Michael WilliamsÔÇÖs fourth show since 2007 at this painting-centric gallery gives electric evidence that his painterly promise has come to impressive fruition. In the two spacious galleries of the newly relocated Canada, I was stunned into something like a stupor by WilliamsÔÇÖs work. No matter how closely or long I looked at these eleven large colorful paintings, I could not gain a purchase on their surfaces. His new work delivers a sort of tranquilizer bullet to oneÔÇÖs ability to detect haptic presence. A viewer knows thereÔÇÖs paint on the canvas, and yet when one tries to focus on it through the multiple overlays of images and abstract fields, the paintings continually come into and then fall away from actually feeling physical. Philosopher Maurice Blanchot has written about such paradoxical ÔÇ£inaccessibilityÔÇØ as something being in ÔÇ£infinite pursuit of its own source.ÔÇØ I know that I felt like WilliamsÔÇÖs new paintings suspended me in an optic warp that kept me probing their processes and painterly source.

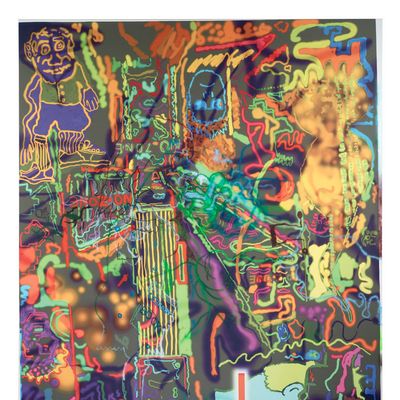

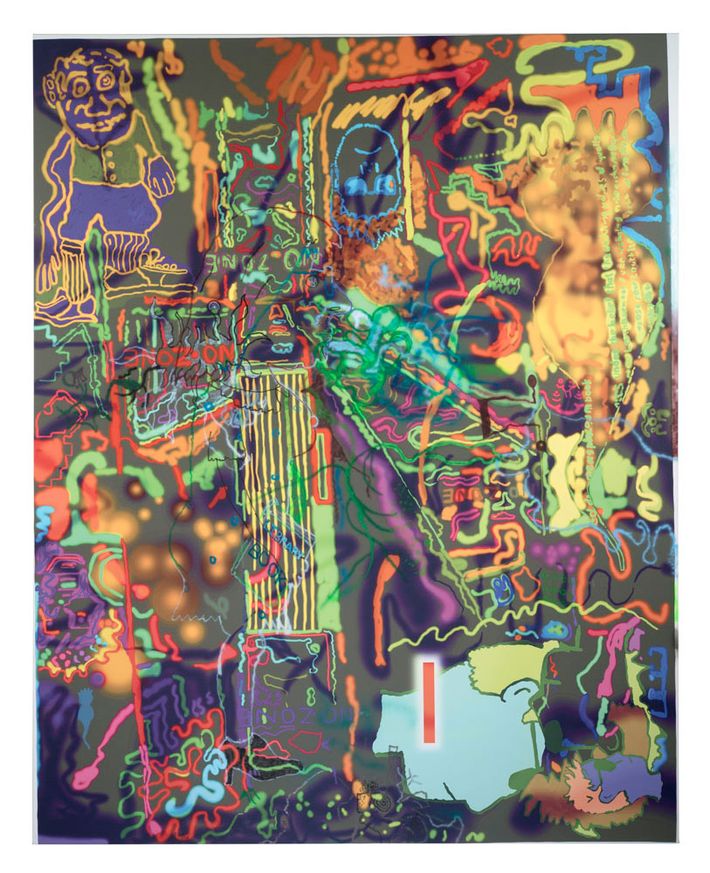

Eschewing the agglomerations of paint, glutted surfaces, and insistent comic imagery or all-over abstract patterning of his previous work, Williams appears to draw on a computer screen, print the image on canvas, stretch it, and then paint it here and there. The pigment seems to be applied very lightly with a spray gun, in what looks like flecks or stains of paint. You can perceive scratchily drawn lines, hazy shapes, cloudy overlays of mossy color. These hand-worked processes blend with the printed surface, and youÔÇÖre thrown back in that retinal warp where you canÔÇÖt quite make out where the surface is or how it works. I glean a strange new painterly topography.

