The meet-uncute of Nikki Finke, scourge of Hollywood, and Jay Penske, automotive scion, happened through the matchmaking services of mutual friend A. Scott Berg, the Pulitzer-winning biographer whose brother Jeff is a powerful Hollywood agent. Finke had interviewed Berg, and Berg had written about Penske. This was in 2008, when Finke’s entertainment-news blog Deadline had become an essential, compulsive read in Hollywood, drawing impressive web traffic. Over a two-year period, Finke says, some 25 potential buyers, reportedly including Variety owner Reed Elsevier, the Huffington Post, IFC, and the billionaire Haim Saban, began “kicking the tires.” Berg and another intermediary, Dani Janssen, the host of a prominent Oscars party, reached out to Finke to tell her that Penske was interested, too. “Scott said, ‘He’s the real thing,’ ” Finke remembers.

Finke was reluctant to sell to anyone, but her father, stricken with bladder cancer, urged her to seize the moment: It might pass, and here was a chance to become financially secure. He died in January 2009, and Finke spent the next six months negotiating with Penske. She was impressed by his knowledge of the Internet, by what she calls “one of the most agile, bright, and articulate minds I’ve encountered,” and by what seemed like their shared vision for how to grow the site. “He was relentless,” Finke says. “We fought like cats and dogs during the negotiations. I cried. I got mad at him. I called it off at least a few times. It was always, ‘I don’t want a boss. I love being my own boss.’ ” Finke warned Penske she’d be “the worst employee you’ll ever have.”

