons or something.

Hmm.

Did you actually draw them beforehand? Did you do any sketches of them? Did your brother, Eric, do anything?

I did have Eric do drawings of the characters at one point, because I wanted to send a drawing to Gene Hackman. I was trying to convince Gene to do the movie, and I had Eric draw this illustration that showed what all the actors would look like, with Gene’s character in the middle, and it had a couple of people who were not actually cast in the film. But I sent him Eric’s original artwork, which we shouldn’t have done. We should have scanned it and sent him a good duplicate. Because later I asked Gene twice if we could borrow that drawing, and I fear I think he threw it in the trash.

Oh my God!

He couldn’t find it, anyway.

Oh dear.

Maybe Gene just didn’t want to loan it back to us. But anyway, it had some of the wrong cast, so we probably couldn’t have used it for whatever our purpose was.

Gene Hackman — it was always your dream for him to play Royal?

It was written for him against his wishes.

I’m gathering he was not an easy person to get.

He was difficult to get.

What were his hesitations? Did he ever tell you?

Yeah: no money. He’s been doing movies for a long time, and he didn’t want to work sixty days on a movie. I don’t know the last time he had done a movie where he had to be there for the whole movie and the money was not good. There was no money. There were too many movie stars, and there was no way to pay. You can’t pay a million dollars to each actor if you’ve got nine movie stars or whatever it is — that’s half the budget of the movie. I mean, nobody’s going to fund it anymore, so that means it’s scale.

Was it actually scale?

Yep.

Wow.

Yep. But eventually, his agent wanted him to do it. He was close to his agent. And he came around, and he did a great job, I thought. I mean, I was just very excited to have him.

In addition to a lifetime of technique, he also is an iconic actor. You talk about you and Owen Wilson kind of worshipping at the altar of sixties and seventies American New Wave — he’s one of the guys.

He’s one of the guys.

I mean, was that part of the reason why—

No, I don’t think so. No. It’s just that the part wanted a legend, but really beyond that, it was just written for him.

Literally, or did you realize that after you’d written it?

No, it was written for him, literally. It was during the writing. I told him before. I met with him before. I called his agent and said I wanted to meet Gene because I had this thing I wanted to write for him, and he said, “Well, I’ll talk to him, but he won’t meet you until you send him the script.” And finally he agreed to let me meet him, and it didn’t help.

What was the meeting like?

He was very nice. He was very reserved. He said, “I don’t like it when people write for me, because you don’t know me, and I don’t want what you think is me.” And I said, “I’m not writing it for what I think is you — I have a character. I’m writing for you to play it.” But when it came to him, he didn’t want to do it. If we’d gone to him with an offer of anything like what he actually gets paid, then maybe it would have been easier to get him.

You certainly give the legend his due in the movie. You’ve got a little nod to The French Connection thrown in for good measure.

What do we have? What’s our French Connection thing? I mean, I thought of The French Connection often.

There’s the go-kart homage during the “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” montage.

Ah. Yeah, they have dogfights, and there’s a lot of French Connection–period New York.

And also just the whole sense of Royal Tenenbaum introducing people, introducing the grandchildren, to a less managed way of life, a more dangerous time.

Hmm.

He’s bringing the danger back.

Right.

He’s a visionary character, this guy, in his way. I mean, he’s certainly a strong-willed character.

Right.

And there’s no other character in the movie that has that degree of outward-projected force.

Right.

You have those types of characters in your movies a lot.

Hmm. There’s usually a talker in the middle of it somewhere, trying to get everybody riled up.

You don’t seem to be that type of a person yourself, though.

You know, I do like to get the group together and say, “Let’s give it one more try.” I do like to have a kind of project going with a company, but that’s probably the extent of it.

Let’s talk about composition and moving the camera. You do a lot of cutting in camera, and I think it reaches a peak with The Royal Tenenbaums. Do you prefer to cut with the camera whenever possible?

You mean doing a take without cuts?