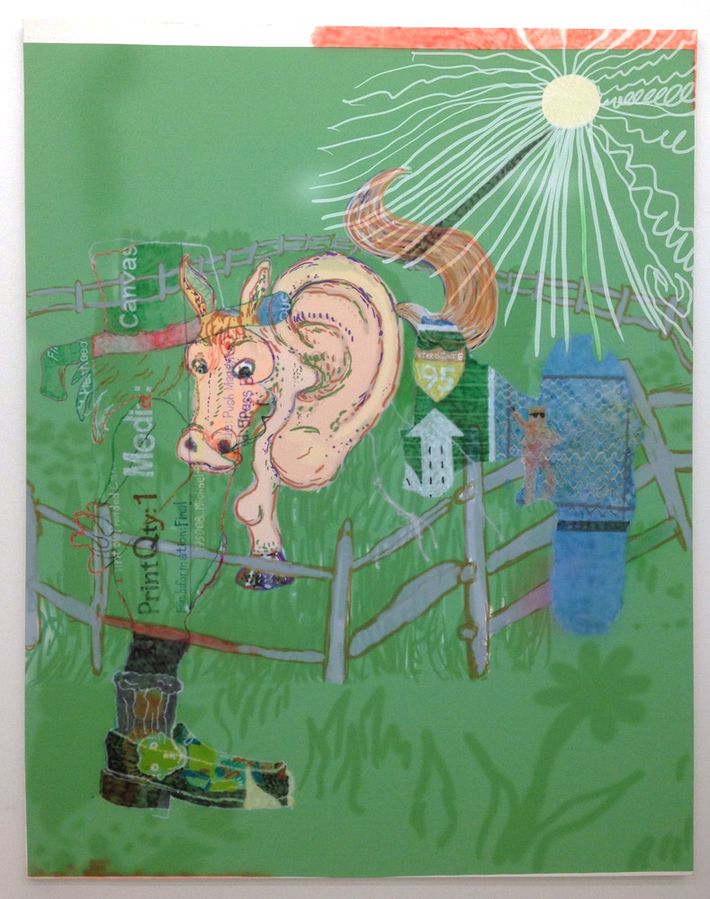

Though not every painting works, the whole show is good, and three stand out. Ikea Be Here Now (from 2013, like all the work on view) centers on a naked man in glasses standing in front of a house, a ladder behind him. Another nude figure, maybe a model holding some sort of page that the naked guy appears to be holding, is also present. I saw what looks like a sawhorse, possibly a carpenterÔÇÖs plane, another naked figure, and someone with a backpack. The high-keyed eye-popping Day-glo color is just this side of truly gaudy. In the crowded-to-the-point-of-blissful-confusion Honk If You DonÔÇÖt Exist, you might spot images, patterns, polka dots, stripes, clouds, and street signs. Soon, you give up trying to name what youÔÇÖre seeing, and then these aggressively pictorial works turn very abstract. It Came Out of My Paint Tube is actually ballsy enough to have a big Philip GustonÔÇôlike shoe smack in the middle, along with a cute cream-colored sun and a cow with an ear for a body. I think thereÔÇÖs perspective and illusionistic space in this cartoony thing, but that could all be me, trying to make sense of how itÔÇÖs organized.

His method of organization, in fact, is greatly enhanced by two more ingenious formal devices. The images and fields on the canvas are not quite squared to the edges of the paintings. The eye detects tilt, or something that seems off. It corrects for this, then goes back to the edge to check and finds that the correction was wrong, whereupon the whole painting pitches again. This back-and-forth balance activates the surfaces in extremely subtle ways. Then, once Williams has got you to the edges, thereÔÇÖs one last twist, maybe the most physical one. The sides of almost all of these canvases are dotted and marked with pings and incidents of paint. I saw them as little paintings in themselves but also as experiments, test thoughts, color ideas, different mixes of translucencies and transparencies. The paintings are also their own palettes and menus. In revealing his processes and failed experiments, the paintings avoid being overly cerebral, coy, or self-conscious.

All the paintings here create the same kind of visual hit as billboards, placards, brightly colored advertisements, or Internet images. In a number of them, the painterly incidents and cockeyed space canÔÇÖt overcome the cartoony drawing, funky bad-boy chaos, garishness, or the occasional plainness, and those are the paintings that donÔÇÖt entirely come off. In this show, Williams is evincing his familiar influences and visual kin, artists like Guston, Bonnard, Vuillard, Peter Saul, and R. Crumb, plus some Chicago Imagism and California funk. But in the most successful ones Williams adds the complexities of artists like Peter Doig, Carroll Dunham, and Sigmar Polke. Instead of trying to get between photography and painting, like Doig does, Williams looks to be getting between painting and the digital world, like Wade Guyton. The connections to Polke and Dunham come in the form of Williams freeing himself and allowing the painting to tell him what to do to it. (Remember that Polke memorably titled one of his paintings Higher Powers Command.) This freedom, with his shifting spaces, overcoded polycentric multilayered composition, and weird materiality, make WilliamsÔÇÖs new work stand out.

ÔÇ£Michael Williams: PaintingsÔÇØ is at Canada, 333 Broome Street, through December 8.