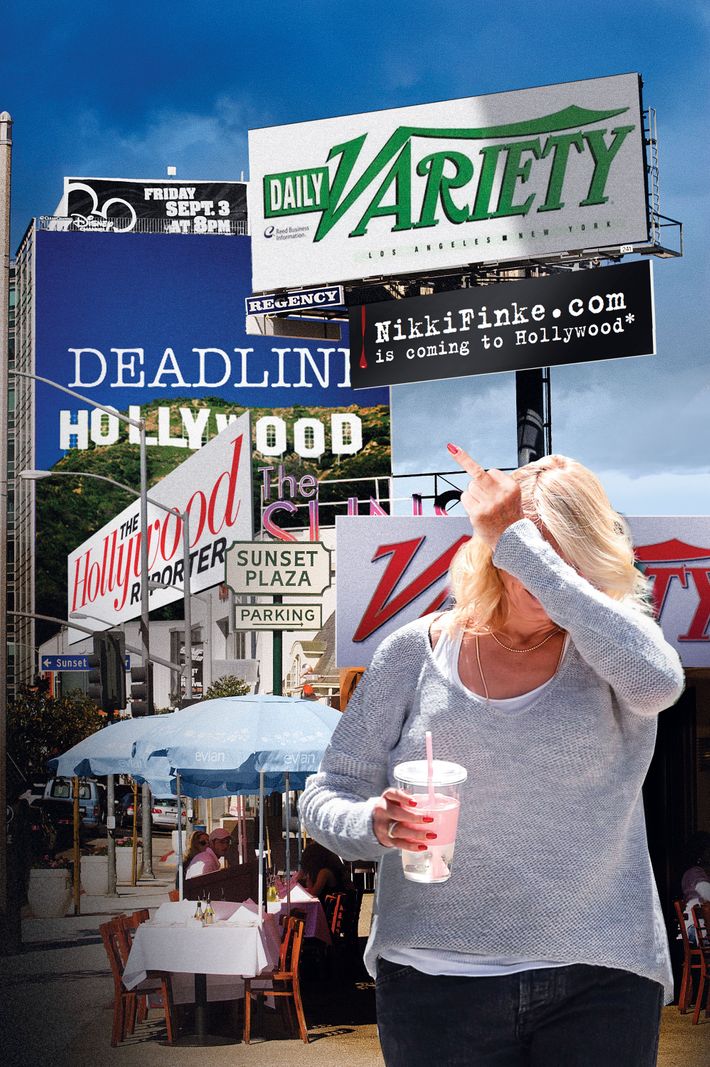

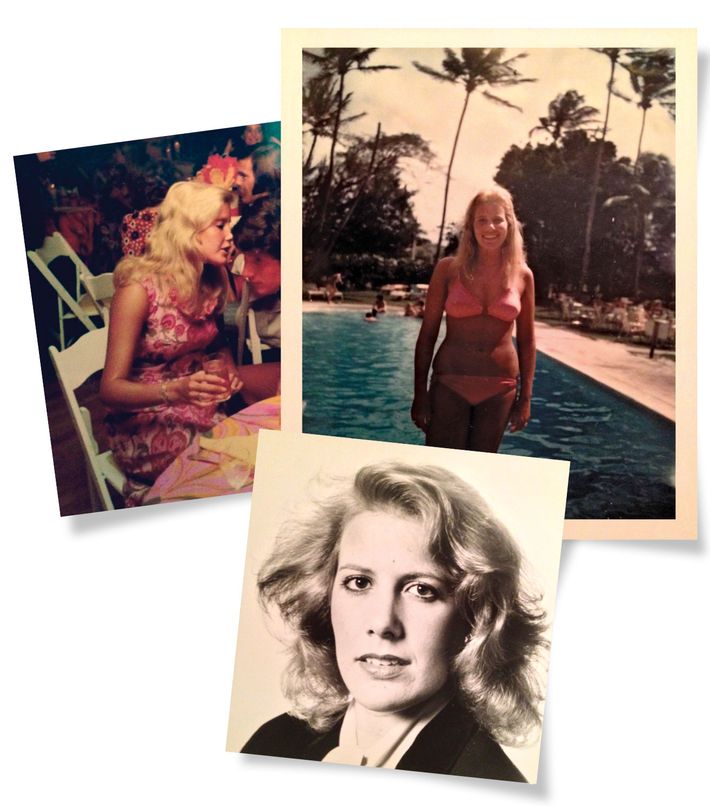

Coming from Finke, who turns 60 next month, this was not hyperbole. The news she surfaced aside, what made Deadline a thrilling, guilty pleasure was her savage keyboard persona—the banner headlines screaming “SHOCKER!” and “TOLDJA!,” the invitation to antagonists to “stick this up your asses” and “get the fuck out of my face,” the takedowns of studio executives so vicious they sent the cowed victims scurrying to Internet-reputation companies to have the stories buried on Google. Her behind-the-scenes tactics were no less brutal: She would threaten people to get them to cooperate with her, punish those who helped her competitors, and exact revenge on anyone she perceived as having wronged her. Hollywood lived in fear of Finke and was all the more intrigued because of her Thomas Pynchon act: Only a couple of photos of her existed on the Internet, and no one had seen her at an industry event in years.

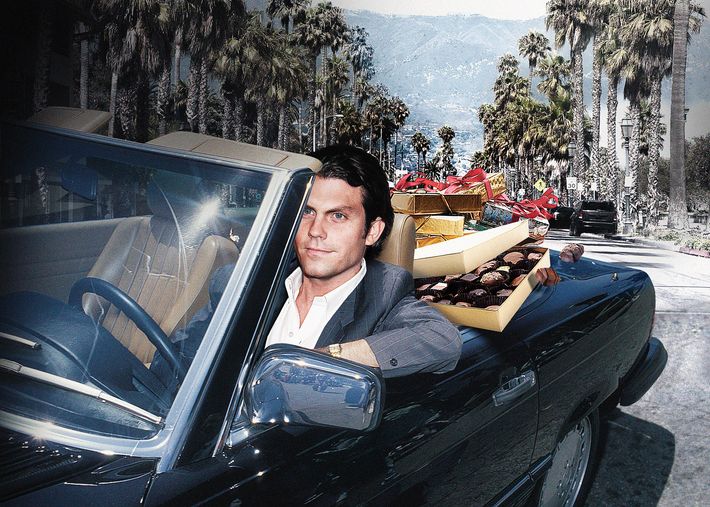

Penske, the youngest son of Detroit billionaire Roger Penske, wasn’t an obvious match. He had started out in business making a cell phone for children that had parental controls. Now 34, he is handsome, with blue eyes and product-gleamed hair, and has dated actresses like Devon Aoki, Gina Gershon, and Lara Flynn Boyle, who got a shoulder tattoo of a jaybird (from her nickname for him); last year, he married Elaine Irwin, the former Victoria’s Secret model, with whom he has a baby. When not on a plane, where he spends much of his time seeing to his far-flung business and extracurricular interests, Penske is chauffeured around L.A. in his gray Aston Martin DB9 by a driver named Raoul. He owns an IndyCar team, Dragon Racing, and an antiquarian bookstore in Los Angeles, Dragon Books. (The dragon thing: The first book he loved was John Gardner’s Dragon, Dragon.) He seems to share some of Finke’s privacy concerns: Behind the desk in his office in Inglewood is a bank of surveillance screens, and despite running a media company, he rarely speaks on the record to the press; he met with me at Variety’s offices only on the condition that I not quote him. He has told people that he has never taken a penny from his father, but depending on whom you ask, he is either an entrepreneurial Renaissance man or a dilettantish bro with a rich dad. Before attending Wharton, he was kicked out of a series of prep schools and was a star lacrosse player. Last year, he and his brother Mark were arrested at the Nantucket Yacht Club for trespassing and urinating on a woman’s feet. (The Penskes were sentenced to a year of probation.)

