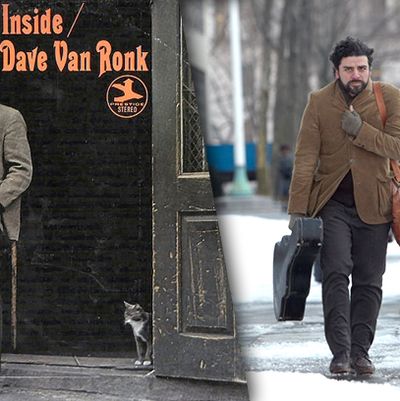

The Coen brothers have been very open about the various influences behind their new film, Inside Llewyn Davis. Most prominent, the filmÔÇÖs titular character is inspired by legendary folk-musician Dave Van Ronk. The Coens mined Van RonkÔÇÖs memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, for details, but ÔÇö despite some minor similarities (his album cover for Inside Dave Van Ronk is identical to LlewynÔÇÖs, and inspired the filmÔÇÖs name) ÔÇö Van RonkÔÇÖs personality and career were very different from those of Llewyn. To find out what else in the Coen brothersÔÇÖ world rang true or false, we consulted two people who lived through the real thing ÔÇö Terri Thal, Van RonkÔÇÖs first wife, and Sylvia Topp, wife of Tuli Kupferberg, author, poet. and lead singer of political-rock band the Fugs.

Both women lived in Greenwich Village during the time the filmÔÇÖs events take place, and both were deeply entrenched in the eraÔÇÖs cultural movements ÔÇö Thal worked as a booking manager for many folk artists, including Van Ronk, Bob Dylan, the Holy Modal Rounders, and Maggie and Terre Roche, and Topp co-published books with Kupferberg and counted Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac among those in her circle. HereÔÇÖs what they had to say about the filmÔÇÖs fidelity to the scene they knew so well.

Creative Liberties

While the Coen brothers mined Van RonkÔÇÖs memoir for general details ÔÇö Llewyn Davis (played by Oscar Isaac) is the polar opposite of the real folk singer. Unlike the sullen, selfish, outburst-prone Llewyn, ÔÇ£David was brilliant, funny, talkative, and charming,ÔÇØ said Thal. The two met at a party on the Upper West Side, and ran into each other again in 1957 at Caf├® Figaro, one of Greenwich VillageÔÇÖs infamous hangouts of the day. She was impressed when he insisted on chaperoning her home to Brooklyn ÔÇö a real feat at the time. In 1961, Van Ronk married Thal and the two lived in an apartment on Waverly Place. ÔÇ£He was just the nicest guy,ÔÇØ said Topp, who recalled once sharing a cab with Van Ronk and Kupferberg. ÔÇ£He had such presence ÔÇö he was a big guy with a really low voice. He had quite a reputation ÔǪ every single person in the Village in the early sixties would absolutely know Dave Van RonkÔÇÖs name. He was not unknown, like Llewyn.ÔÇØ

The CoensÔÇÖ dismal depiction of 1961 Greenwich Village and its players couldnÔÇÖt be further from the truth. ÔÇ£The performers reflect absolutely nobody I knew in the folk-music world,ÔÇØ said Thal. ÔÇ£The world that they live in is a depressing, unhappy place, and we lived in a fun, musically vibrant, intellectually interesting world. People were competitive only in the sense that they were trying to be heard ÔÇö they werenÔÇÖt out to score above anybody else.ÔÇØ

And as for Jim and Jean (the musical couple ÔÇö and friends of Llewyn ÔÇö played by Justin Timberlake and Carey Mulligan, who are loosely based on Jim Glover and Jean Ray), Thal said, ÔÇ£They did very innocuous music. We had absolutely nothing to do with them.ÔÇØ The filmÔÇÖs U.S. Army member and traveling singer Troy Nelson (Stark Sands) is roughly based on folk singer Tom Paxton (Nelson even sings one of PaxtonÔÇÖs biggest hits, ÔÇ£The Last Thing on My Mind.ÔÇØ)

What It Really Looked Like

Of a scene in the film in which Llewyn visits his record label in search of money with which to buy a winter coat, Thal says, ÔÇ£They did take that from DaveÔÇÖs book. Moe Asch owned Folkways Records, which was a very small, obscure company that issued some American folk, English folk, and┬áÔÇö I guess you would call it ethnic music from all over. It was a wonderful catalog. He couldnÔÇÖt make very much money on it, and no one got royalties. That story is real, about the coat.ÔÇØ

Llewyns journey in the film is one filled with frustration and the possibility of being forced to leave the scene. His life is made harder by increasing competition, including musicians from out of town. The Coens nod at this by including a timid autoharp-playing female performer visiting from the South and a quartet of white cable-knit sweater-clad Irish singers. In the late fifties, the folk singers who were around were almost all from New York, Thal explained. As the coffee houses opened, people from elsewhere came in and started becoming successful. Many of the locals who lived in New York  had families, they went back to college, they became teachers. They did other things. Many of the people who made it, and Im not talking about people who became as successful as Bob [Dylan] or Peter, Paul, and Mary  most of those people were from elsewhere.