Well, yes — realigning the viewer’s position within a take, but without actually physically cutting.

I do like that.

Take us there.

I asked you to clarify because sometimes when we were doing Bottle Rocket, I was often told, “Don’t cut in the camera,” which meant that — I think there’s an old Hollywood way of cutting in the camera, which is where you shoot the close-up for just, say, two lines. A scene might be four pages long, but you shoot the close-up for just those two lines, and you shoot a wide shot for the rest of the scene, so that you’re only getting those two shots for that scene. You’re going to use the wide shot, and you’re going to use the close-up for those two lines. So you’ve just got these two shots, but you haven’t got “coverage.”

That’s the way Hitchcock used to shoot, deliberately, so they couldn’t recut his movie.

Right. And I think John Ford. But anyway, I guess I do always like the longer takes. For me, there’s suspense in it. I just find it thrilling. But I don’t know — for most audiences, I guess it’s probably not having that effect, because they don’t notice it. But maybe it does affect them anyway. I mean, maybe they can feel that this is a real thing.

Well, I know I can, even though I didn’t know what it meant until I was older and I had seen more movies. I wrote a column one time about the first movie I ever saw that made me realize that movies were directed, and it was Raiders of the Lost Ark. And one of the scenes I remember being quite struck by is the drinking contest scene, where Marion is drinking that guy under the table. It’s all

one take.

Ah.

That’s another example of Spielberg, the silent master of the long take. No cuts in that thing.

Right.

Lateral pans down to the glass, up to the other person, down to the glass. And so on and so forth. It goes on for a couple of minutes, and I think it’s one of the reasons that scene is so tense.

Right. You’re not only waiting to see who’s going to get knocked out with the liquor, you’re waiting to see who’s going to screw up the take.

Even if you’re not thinking of it that way as a viewer, it works on you subliminally.

Well, that’s certainly the experience when you’re watching a complicated take being played on the set, anyway. Everybody involved in it is just waiting to see “Are we going to get through this one?” Usually, something goes a little bit wrong. And also when you’re shooting stuff like that — I mean, at least in my experience, anyway — it’s always twelve takes before you have it, before it’s good. If it’s very complicated, it takes a long time of really doing it before everybody can get it timed out and fix the technical problems. It just takes so much practice. But obviously, it depends on how complicated it is.

One of the most exciting times I ever had at a movie was when I saw Secrets and Lies at the New York Film Festival. There are two long takes in that movie that are static. One is the first meeting between the mother and her daughter, who had been given up for adoption, at a backyard picnic, with the entire extended family around one table. Both of the scenes play out for several minutes without a cut.

Hmm.

Both times, the audience applauded when there was finally a cut.

Really?

I’d never seen that before.

For just the performance of these moments?

Yeah.

Wow.

And, you know, when the audience is applauding the filmmaking, it’s quite a different thing from when they’re applauding the hero beating the bad guy.

Right.

It’s a different thing, and I also experienced it with the mountaintop battle in The Last of the Mohicans. I saw that with a paying crowd on the opening weekend, and Magua fell into the frame — dead — and they broke into applause. And it wasn’t about “the bad guy’s dead,” because he wasn’t a traditional bad guy. It was more like when a great symphony has been concluded, you applaud that orchestra.

Wow. Pretty good.

There’s a long take, cutting in camera, in The Royal Tenenbaums — Margot and Eli on a bridge.

It’s a pedestrian bridge. I want to say it’s on the edge of Harlem, but it’s more like Spanish Harlem. Anyway, it’s on the East River. Right, that’s a peculiar one.

Are you able to see a whole movie in your head? How it ought to be? Cuts and everything? Some directors put it together in the editing room. I mean, everybody has to edit, but you don’t strike me as somebody who has just—

No, I usually have a pretty good idea. I can definitely think up a way that a particular scene can be shot and cut in advance. Doing Fantastic Mr. Fox was a situation where I could think it up and that’s what we did, but shooting live action, especially on location, can complicate those ideas.

