“Nobody goes through life unscathed, and I think if you write about those things, you’re going to touch people.”

That’s one of many simple yet moving observations by Stephen Sondheim, the subject of the HBO documentary Six by Sondheim, which debuts tonight (on a Monday, appropriately — a night that Broadway is traditionally dark). One of its executive producers is my New York Magazine colleague Frank Rich — who wrote about Sondheim here — and so of course I wrestled with whether to say anything about it at all, perhaps worried that people would think I was somehow in the bag for it, as the saying goes.

But as I watched the screener again for the third time last night, a couple of countering thoughts occurred to me. One is that this is one of the best movies about the artistic process I’ve seen — a film that can engross and illuminate even if you know nothing of Sondheim, except that he wrote Send In the Clowns and the lyrics to West Side Story and that mediocre Dick Tracy number that Madonna performed at the 1991 Oscars. It’s about Sondheim, yes, but more than that, it’s an exploration of where art comes from (a mysterious wedding of inspiration, biography, and craft) that just happens to use Stephen Sondheim as its subject and example and guide. The other thought was that Sondheim’s work has probably meant more to me over the years than any other theater artist, and I’m certainly not alone in that sentiment, and that I’d therefore probably be substantially in the bag for it anyway, as long as it was in focus with audible sound and had a lot of Sondheim songs in it. So you can take all that for whatever it’s worth, along with my belief that this film is, beyond its merit as a smart, compassionate, and ultimately moving celebration of Sondheim, a terrific example of filmmaking craft: equal parts biography, explanatory text, puzzle, and celebration.

As the title suggests, the movie is broken into six parts, each keyed into a Sondheim tune: “Something’s Coming,” “Opening Doors,” “Send in the Clowns,” “I’m Still Here,” “Being Alive,” and “Sunday.” Each is performed at full- or nearly full length. Some of these numbers are taken from preexisting TV or documentary film clips (Dean Jones’s performance of “Being Alive” from Company comes from D.A. Pennebaker’s fantastic 1971 documentary about the recording of the original Broadway cast album). Others are original, self-contained short films commissioned by HBO (Audra MacDonald singing “Clowns” in what looks like a backstage area filled with source lighting; Jarvis Cocker, under the direction of Todd Haynes, singing “I’m Still Here” to an audience of women of different ages). Woven around those performances is a series of mini-lectures by Sondheim in teacher-mentor mode, talking about the career or personal genesis of each tune, the commercial imperatives he was under as he wrote it (come up a showstopper for Ethel Merman in Gypsy; make you care about Tony in West Side Story; etc), and the problems each posed in terms of songcraft and how he solved them.

The documentary’s director and co-executive producer James Lapine, who has directed a number of Sondheim productions for the stage, adheres closely to certain principles that Sondheim outlines in interviews. One is that, as any performer will tell you, entertainers need to try to get in and get out, and not get sucked into too many digressions or enamored of lovely curlicues that don’t accomplish the piece’s stated goal. To that end, even though Six by Sondheim could have run three hours and few Sondheim fans would’ve complained, it’s a fleet-footed 87 minutes, yet it feels longer in a good way. You look at the clock at the end and think, Really? Can that be right?

The film is also edited, by Miky Wolf, in the spirit of another of Sondheim’s observations: that in order to be a good lyricist, one must be able to see words not just as signifiers of meaning but as collections of letters that create certain sonic or rhythmic effects all their own. On-camera, Sondheim talks a fair bit about games, puzzles, anagrams, and the like — at one point recalling how he once walked under a sign advertising the then-new photographic process Cinerama and immediately recognized it as an anagram for American — and how the ultimate purpose of all art lies in “making order out of chaos,” or attempting to. In that spirit, Six by Sondheim makes narrative order from the chaos of Sondheim’s life and imagination. It does this through the intricate arrangement of individual bits of information that are analogous to the puzzle pieces that Sondheim cites in his own examples; I’m talking about Sondheim’s own words, and the shots that either picture Sondheim saying those words or that illuminate their ideas.