When Penske started discussions with Finke, he was in the process of building a collection of websites, many based around personal brands. They came to terms in the summer of 2009—he bought Deadline for an amount that would ultimately pay out a minimum of $14 million. This made Finke rich. (In 1982, she had walked away from a brief marriage to Jeffrey Greenberg, the son of AIG CEO Hank, with just enough to pay back her parents for the wedding; her father left her a “decent” inheritance, but “there’s decent, and then there’s decent.”) Penske, for his part, got attention, appearing on the front page of the New York Times and making Vanity Fair’s “Next Establishment” list. With Penske’s resources, the site’s staff grew, and Deadline’s web traffic surpassed the combined traffic of The Hollywood Reporter’s and Variety’s websites.

For a time, the odd-couple partnership worked out better than expected. Penske found his thuggish new investment amusing and took to calling her “the Don.” Finke: “He calls me three or four months ago, says, ‘I had a dream about you last night. I was at your memorial service; it was my turn to speak.’ I say, ‘Wait, was I dead?’ ‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘It was my turn to speak, and I don’t know what to say, so I repeat all the things you’ve called me over the years.’ ‘Snake-oil salesman?’ ‘Yep.’ ‘Con artist?’ ‘Yep.’ ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy?’ ‘Yep.’ We both started laughing. I said, ‘At least you were accurate.’ ” He insisted that she should live somewhere better and said he’d buy her an apartment; she found a condo in West Hollywood, which he ended up renting to her. The day he got in trouble in Nantucket, he called her repeatedly to vent about the media frenzy. “I felt awful for him,” Finke says. “I was flattered he turned to me. It drew us closer.” But Penske may not have reckoned just how high-maintenance Finke could be. “He didn’t have to come up the corporate ladder,” says a former colleague from Penske’s company, PMC. “He’s used to being catered to. He’s not used to having to eat shit. Now all of a sudden it’s I’m beholden to Nikki Finke, who wants me to eat her shit.”

When Penske decided in 2010 to put out special awards-season Deadline print editions, Finke bristled at the extra work, citing health problems (she is an insulin-dependent diabetic). In February 2011, after Finke’s lawyer accused Penske of violating her contract, two LAPD officers showed up at her door saying 911 had received a call that she might be intending to harm herself; Finke was perplexed, until they told her that one of Penske’s executives had placed the call. (At the insistence of Finke’s lawyer, the executive later wrote an apology to the police for inconveniencing them: “The seriousness of the situation might have been overstated.”) Then, on a Sunday night in May, after Penske had, according to Finke, withheld some ad-commission money owed to her, he personally delivered a care package. Penske somehow got into Finke’s building without being buzzed in, and suddenly, shortly after 11 p.m., appeared outside her door. “I was so mad that I would not open my door,” she says. “I was furious, so furious at my privacy being violated.” Finke says that for fifteen minutes Penske “kept yelling my name and banging on the door, loud enough to wake the entire building. He kept saying, ‘I want to come in, I want to talk.’ ” Finke threatened to call the police. “Eventually he leaves. I see this package. I’m curious. I open it up. There’s the check for the money he owed me. And there is like a little medley of Beverly Hills Hotel desserts.”

Finke threw them in the trash and fired off an e-mail to PMC’s HR person, complaining that the visit constituted stalking and that the food could have seriously harmed her.

“Who does this to a diabetic?” Finke says now, quasi fuming.

In June, the co-dependency was revealed to have curdled into something worse when Sharon Waxman ran a post on her rival site, the Wrap, headlined “SHOCKER,” which claimed Penske had kicked Finke to the curb. It was false, but reflected a truth: For the past year, Finke and Penske have been on a collision course, and the Nikki Finke–Jay Penske show, live on multiple platforms, including Twitter and Deadline, has become one of the more compelling unscripted entertainments in Hollywood. See, for instance, Finke’s retweet of @ZacharySire’s “Is Penske the CEO of a multimillion dollar company or a high school girl?” Earlier this month, Waxman’s scoop became belatedly true, sort of, when Deadline suddenly announced: “Deadline.com and Nikki Finke Parting Ways.” Or, as Waxman couldn’t resist putting it, on the Wrap: “TOLDJA!”