ThereÔÇÖs also a moment when John GoodmanÔÇÖs Roland Turner, a jazz musician, exclaims to Llewyn, ÔÇ£Folk singer? I thought you said you were a musician!ÔÇØ The sentiment rang true for Topp, who found it to be a succinct way of describing their separate musical worlds at the time. ÔÇ£Jazz musicians kind of looked down on folk musicians,ÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£They felt you didnÔÇÖt have to be a great musician to play a guitar and sing a song.ÔÇØ

The Gaslight

The club where most of the filmÔÇÖs performances take place is the popular MacDougal Street music venue the Gaslight (which was in operation from 1958 to 1971), but the cinematic version of the interior is hardly reflective of the real thing. Thal pointed out that the Gaslight didnÔÇÖt have a bar (almost no clubs at the time did), while the CoensÔÇÖ version had, ÔÇ£A clean shiny bar! No! Nothing in the Gaslight was clean and shiny!ÔÇØ She was also surprised to see the locationÔÇÖs infamous ÔÇ£Tiffany-style lampsÔÇØ omitted from the movieÔÇÖs set piece.

ÔÇ£On MacDougal Street, there isnÔÇÖt anywhere that can be that big and open ÔÇö and the Gaslight was in a basement,ÔÇØ said Topp. ÔÇ£It was long and skinny, like the tenement buildings on that block, so there wasnÔÇÖt enough room to have anything quite as grand as what the Coens depicted. It had a very warm, cozy atmosphere, despite being a bit more squished than in the movie. There were usually more people sitting around the tables, because so many people wanted in.ÔÇØ The club was correctly alluded to as a ÔÇ£basket house,ÔÇØ referring to the typical practice at some Greenwich Village establishments that booked unpaid artists, where funds were raised by passing a basket through the audience to collect donations at the end of musical sets.

The Early Days of Dylan

In the CoensÔÇÖ depiction, Bob Dylan (briefly seen at filmÔÇÖs end) arrives on the scene in polished, recognizable style. The relationship between Van Ronk and then-unknown young Dylan was much more of a mentor-mentee scenario ÔÇö Dylan was promising, but rough around the edges at first. Thal recalled meeting Dylan after Dave heard him sing and raved about him. ÔÇ£We became very good personal friends,ÔÇØ Thal said. Dylan even slept on their couch from time to time.

From Dave, Bob ÔÇ£learned attitude, he learned a lot of guitar work, he learned a lot of songs, a lot of arrangements,ÔÇØ said Thal, who went on to manage Dylan for a year before he signed with Albert Grossman (who earns what may be the most truthful depiction in the film, in the form of Chicago club Gate of Horn owner Bud Grossman, played by F. Murray Abraham). When Grossman approached Dylan with a management request, ÔÇ£I very cheerfully said, ÔÇÿOh, how wonderful! He can do so much more for you than I can!ÔÇÖÔÇØ remembered Thal. ÔÇ£And then we parted with a handshake, professionally.ÔÇØ

Greenwich Village

Early-sixties downtown New York City was a hotbed of creativity and community ÔÇö though the different groups tended to stick to their own hangouts. ÔÇ£There were the poets and the artists, the jazz musicians, and the folk artists,ÔÇØ said Topp. ÔÇ£They were pretty separate.ÔÇØ

Their motivations were less disparate, though. ÔÇ£The sarcasm about the people who werenÔÇÖt artists in the CoensÔÇÖ film, that rang pretty true,ÔÇØ said Topp. ÔÇ£Artists tended to feel superior, and everybody else was just wasting their time and their talent or they were selling out. Being a struggling artist was something to be very proud of. Even so, there werenÔÇÖt that many down, angry people like Llewyn was ÔÇö you would laugh at the middle-class people rather than curse them or feel sorry for them. They were living these shallow lives and didnÔÇÖt realize what they were missing, thatÔÇÖs how you would look at them.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£People wanted to be heard,ÔÇØ said Thal. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs not that they wanted to get rich ÔÇö nobody really conceived of it. To Dave and me, the idea of becoming a star was impossible and not even desirable. He lived his music. And so did a lot of the other people in the very early sixties. They researched it, they worked on it, they arranged it, they rearranged it.ÔÇØ

And though Inside Llewyn Davis cinematographer Bruno DelbonnelÔÇÖs hazy, desaturated vision of the world is beautiful paired with the CoensÔÇÖ overcast, wintry set pieces and contentious players, it painted a cold, unfriendly picture to Topp and Thal. ÔÇ£It was so joyful in New York City at the time,ÔÇØ said Topp. ÔÇ£If you walked up and down MacDougal Street, everybody was talking to anyone, very open. There was none of this feeling that, ÔÇÿOh, maybe somebody wants something out of me.ÔÇÖ If you saw someone who looked interesting, you would just talk to them! It was so much easier back then. It was a very open, creative, joyous time.ÔÇØ