You’ve seen this couple face the cameras before: he, a politician stuttering his way through a canned apology for sexual misdeeds; she, standing silently, slightly behind him, her lips drawn tight in — what? — disapproval? Fury? Mortification? Or is it, as Bruce Norris’s new play, Domesticated, seems to suggest, a kind of triumph?

Make no mistake: This latest provocation from the author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning Clybourne Park is more than a gloss on Eliot and Silda Spitzer, the most obvious of many possible models for his Bill and Judy Pulver. Norris is in it for something much bigger than a takedown of political hypocrisy. Bill — who is not just a Secretary of Something but also a women’s-health crusader and, oh why not, a former gynecologist — did more than patronize prostitutes. That would hardly be news. What Bill did, accidentally or not, was cause a prostitute to fall and strike her head on a bedframe while yanking a “paddle” or (in the prosecutor’s preferred locution) “erotic plaything” from his hand. In any case, “Naughty Gabrielle,” as she advertised herself, ended up in a coma, to be tended by her mother “from West Bumfuck” and subjected to the avenging mercy of Oprah.

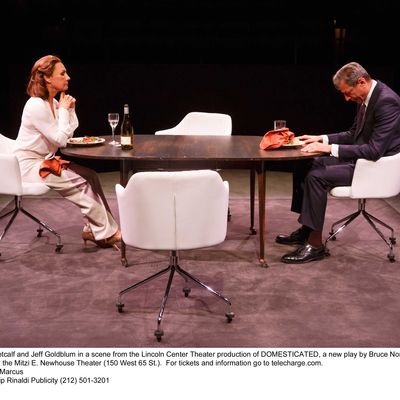

What happens to Bill and Judy — Jeff Goldblum and Laurie Metcalf, in brilliant, unimpeachable performances — is both hilarious and awful. Judy writes a book about Bill’s use of prostitutes, which fails to earn enough money to cover Naughty Gabrielle’s settlement. Bill finds, after resigning his post, that he cannot return to gynecology. (Women aren’t exactly lining up to get Pap smears from him.) When new revelations strain the marriage further, Judy removes Bill from her health insurance just as he injures his eye in an altercation with a transsexual. It’s around this point that you realize you are watching a Passion Play, albeit one in which the Christ is a clueless, pervy liar and his tormentors are all female. Indeed, all 27 other characters (played by ten actors) are women, including, we are told, the transsexual. Norris seems to have included her to demonstrate our culture’s presumption that even a biological male — Robin de Jesús, giving big Dominican sass — would have unquestionable cause to hate men. Bill does too, if you believe him: “For a man to want compassion from women,” he says, “is like a Nazi asking sympathy from a roomful of Jews.” Oh yes, Norris goes there.

Part of what’s hilarious about Domesticated is the way the playwright not only goes there, but stacks the deck on arrival. It might not be fair at the poker table, but when done this artfully it makes for marvelous theater. In Clybourne Park, a series of nastier and nastier (and funnier and funnier) jokes kept Norris’s bitter vision of race aloft for two hours. Here, he seems to be pushing the absurdities to see just how far they can go without exploding his argument. The answer is: farther than you want to believe. Which is another way of saying that his absurdities are not so absurd. Bill and Judy’s marriage, though more ruthlessly anatomized, is perhaps closer to the norm than normals admit. Even before the incident, it was perched atop rotten compromises and willful blindnesses that could not be inspected and would prove useless in a storm. (Their relationship began in college, while Judy was having an affair with the married chairman of the Ethical Studies department.) Is it any wonder that their daughters are messes? The 17-year-old is a whip-smart but vile-tongued virago; the 13-year-old, adopted from Cambodia, is asthmatic, lactose-intolerant, possibly bulimic, and seemingly mute. “Does she even speak English?” Bill wonders at one point.

Yet it’s this girl, Cassidy, played with deadpan verve by an eighth-grader named Misha Seo, who gives Domesticated its framework and announces its apparently dispassionate theme: the collapse of sexual dimorphism among humans. In what is probably meant to represent her middle-school science project (though it’s very advanced, even for Brearley) she narrates a series of interstitial video clips suggesting the imminent extinction of the human male. Until recently, that once-great gender resembled the male ring-necked pheasant (she explains) in its unquestioned primacy; by her final example, man is reduced to the ignominious condition of the bone-eating snot-flower, whose “dwarf male is no more than microscopic in size, living in colonies within the female’s genital sac, and never developing beyond the larval stage.” Or as Bill puts it with characteristic sensitivity: “Coupla years from now you won’t need us at all. Except maybe to lift something for you.”

Case closed on men — or is it actually closed on women? This is where Norris’s brilliant technique may be obscuring something dodgy. Sure, Bill is awful, but he’s just one man, frequently misunderstood. We are given access to some of his justifiable confusions and better intents. But of those 27 female characters, no more than three or four, the ones less characterized, are within a standard deviation of nice. Judy you forgive because she’s been through the wringer, though Norris makes her a bit more vicious than seems likely. (Having intercourse with Bill, she helpfully explains, was “like squirting paint stripper up my vagina.”) But their lawyer (Mia Barron, glossy and commanding) is basically a classic TV bitch. The transsexual (who is given to hapless mispronunciations like “his-directory”) taunts Bill for what she assumes is his “tiny little dick” — ironic, under the circumstances. Even a victim of horrific sexual torture, whose can-you-top-this tale of woe is at first played for laughs, is soon turned into a caricature of anti-American intolerance.

I’m not diagnosing Norris, as the harpies diagnose Bill, with “you just don’t get it” disease. Domesticated is a play, not a manifesto. But with its biological framework and Big Picture perspective, it does sometimes seem like a treatise. Near the end, Bill offers the topic sentence: “In the last 50 years, we’ve reached a remarkable turning point in history where, in a precise inversion of how we treated you … anything a woman could possibly want is universally construed as good, and all of a man’s desires — for all intents and purposes — are bad.” But Norris is too smart a dramatist to leave it so bald. He connects all the dots to an emotional truth: At the moment his wife gives birth, a man realizes that the “big prize for his participation” is that she now “loves something else more than you.”

So call it a rigged fight: rigged for your pleasure! Certainly the director, Anna D. Shapiro, a longtime Norris expert*, has staged the play with enormous punch. The Newhouse on this occasion is configured in the round, so it already feels like an arena when the audience arrives. And in a brilliant feat of counterintuitive pacing, Shapiro enhances the feeling of comic dread by blowing through the viciousness at a brisk clip while hovering over the few touching moments with respect and tenderness. The technical departments, too, are up to Lincoln Center Theater’s usual level of excellence, with special kudos to John Gromada for his exceptionally vivid and subtle sound design, and to Jennifer von Mayrhauser for her Sildariffic pantsuits.

But all this excellence produced, in me at least, as I laughed my way home, a mote of resistance. If men have lost the evolutionary battle so miserably and definitively, why is Norris’s play on the subject such a winner?

Domesticated is at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater through January 5.

* This post has been corrected; it originally misstated that Shapiro had directed Clybourne Park.