Usually, you may have an idea of how it ought to be done, but you may not know the location, so it just ends up having nothing to do with what you planned — actors do something unexpected, they surprise you, which changes the idea, or a question comes into the equation, or the space is just different from what you planned, and you’re going to have to deal with it differently. Or there’s something about the space that makes you change your plans. In The Royal Tenenbaums, I remember there was a scene where we had it figured out for ages, and on the day of shooting, these people would not, their window was reflecting—

What scene is this?

It’s the scene where Gene Hackman gets swatted by Anjelica Huston. He’s telling her, “I’m dying. I’m not dying. I’m dying.” And anyway, this house they’re supposed to talk in front of, they wouldn’t let us do anything to make it so the window wasn’t going to reflect directly into the camera. They wanted to charge us a lot of money for that. And I ended up saying, “Do we control this part of the sidewalk here?” “Yes, we control that.” “Can we lean a mattress against this tree, and we’ll block that whole part there?” “Yes, we can do that.” So then when we do the scene, Gene comes out, and he stops behind the mattress. You can’t see him. I said, “Gene, can you — is there a way to do it so you’re not hidden behind the mattress?” I feel the seething begin. He says, “Move the mattress.” “Well, see, Gene, these people will not let us do the scene. If you can find a way, what I’m thinking is you can just kind of use this mattress as your entrance.” I thought I was going to get socked in the face. He made it work, but the staging of it was completely dictated by the people with the window.

How often does that happen?

In different ways, it happens all the time. It doesn’t happen on an animated film. But on an animated film, what happens is that you say, “I want him to walk up the hill, stop, and talk,” and ten days later, you’re saying, “Why can’t we get him to walk up the hill? It looks ridiculous.” You know, he takes three steps, and you say, “This looks too weird.” Something that just seems simple is suddenly bizarrely impossible. There’s no gravity.

The annotations on the screen go to a whole new level in this movie.

In this one we’ve got a lot of them, because we’ve got all the ones in the flashback, or whatever you call that thing in the beginning.

I would call it a prologue.

It is a prologue; I think it’s actually called that. In fact, sometimes I think back on how I did certain things and think, “Now, that’s odd that I made that decision.” Like, you see the actual printed pages of the books, but the chapter titles are superimposed on them; the text and the spot illustration are printed on the page, but then it says “Chapter Two,” or whatever. “Prologue” — that’s a movie title. Why did I do it that way?

Why did you multiply the book covers? You have book covers and other pieces of art that are multiplied in almost a mosaic pattern.

Well, for those, I know why I did it that way. I saw that in Two English Girls, which is another movie that was quite a big influence on Tenenbaums. In that film, Truffaut takes copies of the book and fills the frame with them. The thing is, I thought Truffaut just did that because he had twelve copies of this book. We had to physically make each copy, so I could have easily just said that in our case, we can just have the one, but I wanted to do the mosaic thing.

It seems fitting, given the multiplicity of characters and plots — it’s almost too much of everything.

Also the other thing you could say is, “Well, if we don’t fill it with books, we’ve got to put something else in there.” A book is shaped like this, and the frame is shaped like this — what else is going to go in there that’s not going to take away from this part here? Well, how about the same thing over and over again? That will do it. Yes.

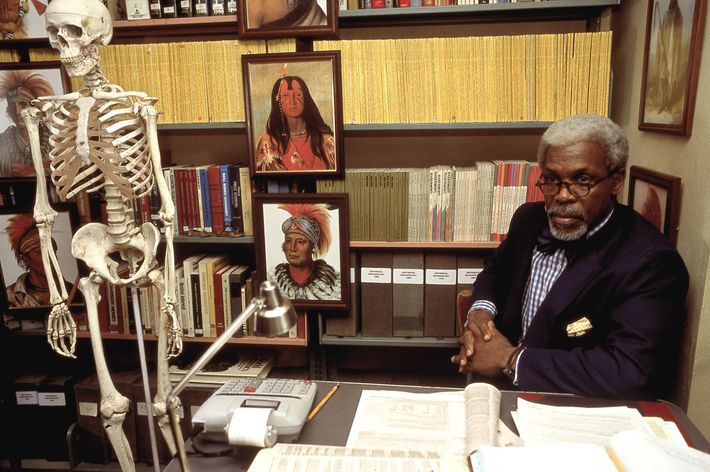

How did Danny Glover come to be cast in The Royal Tenenbaums?

