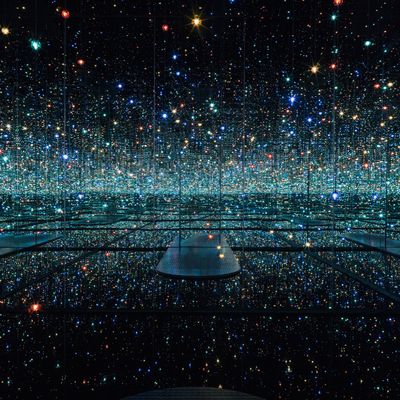

People love being part of something a lot of other people are part of. They love the weird madness and ecstasy of crowds. Preferably crowds of strangers, crowds that turn into subcultures on the spot, where being part of something is their central reason for being. ItÔÇÖs primitive, tribal. (Witness the whitest flash mob since hockey: SantaCon.) These days, art loves crowds too. The Museum of Modern ArtÔÇÖs techno-showy Rain Room and the GuggenheimÔÇÖs blah, mall-like James Turrell light show saw huge lines for admission. Lately, these lines have appeared at galleries, too. Since November 6, when it opened, there have been long lines outside David Zwirner Gallery at the windy tip of far West 19th Street, everyone waiting to spend 45 seconds in Yayoi KusamaÔÇÖs Infinity Mirrored Room ÔÇö The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away. (It closes this Saturday.) This booth-size room is dark except for 75 colored LEDs that surge, pulse, and are mirrored into infinity. Once inside the gallery, often after waiting hours in the rain and snow, people are asked to don booties like those you might wear in a quarantine unit. Then, when their moment comes, theyÔÇÖre admitted by gallery staff one or two at a time. ThatÔÇÖs it.

Ive long been a lover of all things Kusama  even the recent wild, multicolored, almost Aboriginal work that even her fans dont cotton to. Her net paintings of the late fifties and early sixties  almost monochromes of interwoven lines with ridges and rumples, with arrays and multitudes  go beyond Abstract Expressionism, look Pop before Pop, and point through minimalism to post-minimalism a decade before the latter even got started. Donald Judd was an ardent Kusama supporter, and owned her works. Of her own work Kusama wrote, My nets grew beyond myself and beyond the canvases  They began to cover the walls, the ceiling, and finally the whole universe. In other words, her world and work is hallucinatory and cosmic. Thats where this and other Infinity Rooms come in. After making numerous net paintings, Kusama covered walls, ceilings, furniture, people, and whatnot with dots and nets; she made performances with naked people having sex in these net sets. Eventually she made the Infinity Room.

I love that lots of people want to see it. Still, I couldnÔÇÖt get over the sight of everyone waiting for hours in the rain and snow. An art-critic house call to the line was in order.

On Saturday, I arrived in a blizzard. Outside Zwirner, the entire length of West 19th was a line of people, cowering in the storm, waiting. I didnÔÇÖt recognize anyone in line. I began talking to people, saying I was an art critic and was curious about a few things. I asked if theyÔÇÖd ever been to this gallery or any Chelsea gallery before. Almost all confirmed that this was their maiden voyage, although most had walked the High Line. Then I told them all that two of the other Zwirner Gallery locations, not 40 feet away, are open to anyone who wants to see KusamaÔÇÖs great new paintings. I told them that inside the Zwirner door, in the other direction, thereÔÇÖs another Infinity Room with no wait whatsoever. Instead of being lit with 75 LED bulbs, this one is dark and filled with wormy uncircumcised phallic shapes on the floor and ceiling that change psychedelic colors and are similarly multiplied by the mirrors. Then I told them the Whitney Museum owns an even larger Infinity Room, and that itÔÇÖs often on view. I even showed them all my iPhone pictures of the Zwirner Infinity Room that they were killing a half day to see for 45 seconds. I finished with ÔÇ£The roomÔÇÖs cool, but itÔÇÖs not worth this kind of wait. Really.ÔÇØ Everyone I spoke to looked at me like I was some cracked geezer, politely said he or she was happy waiting in line, thanked me, and threw me a last look that let me know that I was a walking buzzkill. So much for the critic as public servant.