In the catalogue accompanying Christopher WoolÔÇÖs impressive retrospective now at the Guggenheim, the artist Richard Prince writes of this artistÔÇÖs multiple uses of ÔÇ£spray-┬¡painted swirls ÔǪ transfer drips, splatters, puddles, and ÔÇÿby-the-byÔÇÖ patterns,ÔÇØ and how they ÔÇ£taught an old dog new tricks.ÔÇØ The ÔÇ£old dogÔÇØ here is painting; the ÔÇ£new tricksÔÇØ are the ways in which WoolÔÇÖs greasy-looking, commanding surfaces, the narrow formal confines he set for himself, and his ambiguous polycentric spaces create alchemical cyclotrons. WoolÔÇÖs paintings of blocky letters, words, and phrases; abstract graphic fields filled with erasures; and boxy geometries implausibly synthesize the gesturalism of mid-century ModernismÔÇönow out of style, semi-┬¡forbiddenÔÇöwith cooler art from the age of mechanical reproduction. Think of his paintings as places where WarholÔÇÖs disaster, flower, and Rorschach paintings meet PollockÔÇÖs and de KooningÔÇÖs, all done in black mucoid goo. The results have made Wool, 58, among the most influential mid-career American painters.

WoolÔÇÖs work can grate, be hard to like, easy to hate. And when itÔÇÖs hated, itÔÇÖs hated hard. HeÔÇÖs a risky subject for the Guggenheim, one that might alienate wide audiences and critics alike. Many of these blunt scribble-and-smear paintings can leave lay audiences shaking their heads at yet another art-star strutting his disaffected noir-ness. Moreover, the show is simultaneously too long and not comprehensive enough. I dig his gritty black-and-white pictures of New York, but there are just too many of them for most visitors to take. Yet thereÔÇÖs no pre-1987 painting hereÔÇöwork that would explain how Wool emerged in the years when painting was going through another one of its nervous breakdowns. So was his work. No matter: IÔÇÖm such a 30-year fan that I walked up the GuggenheimÔÇÖs ramp thinking IÔÇÖd take any one of these home.

Not everyone would. Brilliant critics, especially the male ones, have lambasted Wool. Dave Hickey deemed his work ÔÇ£trendy negativity ÔǪ academically palatable brand of designer-punk agitprop.ÔÇØ The L.A. TimesÔÇÖs Christopher Knight dismissed it as ÔÇ£banal,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£impoverished,ÔÇØ and ÔÇ£startlingly conservative.ÔÇØ LA WeeklyÔÇÖs Doug Harvey seethed that ÔÇ£shtick-crippledÔÇØ WoolÔÇÖs paintings are ÔÇ£pedantic crap.ÔÇØ The GuardianÔÇÖs Adrian Searle tweeted recently: ÔÇ£He. Is. Just. Not. That. Good.ÔÇØ These guys donÔÇÖt like that WoolÔÇÖs art isnÔÇÖt ÔÇ£beautifulÔÇØ in traditional painterly ways and isnÔÇÖt dryly conceptual or pop. I think it splits the difference and arrives at something electric and ┬¡generative. Just last week, my pal Peter ┬¡Schjeldahl came right out and wrote that he does ÔÇ£fondly wish ÔǪ for a champion whose art is richer in beauty and charm.ÔÇØ For me, WoolÔÇÖs work has a lot of both.

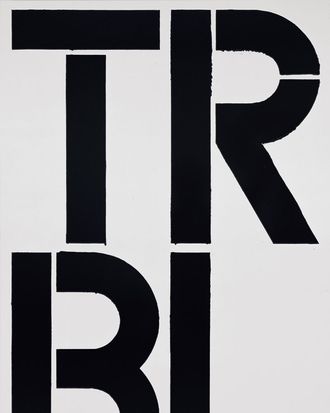

So be it if WoolÔÇÖs art is something some people cross the street to avoid. The show begins with a typically twisted bang in the gallery off the entry ramp. On your left is a large word painting in navy enamel on a stark white-aluminum ground. Like all of WoolÔÇÖs paintings, it looks like an abstract X-ray. Generic, stenciled, gridded-out letters run almost edge to edge. ThereÔÇÖs no punctuation; all the letters are the same size; everything forms an enormously long run-on sentence. Then it decays into babble, executing a nifty C├®zanne-ish trick: When you stop trying to read it straight, arrangements, orders, and compositions appear. (The writer Jim Lewis describes it this way: ÔÇ£When you multiply misunderstanding ÔǪ meaning emerges.ÔÇØ) Finally, you make out the first words of the painting: THE SHOW IS OVER. TheyÔÇÖre from Greil MarcusÔÇÖs classic punk-rock text, Lipstick Traces, and are a perfect metaphor for the artistic dilemma Wool, his in-between generation, and painting itself found themselves in, in the eighties. Starting an exhibition by saying THE SHOW IS OVERÔÇömuch as Apocalypse Now begins, with Jim Morrison singing ÔÇ£This is the endÔÇØÔÇöadds paradoxical layers.

As you make your way up the ramp, other paintings of single words like PLEASE, RIOT, and FOOL turn up, as do phrases like YOU MAKE ME and THE HARDER YOU LOOK. ItÔÇÖs like moving through the city and hearing it talk back to you: ÔÇ£Do not block driveway,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£No pets,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Valid I.D. required.ÔÇØ Glenn OÔÇÖBrien once called WoolÔÇÖs work ÔÇ£sign-painting with feedback,ÔÇØ and that feedback goes almost infinite in my favorite Wool paintingÔÇöthe one that quotes words never spoken, only seen, in Apocalypse Now: SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS. The moment I first saw this painting in 1988, I gleaned a different kind of border-to-border abstraction, the simple dense expression of complex thought. The painting became an epic three-line novel. The Guggenheim wisely decided not to show this magnum opus, presumably because its owner has chosen next week to sell it at ChristieÔÇÖs, where the estimate is $15 million to $20 million. Maybe the painting gets the last laugh, as WoolÔÇÖs own work often taunts such opportunists. The painting taunts such foul hysteria.

Higher up on the ramp, we move beyond word paintingsÔÇöthey are in the minority hereÔÇöand we instead see Wool continually recycling abstract gestures, motifs, marks, and meandering lines; exploring glutted matte surfaces, uneven blocked-out areas, fragmented overlaps of screened images, faint traces of Benday dots. There are works with repeating flowers. ThereÔÇÖs little all-out color. A few blocks of spattered yellow; a couple of paintings have sloshes of a rust-colored cinnamon. Some deep blues read as solid black. There are paintings that look like theyÔÇÖve been wiped down and almost blotted out. Other times, there are rolled-on areas of splotchy whites, stamped marks, oblong flecks. For me, Wool captures the ways New York looks, sounds, and smells in our time, much as Jackson PollockÔÇÖs drip paintings embody the cityÔÇÖs texture in the fifties. I see Wool creating new order out of all this chaos. I see little epiphanies and glean the same clashing, gritty, seemingly haphazard, abrasive, bludgeoning beauty that all of us who live in and love New York canÔÇÖt live without.

*This article originally appeared in the November 11, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.