I had particularly loved him in the Charles Burnett film To Sleep with Anger, which he’s so great in, and also Jonathan Demme’s Beloved. But he’s also great in Witness. Do you remember him in that?

I remember him vividly.

You always remember him vividly.

The first thing I remember is the scene where he and the other dirty cop murder that guy in the men’s room at the train station, and he’s at the sink, and the other guy says, “We gotta get out of here,” and he looks at him very coldly and calmly and says, “I’m just washing my hands, man.”

He’s great! In fact, I think we might quote a scene from him.

From Witness? In The Royal Tenenbaums?

I think in The Royal Tenenbaums, it’s not Danny’s line, but in that movie I think Danny shoots Harrison Ford in the parking garage, does that sound right?

I think so, yeah.

And Harrison Ford, after he’s shot, says, “I know you, asshole!”

That’s right!

And Gene Hackman says that in Tenenbaums: “I know you, asshole!”

Though Danny Glover is a classically trained actor who’s played a lot of diverse roles, he became a star in thrillers, military dramas, and action-adventures. He was one-half of the cop team in the Lethal Weapon movies. But in Tenenbaums you cast him as a peaceful, somewhat repressed gentleman in a bow tie.

You wouldn’t normally think of Danny as an accountant, because he’s a very dynamic person. And he has an artist’s personality in every way. Yet in Tenenbaums he’s playing a guy who is the opposite of that, really. But he has a kind of gentle manner, and he’s also a very conscientious person. So there is definitely a part of him that relates to this role. The guy he’s playing is nowhere near as cool as Danny Glover is in real life. Henry Sherman is awkward, he’s clumsy. But nevertheless, he’s got — what would you say? There’s something of Danny Glover in the role.

There is a gravitas to Danny Glover that comes through even when he’s falling into a pit.

Yes.

Gwyneth Paltrow is excellent as Margot, a role that seems to awaken something very deep in her. And it occurred to me that you’ve got Paltrow, whose mother is Blythe Danner and whose father was the beloved television director Bruce Paltrow; you’ve got Anjelica Huston, descended from the Huston family; you’ve got Ben Stiller, son of the performers Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara. And then you’ve got Luke and Owen Wilson, sons of Laura Wilson, a notable American photographer. That’s a lot of anxiety of influence gathered in your main cast.

That’s true.

Was that part of the plan, or is that just how it happened?

Well, probably it’s part of what draws you to them and makes them seem right for the parts — it all gets woven into it. And also, Royal says, “I’m mick-Catholic, but the children are half-Hebrew,” something like that. He has some line like that. They’re half-Jewish, half-Irish, is the idea.

Yes.

Well, that’s what all these actors sort of are. Stiller and Meara: I think that is Jewish-Irish.

It is.

And the Glass family in J. D. Salinger’s stories—that’s what they are, too. And it all kind of gelled and took that shape.

How did Anjelica Huston end up in the movie?

I’m a great fan of Anjelica’s, but in particular of The Dead and Prizzi’s Honor and The Grifters. I think those movies were the ones that made me want to use her. Plus, she’d been in Crimes and Misdemeanors, and she was very good in that. I wrote her part for her, too, and I met her in New York and loved her immediately.

You also cast Bill Murray in a role that, in retrospect, seems like a Bill Murray part, although no one at the time could have known it would be a Bill Murray part. I think you did it again with Anjelica Huston in three movies. Was there any precedent or bit of information that made you think she’d be right for Etheline?