Though Penske disagrees and is pursuing binding arbitration on the subject, Finke adamantly believes she is now free to reboot her career, independently, and pick up where she left off before the Penske drama consumed her. Then, way back in 2009, Finke loomed over Hollywood as a groundbreaking historical figure, a disrupter who’d changed how the entertainment business talked to itself. Her own story was kind of inspirational (a David to the Goliath duopoly of Variety and The Hollywood Reporter), kind of idealistic (a truth-teller among the hacks), and kind of horrific (she could be mercilessly cruel, and has idiosyncratic ethics).

Earning Finke high reviews among those who read her religiously: She got some big scoops, like executive firings before the executives knew, and the impending merger of William Morris and Endeavor. During the 2007 Writers Guild strike, Deadline served as an essential counterweight for the writers, while the old trades carried water for the studios. Her “live-snarking” of the Oscars could be hilarious. And on a regular basis Deadline’s comments section gave anonymous cover to Hollywood’s little people. “It was a huge game-changer in our business,” says a leading agency executive. “I don’t want to overstate it, but I feel like it affected how people behave. If you’re a real dick, the comments section will go crazy when that name is mentioned.”

Less well received: Finke’s irony-free style of self-promotion; her shakedown tactics, including extending protection to favored sources; her insouciant revisionism, like when she’d change posts after the fact without acknowledging she’d done so.

Then there were the mutilated bodies, which got mixed reviews, depending on how you felt about the victims. There was Marc Shmuger, news of whose imminent firing as Universal Pictures co-chairman Finke broke in a long post that called him “a polarizing asshole” and “thin-skinned crybaby” who’d been “embarrassing himself.” Ben Silverman, when he headed up NBC’s entertainment division, was “an incredible pussy” who was “prone to flop sweat” and had a “record of abject failure.” Of Silverman’s boss at NBC, Jeff Zucker—a “thin-skinned humorless bully” and “overpaid blowhard”—Finke delighted in reporting that the “putz” had “cried” during his final days at the company. All of this added up to a character Hollywood couldn’t resist. HBO put a half-hour sitcom based on her, Tilda, into development. (The pilot, starring Diane Keaton, wasn’t picked up.)

Key to Finke’s mystique is her peculiar brand of reclusiveness. Considering her fearsome reputation, she is unexpectedly engaging, by turns serious and funny, and readily accessible by phone. Over the past few months, we spoke more than a dozen times. Calls with Finke often ran two hours, and usually I was the one who brought the conversation to a close. She is fond of the rhetorical question—“Can we deal in reality, please?”—and of landing her sentences with high-pitched overstatement, wherein various things are CRAZY or NUTS or UNBELIEVABLE or HILARIOUS (if there is a way to communicate block caps using sound, Finke has found it). She was selectively transparent, disclosing seemingly revealing things about her health (“I was wandering around the Mayo Clinic for three weeks”), her early childhood growing up on Long Island’s North Shore (“I had no friends; I had books”), and her money (“Twice a day I call up all my accounts and look at them lovingly; I love looking at my money”). Finke’s attention would take sudden swerves. One minute she’d be talking about some mogul’s duplicity, the next she’d be free-associating about an image of Michael Bay (“Making himself look like some kind of Norse god … make me puke”), a TV news report of a shark attack (“Holy shit, the sharks are turning on the humans”), or her thirst (“Hang on a second, I want to pour myself some iced tea”). And she wanted to set the record straight about something: “People think I have 25 cats. I have no cats.” The one she used to own, Blue, now lives with a couple in Santa Maria, California, “near Driscoll strawberry fields. That is not a euphemism for Heaven. I get regular photos of him.”

Finke also choked up a few times, like when speaking of her father’s death or about her difficult relationship with her mother. She told me a story about how, when she boarded at Miss Hewitt’s Classes, the girls’ prep school on East 75th Street, the housemother called her into her office one day and asked what went through her mind when she took a shower. “Do you realize,” the woman said, “that every time you take a shower, you weep?” Nikki pooh-poohed the idea, but the woman said: “We have to get to the root of why you do this, what is so painful that you can’t even face it.” As Finke recounted this story to me, she began sobbing, then said, “She diagnosed that it was my family and my mother, and she forbade my mother from talking to me during the week, and I slowly stopped crying.”