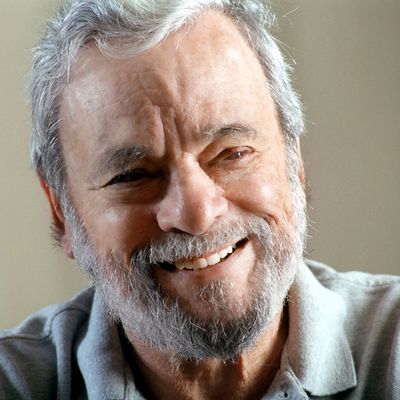

There are plenty of Sondheim observations to choose from. The man’s been giving interviews on-camera for six decades. Lapine and Wolf jump between old, gray Sondheim, woolly headed and goat-herder-bearded middle-aged Sondheim, and clean-scrubbed young Sondheim, within the space of one anecdote. Some cuts happen during the pause where a comma would go if you were reading a transcript. It’s so seamless that you don’t immediately notice how clever it is. This, too, is Sondheimian — the acrobatically dazzling lyrical invention that somehow feels like a natural extension of everyday speech or thought. “It’s a form of showing off,” he says at one point, “but also a form of sharing.” (I can’t imagine how the filmmakers winnowed down the immense amount of archival material they must’ve had to work with; I’m picturing somebody sifting through a Matterhorn of pearls, selecting ones of similar shape and size, and discarding the rest.)

As Sondheim talks about the work, he also talks about himself: his journey through the American musical theater, his relationship to his mentors, peers, successors, interpreters, critics, backers, and audiences. The explanatory or pedagogical aspect of the documentary is front-and-center, but it’s that other aspect — the biographical aspect — that makes this documentary so rich, partly because Sondheim is a frank, warm, and giving camera subject, but also because there is no discernible separation between “craft” and “biography.” We can see how one feeds or drives the other, simply by hearing Sondheim speak and seeing his work performed. We hear of how Sondheim’s father was an absent presence, and how his mother was unspeakably cold to him, at one point telling him (in a letter prior to undergoing surgery) that her greatest regret was giving birth to him. We hear of how Oscar Hammerstein II was probably his closest thing to a healthy parental figure, tutoring the talented young Sondheim, making himself available as a friend and sounding board and, on his deathbed, describing Sondheim as “my friend and teacher.” We learn how much teaching means to Sondheim — he calls it “the sacred profession,” warns the interviewer that he’ll probably cry as he talks about it, and then does. In an ABC News clip, he tells Diane Sawyer that he regrets never becoming a biological father, but that “art is the other way of having children.”

It all ties together in a dazzling moment late in the film that I won’t describe in detail here, because it’s just wonderful. Suffice to say that it’s the best cameo by a great American artist since Jim Henson cast Orson Welles, the consummate struggling artist-outsider, as the boss of a studio in 1979’s The Muppet Movie. In this one scene, Sondheim is simultaneously an artist caricaturing the profit motive, a businessman appreciating that same motive, an old naysayer pouring cold water on young people’s pie-in-the-sky dreams, a practical-minded instructor telling us that it’s possible to reach a popular audience without compromising one’s creative values, and, most of all, a performer strutting his stuff. “As a writer, I think what I am is an actor,” Sondheim tells the filmmakers. “I’m an actor when I’m writing songs.”

We are on some level aware that the order that this movie superimposes on Sondheim’s life story equals the order that Sondheim himself imposes as he tells the same stories over and over again. That’s another part of this movie’s excellence: the way it illustrates our tendency to make stories of our lives, so that the nonsensical appears to make sense, and so that it all seems to be leading somewhere. The order created in Six by Sondheim isn’t really order, but “order” — which is what we know we crave when we seek out art in the first place; an illusory sense of wholeness, a feeling that it is in fact possible to make sense of life. Six by Sondheim obviously knows all this — and it nearly tips its hand in a graphic image of puzzle pieces gradually connecting to form an image of Sondheim speaking to us, as well as in several stunning pointillistic images keyed into Sunday in the Park With George — yet it confidently and delightfully refrains from trumpeting its knowledge. For the most part, Six by Sondheim’s awareness of its own design is unobtrusively embedded beneath every moment of the film, like a refrain buried so deep in a musical’s score that the ear doesn’t register it until the final curtain.