No. Probably I just knew. What we know about her suggests that if there are any living people like the characters in Tenenbaums, she knows them and she’s probably related to them one way or another, you know?

I guess, between having dated Jack Nicholson and having John Huston as her dad. Did she talk to you about that ever during the shoot, about perhaps seeing something in the script that sparked an association with her in her life?

I think it’s probably safe to say Anjelica has known every kind of person you can think of. She’s covered it.

I was not tremendously shocked to see Owen knock the role of Eli Cash out of the park. It seems like almost a fantastic, cartoon version of the public image of Owen Wilson, and the same for Gwyneth Paltrow as Margot. The real surprise for me was Luke Wilson. Although there was an undercurrent of melancholy to some performances he’d given before, I was completely unprepared for the sheer magnitude of suffering and pain he brought to the part of Richie Tenenbaum. And his face — certain titles of your films make me think of one image, and the image I think of for this film is him looking in the mirror after he shaves, just before he tries to kill himself. That’s The Royal Tenenbaums to me — that shot. What was it that made you think he would work in this?

I just thought he would. That part was written for Luke, certainly, and there were several things at play. One is that Luke has always had some people who were his followers. When Luke got sent to boarding school, he was saying that no one there liked him, and his father went to visit him, and maybe I won’t remember this exactly right, but the thrust of it is that when his father got there, Luke was just being elected one of the prefects or something. When Mr. Wilson got there, what he saw was that Luke was one of the most popular kids in the school, that he was kind of a hero in the school — but Luke just didn’t feel that appreciation I guess. He didn’t want to be there. He was sad there, and he was homesick, and he didn’t want to be there. And that kind of combination, that’s very unusual. He’s a very charismatic person, and he certainly doesn’t wear his heart on his sleeve.

He’s walking around like a ghost in this movie. He’s like a ghost in his own life, and I know it’s an ensemble movie, but if I had to say who the movie is about, I think I would say it’s about him.

I always thought of it that way. I mean, Gene does have the showiest character, but Luke’s character is the hero of the movie. Here is the ensemble around him, his family. But he is the center. Not Hackman, but Luke. The thing is, Hackman makes things happen in the story. Royal, I guess you’d call him.

Right, he’s an irresistible force.

And he does things, as a result of which everything’s happening. He’s lying and doing the things that are making the next thing happen.

Right. He’s committing acts that a person should atone for, and then he’s atoning for them.

I like that.

And yet, ultimately, it’s Richie who kind of turns the key in the engine, and that’s when the family — I wouldn’t say they ever quite become healthy, but certainly they’re addressing things they haven’t before and trying to make amends for things that have gone wrong, and I feel like he’s responsible for that.

Does Richie go to Royal or something in the end? In the last part of the story?

Yeah.

He brings him back in, right?

Yeah. I didn’t even realize it until a couple of months ago. I watched it again, and I went, “Oh wow, he’s kind of like Max Fischer in Rushmore. He’s bringing everyone together.”

Richie brings Royal over to see Eli.

And talks some sense into him.

Right, right. He walks in with him and—

Also, he reaches out to Royal after Royal’s been completely cut off from the family.

But do we see him go to him? We only see him with him when they go to Eli, right? Or is there a scene before?

There’s a scene where he goes to see him in the hotel, and they’re riding in the elevator together.

Yes, and the bird comes back.

Yes.

Yes, you’re right.

And there’s the moment up on the roof.

He goes to the hotel, and they’re riding in the elevator. What are they doing there? He’s gone there—I just don’t remember. [Matt laughs] I do remember shooting it, but I don’t remember what happens. I know they’re in the elevator together. He hangs the boar’s head back up on the wall, and then he goes to his father — that’s what happens. Yes, I remember. “Ruby Tuesday.”

That’s right.