Finke says she has mellowed, and professes to be self-aware, and there was some evidence, in our conversations, to support this. “When you’re a control freak, you want to control everything, and there’s a point where you can’t,” she said. Of her reputation as a bully, she said: “Eighty percent of the time, when I’m mad at someone in Hollywood, it’s because they treated my staff horribly. Ten percent of the time, I’m not asking for special treatment, I just want equal treatment. And then 10 percent is, I had a bad day, my blood sugars are out of whack, I’ve worked all night, I’m tired, and I’m an asshole. And what people don’t realize is I’ll apologize. I know when I’ve been an asshole.”

And yet, though loquacious on the phone, Finke is exceedingly guarded about her physical privacy and public image. PMC’s employment contracts include a clause per which the undersigned agrees to keep confidential “any information relating to Nikki Finke, her persona, likeness, and any and all personal and business activities.” Most of Finke’s employees have never met her, though Nellie Andreeva, her TV reporter, insisted on a face-to-face meeting, had dinner with Finke at a restaurant, and is said to have told people afterward that “she’s not like what you think she’d look like; she’s very normal-looking.”

Finke says she spent five months in Hawaii this year and two weeks in Europe. She also claims that while she doesn’t do lunch at the Ivy or take meetings at the studios, moguls, agents, and executives come to her home office “all the time.” (Not a single person I spoke to at a studio or agency had ever been to Finke’s home office or even heard of anyone else’s going there.)

In any case, Finke has her reasons. She’s shy. Her parents were private people, speaking French in public to thwart eavesdropping. She gets claustrophobic when she’s around a lot of people. She has been cyberstalked. She needs to conserve energy. But it’s also clear that she has benefited from her enigmatic aura. “All of that is a frickin’ playbook right out of Hollywood, by the way,” says a prominent industry publicist. “We invented mystery, and we know the power of it and the importance of holding on to it.”

This power was threatened in October 2009, when Gawker offered a $1,000 bounty for a new photo of Finke. Around that time, a young reporter at the Wrap named Hunter Walker half-seriously proposed staking out Finke, and one day, after Finke had bullied various executives planning to appear at a conference Waxman was hosting, an exercised Waxman made the assignment. She knew where Finke lived. “It was a crappy condo in Westwood,” Walker recalls.

Walker began his stakeout, but the Wrap aborted the mission the next day. Walker recommenced his surveillance later, when he left the Wrap to work for Rupert Murdoch’s Daily. He’d arrive at Casa Finke at 6 a.m., park across the street, and keep his eyes on Finke’s building until 10 p.m. After four days, a professional paparazzo took over, and a few days later he got the picture.

The photo that ran in the Daily, under the heavily lawyered headline “Is This the Most Powerful Woman in Hollywood?,” showed an attractive, scowling blonde woman behind the wheel of a car with her hand raised as if to block the picture. Finke flat-out denied that it was her. Two people who’d known Finke for years, blogger Anne Thompson and Waxman, both publicly insisted it wasn’t her. But the Daily team was almost certain they had their woman. Richard Johnson, the Daily’s gossip editor, called Finke to tell her they had her picture and had a two-hour phone conversation in which he offered to show her the picture himself to verify it. Finke rejected the deal, instead offering, Walker says, “to give us unspecified scoops she claimed were massive, in exchange for our agreeing not to print the photo.”

When Waxman was the New York Times’ Hollywood correspondent, she and Finke were friends. Waxman would have Finke over for Shabbat dinner. After Finke’s mother died, Finke gave Waxman two of her chairs. Finke says she helped Waxman write book proposals and, after she left the Times, supported her expressed interest in starting a politics website. Then Finke started hearing that Waxman was in fact planning to launch a rival entertainment-business-news site and had “told everyone she was going to put Nikki Finke out of business.” Finke says she called Waxman and confronted her. “I said, ‘I’ve helped you. You know I have had a struggle. Why?’ Her answer was: ‘I tried to do something else, and I can’t get work unless I do Hollywood.’ I said, ‘Look, if that’s your definition of friendship, you’re no longer my friend.’ I can’t stand people who lie to me. That was it.”

