There’s never been a more frustrating time to be a socially progressive fan of Marvel Comics. Not because its many titles are conservative or hateful — just the opposite, in fact. Marvel’s printed superhero books are more ethnically diverse, feminist, and queer-positive than they’ve ever been. The frustration comes because, even as Marvel’s printed offerings are looking forward, its popular live-action movies and TV shows feel like relics from a lily-white, male-dominated, straights-only past. It’s time for Marvel to push its onscreen output into the 21st century by learning from its own source material.

In the past two years, Marvel readers have been treated to stories that push the boundaries of what superheroes can look like. The most visible examples of that trend have, not surprisingly, come in the franchise that has, historically, been Marvel’s cash cow: the X-Men books. The franchise’s two flagship titles — All-New X-Men and Uncanny X-Men, both written by longtime comics scribe Brian Michael Bendis — have been exceptionally open-minded. At the center of both books is an explosive development: the introduction of a group of newly discovered mutants, the majority of them women or people of color. None are stereotypes, either — the Latino and black kids aren’t gangbangers who talk in slang, the female character isn’t whiny and vain, and so on; they’re just teenagers, figuring out their weird new situations. And speaking of female characters, the X-books these days practically make Girls look like a sausage fest. Indeed, in a cheeky bit of ironic titling, the series called X-Men was recently relaunched with an all-female cast of six X-characters — half of whom happen to be women of color. Nearly every issue of the main X-books passes the Bechdel Test, like, four times over. Oh, and there was that big same-sex wedding the X-Men had last year.

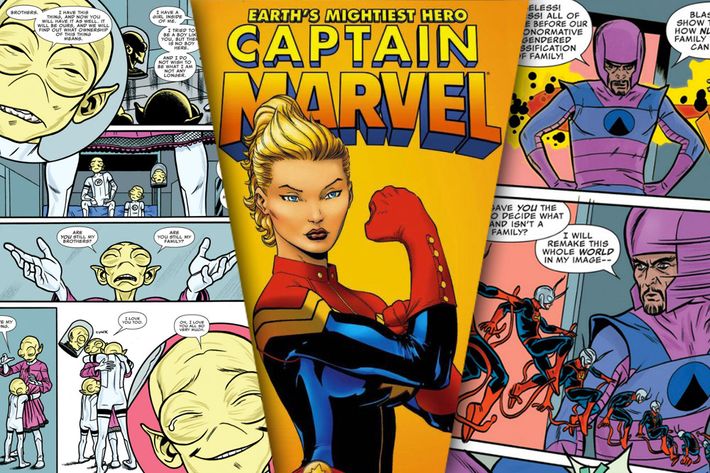

The tide is rising elsewhere at Marvel, too. One of the two current Fantastic Four series, FF, stars an emergency backup team (because the main team is currently displaced in time for reasons that are too bonkers to summarize), 75 percent of whom are women. And FF just revealed that one of its characters is transgender — but instead of being some overblown event, it’s just something the cast acknowledges as being totally okay before going on with their world-saving. In Ultimate Spider-Man, the new Spider-Man (Peter Parker having died a little while back) is a super-smart, half-black, half-Latino teenager with an Asian-American best friend and female quasi-sidekick. The long-running Captain Marvel franchise was just relaunched with a female Captain Marvel. Roughly half of the Avengers are either women or people of color. I could go on, but you get the picture.

But if you’re an average superhero fan — the sort who knows specifics about Marvel’s superheroes mainly through the successful film franchises — you would have no idea any of this was happening. In fact, based on the content of Marvel Entertainment’s massively profitable film and TV empire, you’d almost think Marvel’s creative directors worked for a conservative think tank. Take, for example, the recently debuted (and cumbersomely titled) ABC series Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. It follows a black-ops team that’s primarily white (with the exception of Ming-Na Wen and half-Chinese-half-Caucasian Chloe Bennet*). Through its first two episodes, the only black character with more than two minutes of screen time was an angry villain: an unemployed, black single parent, addicted to druglike technology, who kidnapped and manhandled a white woman. The second episode took our heroes to Peru, where the only person of color they really interacted with was a sexy Latina villainess.

None of that should come as a surprise, given that the show is a spinoff from the so-called Marvel Cinematic Universe (or MCU, as it’s known among fans). The MCU is just about as non-inclusive as superhero universes can get. Here’s the breakdown of the superheroes who aren’t white men in the MCU (which includes the Avengers, Iron Man, Captain America, and Thor films — Marvel has no direct control over the X-Men or Spider-Man film franchises, which are owned by Fox and Sony, respectively.): one white woman (the Black Widow, who of course fights in a skin-tight catsuit and regularly uses her sexual wiles to thwart bad guys) and two black men (Nick Fury and James Rhodes). There have only been a handful of other women in the various MCU films — all white, and all in damsel-in-distress roles.

The next MCU flick is November’s Thor: The Dark World, which stars a blonde Nordic god and will feature only two black characters, one of whom is a hideous bad guy. (In Marvel’s defense, they cast Idris Elba as a heroic Norse god in Thor, prompting some outrage from a white supremacist group.) After that will come Guardians of the Galaxy, similarly featuring black and Latino baddies against a white male hero (Chris Pratt’s Star Lord). Marvel movies are planned out well into the latter part of this decade — not a single one about a female superhero. Defenders of the MCU will point to this or that little bit of diversity, but it’s all slim pickings. Marvel flicks will continue to be a boys’ clubhouse where girls get occasional guest passes.

What’s going on here? Why this insane dichotomy between Marvel’s comics and its live-action stuff? The reasons are maddeningly obvious and time-worn: Big-budget action movies and shows — be they spandex-clad or not — simply don’t get made without straight, male, (usually) white protagonists. It’s all supposed to appeal to the imagined median viewer: a hetero Caucasian (or Chinese, given Hollywood’s increasingly global marketing focus) dude.

But here’s the thing: Those same arguments were held as truisms in superhero comics for decades. Marvel and DC clung to the ideas that franchises couldn’t risk more than the occasional token black guy and that lady heroes have to wear impractically sexy outfits. But now Marvel Entertainment — led by former writer-artist Joe Quesada — obviously doesn’t hold to that. Its printed output is living proof. Quesada and his creators took a leap of faith by making their comics radically more inclusive, and it has paid off — the X-books rake it in monthly. What’s more, the lesser-selling books mentioned in this article — FF and Ultimate Spider-Man, for example — haven’t been canceled by Marvel, which means the higher-ups believe these stories and characters are worthwhile, even if they have to take a loss on it for the time being.

The financial stakes are much higher for multi-billion-dollar movies and shows, of course. But so are the philosophical stakes. Marvel currently has the eyeballs of hundreds of millions of moviegoers across the globe — something that’s never been true before for any comics company. It has a massive platform to tell all those viewers across the planet, “Anyone can be a hero, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, or anything else.” It’s not as if Marvel hasn’t tried and succeeded wildly in getting that very message across in the past.

* This post has been corrected to note that Chloe Bennet is half Chinese.