I’ve shown I have a rough memory of approximately what might have happened. It was a long time ago, I must say.

I do want to ask about the production design, because this is, I think, a quantum leap over Rushmore in terms of the moving parts. I’m assuming you had a shop that was working 24/7, just making stuff.

One thing that helped was that everybody knew what we meant to do. We hired just enough people, and we did it. I worked with Eric, my brother, before we started the movie, and he drew everything for the house. We had everything kind of done, and I gave the work to David Wasco and Sandy Wasco, the production designers, and they knew — they had a lot of information that wasn’t just my notes; they had pictures of all these things. Eric did very good pictures.

There’s a moment in the opening montage where the narrator’s talking about Margot, and we see her click on a light in her little model theater. I laughed at that the last time I saw it, because you’re really big on cutting away walls, or on shots that seem to have cutaway walls, even if that’s not what you’re looking at.

Shots that require cutaway walls, whether you’re supposed to notice it or not.

Right, right—that idea that you’re Superman, with X-ray vision, and you can see into the building. Did you build a lot of dioramas when you were a kid?

Some, I think, but I used to draw a lot of things in cutaway perspective. I used to draw houses where you could see inside, and boats and things — I’ve always liked those kinds of views. And The Life Aquatic was inspired first by a character — somebody like Jacques Cousteau — but also by an idea about a boat that’s been cut in half. I mean, that was the beginning of the movie, those two things.

You’ve got a lot of shots in all your movies where we seem to be physically moving through walls. In some cases they seem to be sets that were specifically built that way, and in other cases you seem to position the camera in such a way that you’re moving through a doorway and it appears that you’re passing through a wall, or you’re going up or you’re going down a level.

I remember that when we did the opening scene of Bottle Rocket, in the very beginning when he’s in a mental hospital, his bedroom was, in fact, just the end of a long, open room. It wasn’t a little bedroom — we just used three walls of a bigger space. One end of a big room. I remember, at the time, thinking that this is a very good system, which is basically to say, “A set. Interesting.”

And when we did Rushmore, we were supposed to do a scene where they were going to have a ground-breaking for the aquarium, and it was supposed to be on this baseball diamond, and we had all these things organized — and then it rained the night before, and we arrived, and the place was just mud. The field had ceased to be a baseball field. It was a problem. So I sort of came up with, “Let’s not look at the baseball field, then. Let’s look at the dugout and the backstop.” We shot the whole scene in a line, a scene that was meant to be moving all around the place. “We’re going to build a dolly track, and we’re going to go here, here, here, here, and here.”

We did a scene, and I liked how it worked out very much. I’ve now done variations of that shot twenty-five times and followed the train of thought from getting rained off the baseball diamond — it’s this kind of movement that I’ve always liked in movies.

Lateral.

Lateral, but only because, after this one instant of improvisation, I sort of kept doing it. More and more, I’d say, “I’d like to do this on a train track.”

In addition to that shot you mentioned in Bottle Rocket, you’ve got the scene with Miss Cross and Max in Rushmore, where they’re talking and you’re moving across the fish tanks.

Yes, right.

That shot has an element of this in it.

And we weren’t rained out.

But you’re trying to make it look like the “Superman with X-ray vision” effect.

Hmm. Well, it’s through the windows. And aquariums.

And then in The Royal Tenenbaums, you’ve got a lot of those moving-through-walls shots. And I felt like that shot of Margot clicking on the light for that diorama is, or at least has become, in retrospect, almost like a joke about this obsession that you have, you know? It’s almost like making it official.

Hmm. Either a joke or just a part of it.

Yes. And then, since we’re on this: The Life Aquatic. You have the boat chopped in half, and you’re crawling all over that thing. But you also have the action sequence when they’re rescuing the Bond Company Stooge. There are a lot of those types of shots — long lateral shots where the camera’s passing through the architecture. And then I think it reaches its apotheosis in Darjeeling with the train. The train — that’s my favorite.

The sort of “dream train” shot.