Waxman launched the Wrap in 2009, backed by Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz. Though it has yet to attract enough traffic or clout to challenge Deadline, it has enjoyed dazzling success as a pebble in Finke’s shoe. Finke, for a time, would write disparaging items about the Wrap without using its name, referring to it only as “a blog.” Later, she switched to referring to it always as “the Crap.” She accused it of stealing scoops, repeatedly mentioned its high staff turnover, and invariably qualified any reference to Waxman with an adjective like “desperate,” “clueless,” or “error-prone.” Waxman, for her part, has run items with headlines that start “Hey, Nikki” or “Memo to Nikki” (as in, “Memo to Nikki: Stop Saying the Wrap Isn’t Breaking Stories”). She’s hurled insults over Twitter with the hashtag #pathetic.

Of more concern to Finke, and certainly to Penske, has been the rehabilitation of The Hollywood Reporter, which was purchased in 2010 by a private-equity group that included Guggenheim Partners, and which installed the former Condé Nast executive Richard Beckman as CEO. Now edited by Janice Min, formerly of Us Weekly, the magazine has been transformed into a glossy weekly that does a very good job glamorizing the less sexy parts of Hollywood. Min also redirected the website toward breaking news, so it now competes directly with Deadline for scoops. This year, The Hollywood Reporter became the media sponsor of the prominent “Night Before” Oscars party, which had for years been a Variety event.

All of this seemed to unnerve Penske, who is as competitive as Finke—and who suddenly found the brand he’d bought displaced in Hollywood’s imagination. According to a former PMC executive, Penske became “obsessed” with The Hollywood Reporter, poring over every new issue. He sent out cease-and-desist letters to the magazine, accusing it of poaching Deadline employees and recycling its content, and ultimately sued THR’s owners, claiming copyright infringement. When word spread in fall 2011 that THR’s archrival Variety might be in play, he asked Finke whether he should buy it. She was encouraging.

Finke says that they strategized about how Variety should be run and that, while she never expected to be its editor, she did believe she’d have a hand in its overhaul. She thought there might be synergies, with staff who worked for both Deadline and Variety and regular meetings to make sure the publications weren’t overlapping. In December 2011, Penske got Finke to sign an addendum to her contract. At the same time, without her asking, he gave her the enhanced title of editorial adviser to PMC. She took this as confirmation that she’d have some kind of oversight of Variety. “It was always ‘we’ … ‘When “we” take over Variety.’ ” When it finally went on the block in the spring, Finke says she advised Penske on how to game the bidding by telling friendly reporters the other bidders were overpaying for it, in order to scare them off. Soon after a Los Angeles Times article to this effect was published, Ron Burkle dropped out.

She was incensed, then, when she learned that Penske had succeeded in buying Variety for $25 million, in October 2012, by reading about it in the L.A. Times. “We never even got a press release,” Finke says. “We’re looking around, going, ‘What the fuck is this?’ ” The L.A. Times story also said that Finke would have nothing to do with running Variety, and at a town hall with Variety’s staff that afternoon, the first slide Penske put up said: “Nikki Finke will have nothing to do with Variety.” “I’m hearing this secondhand,” Finke says. “I’m like, what?” A Deadline reporter detailed to cover the meeting was expelled by security. Finke couldn’t get Penske on the phone over the next several weeks, and then she learned that a number of PMC executives would be moving into Variety’s headquarters. Finke says Penske promised to reassign five Variety staff to Deadline, but that this kept not happening, until finally, in mid-December, he said she wouldn’t get them. Finke dates the start of her real unhappiness with Penske to that moment. “We were gobsmacked. He wouldn’t give us a reason. We were waiting for the cavalry.”

Finke went into the hospital two days later, “sick as a dog.” Her doctors told her she needed to work fewer hours, to take vacations. She says that when she told Penske this, she received a lawyer letter stating that under her contract she was required to be working. The indignities, as Finke saw them, kept coming. In February, she heard that Penske was going to hire Claudia Eller, a respected L.A. Times editor, to edit Variety, but when Finke asked Penske about it, she claims he lied to her. “That was the nadir.” She refused to take down a Deadline post about how he’d lied, and she said he owed her the entire remaining value of her contract. He fired her. He un-fired her. This was their relationship.

In March, Variety relaunched as a weekly, and its website dropped its paywall. Penske told people that the reenergized trade magazine was going to be “The Economist of Hollywood.” It’s still a duller read than The Hollywood Reporter (“Hollywood doesn’t read The Economist,” says one industry publicist), but as Variety increasingly became Penske’s focus, Finke’s aggression turned inward, and she became consumed with her own role at PMC. “I really think in some weird, warped way, Jay likes to pretend that he’s in my corner, but what he really is, is he feels in competition with me,” Finke says. “He’s never going to give Deadline what it wants, because he’s never going to get credit for it.”

It’s a plausible theory. But it’s also possible that Penske bought Variety as a hedge. The arrival of Min—and the free-spending money behind her—has redrawn the landscape in which Finke built her power, and it’s an open question whether she’ll ever be as feared or powerful as she was when Penske bought Deadline.

For one thing, people are no longer afraid to ask that question. Last June, the novelist Bret Easton Ellis casually tweeted that he’d learned he lives in the same building as Finke. What followed, according to multiple reports, was a classic Nikki Finke psychodrama. First, she called the office of Ellis’s literary agent, Amanda “Binky” Urban, and gave Urban’s assistant an “epic, otherworldly screaming-at” (New York Observer), later demanding that ICM fire her. Finke also, according to these reports, told prominent West Coast ICM agents that Deadline would print various damaging (and, they said, false) things about them and would also reveal their addresses and where their children went to school. At that point, ICM hired top litigators. Finke: “Anything ICM says about this is so colored by the fact that they hate me because I have reported the truth about their internal shake-ups.” She claims, to this day, not to know whether Ellis lives in her building, though Ellis finds this ridiculous: “I don’t know how she would think that I might not live in her building. I was called in by building management and asked to sign something, as were all members of the staff of the building.”

What’s not classic is the blunt assertion Ellis made in a tweet, mid-brawl: “Anyone in the movie industry who fears they have to ‘watch out’ for Nikki Finke is a complete and total old-school fucking Hollywood loser.” This was new. The idea that Finke, far from having to be feared, might not even matter was seconded two weeks later, when producer Gavin Polone, in a post on this magazine’s website headlined “Apocalypse Nikki,” suggested there was little evidence that Finke had any real power and publicly challenged Hollywood to ignore her.

While Finke resented Polone’s post, she agreed with him in one sense. “Being powerful in Hollywood was everyone else’s characterization of me. It was never mine. I only cared about telling the unvarnished truth about Hollywood.”

Since the wrap’s false-alarm “SHOCKER” story—a popular view in Hollywood is that Finke herself planted it; “I would never plant anything with Sharon Waxman,” Finke says—some of Finke v. Penske has played out in private, some of it all too publicly. On Deadline, Finke repeatedly took aim at hedge-funder Daniel Loeb, calling him “the most hated man in Hollywood,” and Loeb, an investor in Variety with Penske, pressed him on three occasions to fire her, according to a recent report.

Finke was so down on Penske that he could do no right. She was even pissed when Penske and Mike Fleming Jr., a veteran Hollywood trade reporter whom Finke had hired away from Variety, both defended her publicly against Waxman’s post. (“It was sweet, but he’s not supposed to talk about my contract or my relationship with Penske.”) She was pissed, too, when Penske hired Stacey Farish from the Wrap as PMC publisher. (“We had a policy not to hire anyone from the Crap.”)

Finally, Finke, who’d banked nineteen weeks of vacation, decided to take one and headed to Hawaii. Even from her vacation redoubt, the shrapnel continued to fly. Letters flew between lawyers. Grievances were aired in the press. There were internal-control skirmishes at Deadline.

The endgame began on October 23, when Finke received an eight-page letter from Penske’s lawyers that was by turns accusatory and conciliatory. Penske called her several times that day, “begging to work out a settlement with me,” Finke claims. “He likes to call me at eleven, twelve, one in the morning. I resent it. He then falls asleep in the conversation. You go, ‘Jay, are you there?’ You hear this soft breathing.”

In the evening, they spoke by phone. Penske said he thought they could work things out, and after two hours they agreed to continue their conversation the next day. Before that could happen, Finke awoke on Thursday to learn that Penske had rerouted Deadline’s Twitter feed away from Finke’s much more popular feed, saying Finke had “too many followers.”

That night, Finke tweeted: “I am building out NikkiFinke.com and will unveil it right after the new year. Can’t wait to report the real truth about Hollywood.” When I spoke to Finke by phone later that evening, she said Penske had threatened to “rain nuclear war on me if I left.” She said she was dancing around the house to Taylor Swift’s “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” which she also played into Penske’s cell-phone voice-mail.

The next morning, her tweets resumed: “Penske keeps sending me legal letters since I began giving interviews. Latest one this am demands I remove and retract my tweets.” On Friday: “Earth to Penske: Hollywood tried and failed to intimidate me. Big Media tried and failed to intimidate me. I like to brawl, remember?”