The dream train, yeah, because it’s not just violating all the laws of physics—

It’s violating all the laws?

Everything, space and time. There’s nothing real in that shot. It’s completely figurative space.

You’re right. It’s completely figurative everything. And the thing is, it’s meant to be — but to me, the scene is really about “Remember this person?” and “Here’s where this one is,” and “Don’t forget about this one.”

Well, there’s also sadness in commonality. It’s like the idea of death as the great leveler, or the fear of death as the great leveler. That’s rarely been expressed so simply as in that shot and the fact that all the train compartments are rich or poor. It’s like the line from Barry Lyndon: “Rich or poor, they are all equal now.” And then you turn to reveal the tiger in the bushes, which is your grim reaper.

Right. A man-eater.

There are a lot of recurring interests in your movies that get gathered together into that one shot.

I always thought when we were doing it that there was no question that we were going to do it, and we were going to do it in this particular way, and we needed Natalie Portman here, and we needed Bill Murray here, and whether four thousand, six thousand, or twelve thousand miles away — I don’t know how many miles — we had to do it this way, we had to get everybody on this train, and we were going to do it this way. But I did always think, “I have no idea what this is going to—”

Wait a minute. That was on an actual train? I assumed that was a rear projection.

No, that was—

You built this set on an actual train? All the different rooms? And the countryside that we see going by in the background is the actual thing?

Yes, that’s the real countryside. It was very exciting to do.

When you turn to reveal the tiger, what is that, the other side of the train?

No, it’s all one car. We gutted a car, and that is a fake forest that we built on the train, and it is a Jim Henson creature on our train car. The whole thing is one take, and I think because we did it that way, while we were doing it, we did feel this electricity, you know? There’s tension in it because it’s all real. Fake but real. I mean, that was the idea. The emotion of it, well — there’s nothing really happening in the scene, you know? They just kind of sit there, but it was a real thing that was happening. But I did at the time have this feeling like “I don’t know.”

Well, it’s also similar to that great near-ending shot of I Vitelloni, where he’s leaving the town. But it’s almost like an inversion of that shot, where you’re seeing the camera passing through the rooms as if we’re on the train, but this time it’s like you turned it inside out in some way.

It’s very beautiful, that I Vitelloni one, and there’s another one in The River. Do you know it?

Yes.

A very similar thing.

Which brings us back around to our conversation about Bottle Rocket: Rear Window. Rear Window — what are we looking at? A series of people in these little boxes, and they’re like animals in a zoo or creatures in a diorama, a butterfly collection.

Right.

And here you are, you’re the viewer, you’re looking. You can see through walls. It’s kind of beautiful how it dovetails with so many of the concerns in The Royal Tenenbaums, chief among which is the sense that the world is looking at the Royal Tenenbaums, at us, that the eyes of the public—whoever that is—are constantly upon us, burdening us with their expectations, you know?

Right. Which we can only manage to disappoint.

Excerpted from The Wes Anderson Collection by Matt Zoller Seitz, from Abrams Books.

* George Drakoulias is a record producer and music supervisor who got started as an A&R man for Rick Rubin’s Def Jam label, later Def American. The character played by Michael Gambon in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou is named Oseary Drakoulias, a splice of Drakoulias and Guy Oseary, Madonna’s manager, the founder of Maverick Records, and an executive producer on the Twilight films. Drakoulias also inspired Billy Bob Thornton’s character “Big Bad George Drakoulious” in Dead Man and the Darkoulias monster in the 2009 Star Trek, and you hear his name in a lyric of the song “Stop That Train” in the B-Boy Bouillabaisse section of the Beastie Boys’ album Paul’s Boutique: “Went from the station to Orange Julius, I bought a hot dog from who? George Drakoulias.”

** The Gare d’Orsay, a turn-of-the-century railway station on the left bank of the Seine in Paris, later became the Musee d’Orsay, home to the world’s largest collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist masterworks.