When Finke tried that day to post an exclusive to Deadline about a former WB executive, she found that it was shunted to the site’s trash file. She then put up a post on the site—“NIKKI FINKE LOCKED OUT OF DEADLINE”—which was seemingly self-refuting but was true in a sense: She’d lost her administrator access. The post ended with “what an extremely sad day.” Sad, in Finke’s world, can quickly flip into devilish, and within hours, she was retweeting @MassholeRob’s “So glad @NikkiFinke got her balls back. They weren’t doing anyone any good rattling around in Jay Penske’s manpurse.”

At this point, the lines between Penske and Finke were clearly drawn. He believed he had her locked into an ironclad contract that required her to work for him through 2016. She wanted out, and believed the contract was no longer valid. Her lawyer and Penske’s agreed to enter mediation with a retired judge the following week. When Finke and Penske showed up for the mediation around 8:30 a.m. that Monday, they were put in separate rooms while the judge shuttled back and forth between their lawyers. By late afternoon, the mediation broke up, with no resolution reached.

In the four and a half years they’d been business partners, and friends of a sort, Penske and Finke had never met in person, even during the pre-sale courtship. On this day of mediation, though, when they left around 5 p.m., there was a mix-up, and Finke and Penske exited the building at the same time. Suddenly, they found themselves face-to-face for the first time.

“It was very uncomfortable,” Finke says.

It’s been about a month since then. There’s been movement, or maybe not. Deadline’s report that Finke was leaving provided a moment of clarity, but this soon dissolved in a fog of contract conflict—in particular, over whether Finke is subject to noncompete restrictions. Then came Peske’s announcement last week that he would be taking her to arbitration.

It’s unclear what happens to a Finke-less Deadline. Some of the writers Finke hired have dabbled with mimicking her operatic tabloidese (Fleming’s anti-Waxman post over the summer included the line: “The Wrap couldn’t carry Deadline’s jockstrap”), but the efforts have felt like warmed-over Finke. In what looks like an attempt to inject some Finke-style brashness into its reporting, Deadline announced the hiring of Anita Busch, an aggressive Hollywood reporter who’s been out of the business since 2004, when her life and career were derailed amid threats by the since-convicted private investigator Anthony Pellicano.

It’s equally uncertain, and much more interesting, what happens to a Deadline-less Finke. Her weekly box-office analysis is widely respected, and that’s something she can take with her. But the world in which Finke came to power is long gone. What was new ten years ago—the voice and instantaneousness of blogging—has become a given. What was then an open field is now crowded with competitors.

In our recent conversations, Finke swung from despondent to euphoric. She said she was exhausted. Her voice sounded strained. She said, starting to cry, that she is going blind; in January, she was diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy, and she attributes her deteriorating eyesight to the burdens of working for Penske. Her assistant, the daughter of her longtime housekeeper, had recently said, “You were so much happier when doing Deadline Hollywood Daily in the L.A. Weekly days” of the mid-aughts. “I said, ‘You know, you’re right.’ ” She was looking forward to being on her own again, just a girl and her blog. “I just think of myself, not to romanticize, sitting at two in the morning, chuckling to myself, writing what I consider to be the truth, and just having fun. There’s something so fantastic about having your own site and doing it all.”

She says she wants to leave the scoop-chasing micro-newsbreaks to others and return to the thing she did best: the big insider pieces, and “not being part of the Hollywood publicity machine.” She says she has roughly a dozen offers of various sorts of financial backing, which she has narrowed to three serious offers to buy nikkifinke.com, with her attached as the sole writer. She has a book deal, and has sold the film rights. Last week, she was weighing two possible designs for her site, one “sleek and cool,” the other red and black, which she was calling Pirate Nikki. “Like, Arggghhh, Nikki.”

Even after all that has happened, though, Finke still isn’t ready to deem her partnership with Penske definitively kaput. “I really can’t imagine not having Jay in my life,” Finke had said just a few weeks earlier. More recently she’d said: “This is as bad a relationship as I’ve experienced.” She seemed sad, when not angry, about the turn their relationship had taken, and it’s hard not to see the last few weeks as the grand culmination of a chaste romance between two people who were improbably well suited to each other.

Then, on November 18, she told me: “Never say never. It’s entirely possible that Jay and I make up, and he runs nikkifinke.com. Anything is possible.”

*This article originally appeared in the December 2, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.